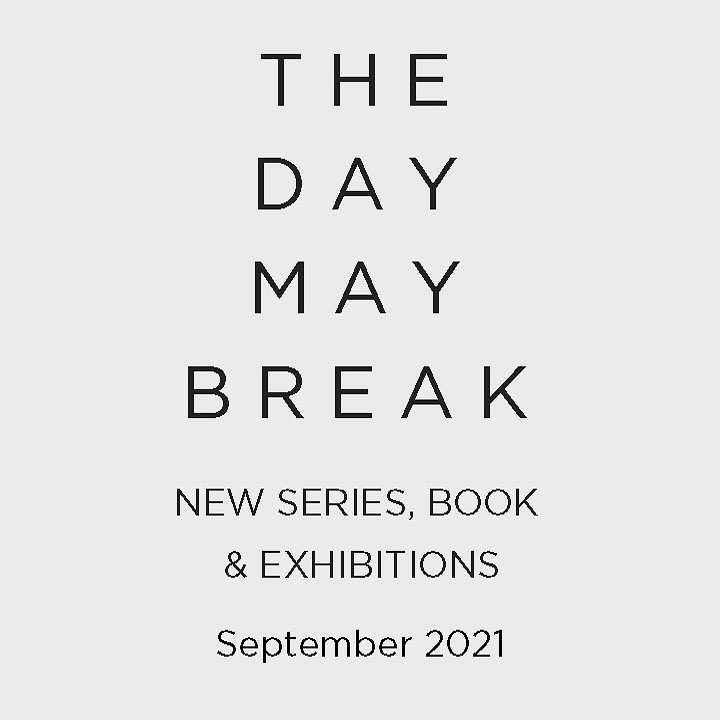

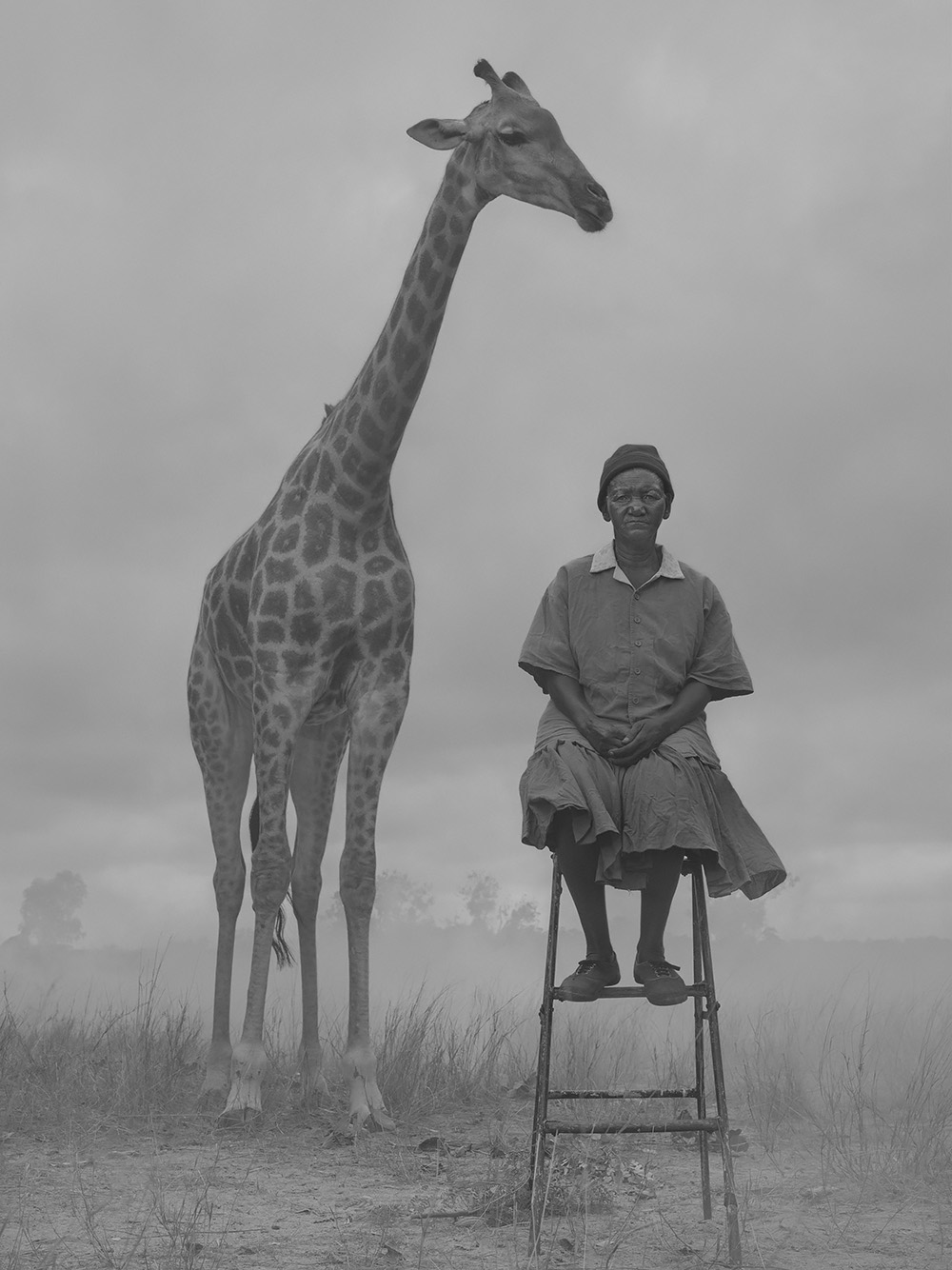

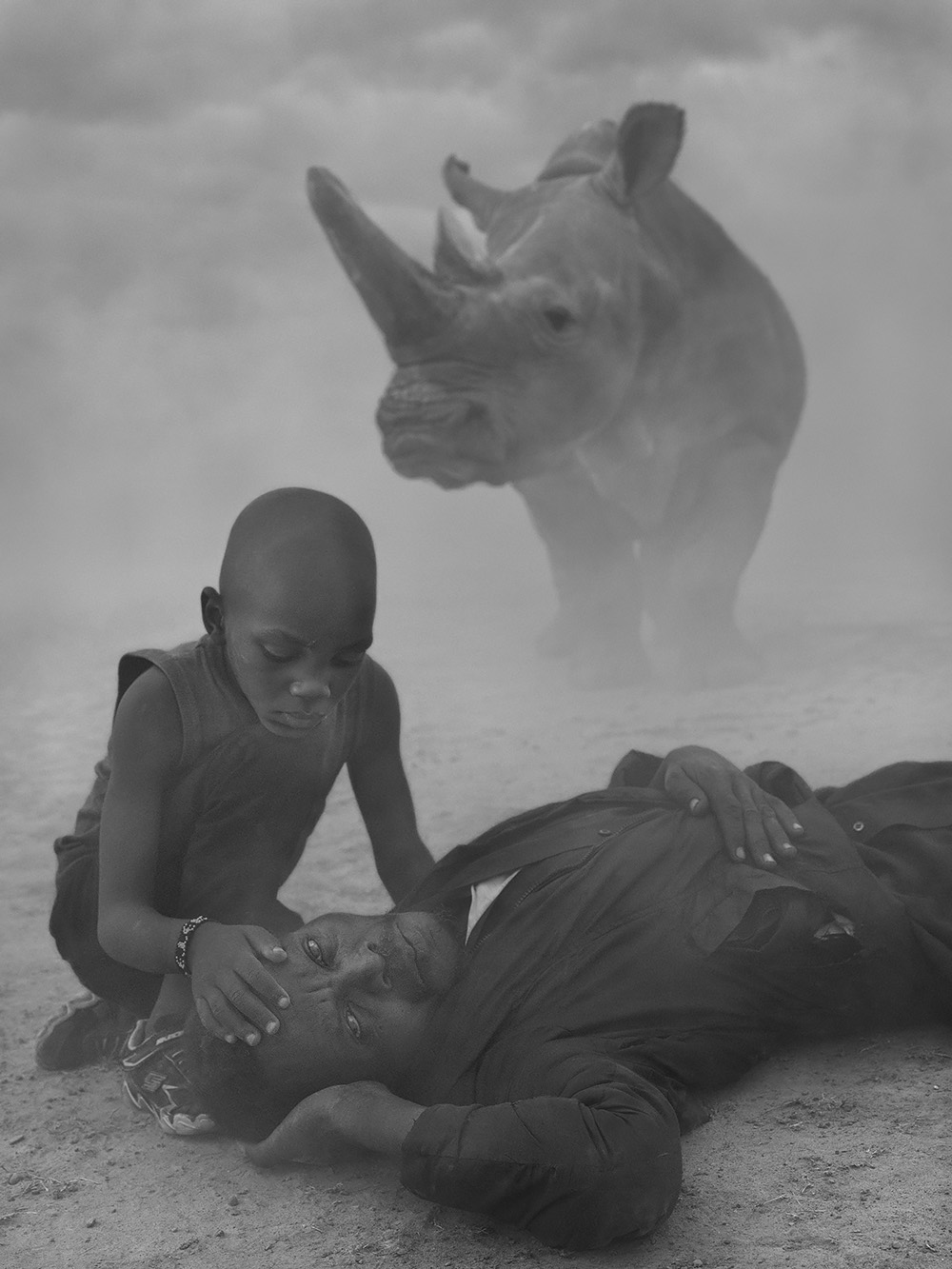

Photographed in Zimbabwe and Kenya in late 2020,

The Day May Break is the first part of a global series by acclaimed photographer

Nick Brandt, portraying people and animals that have been impacted by environmental degradation and destruction. The people in these photographs have all been badly affected by climate change—some displaced by cyclones that destroyed their homes, others such as farmers displaced and impoverished by years-long droughts.

Photographed at five sanctuaries/conservancies, the animals are almost all long-term rescues, victims of everything from the poaching of their parents to habitat destruction and poisoning. These animals can never be released back into the wild. As a result, they are habituated, and it was safe for human strangers to be close to them and photographed in the same frame at the same time.

We wanted to know how such an ambitious project came to life and Nick Brandt kindly answered our questions:

Regina, Jack, Levi and Diesel, Zimbabwe 2020 © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

All About Photo: Such projects require a lot of preparation. How did your idea for this new series come about?

Nick Brandt: Prior to COVID, I had a far more elaborate idea that dealt with climate change, for shooting in California only. However, due to COVID, that became impractical, even though it's where I live. But also, the fog I had planned to use as smoke in the photographs took on a whole new layer of symbolism with COVID - this feeling, for me, of living in a kind of limbo, of having no idea how things would turn out. Of course, this also applies to our current environmental situation on the planet - how will things turn out? Will we and our fellow creatures survive this coming apocalypse?

So I felt that I could make a global series, connecting both humans and animals impacted by environmental degradation and climate change, and that the fog also became symbolic of a once recognizable world now fading from view.

How did it become a reality?

Once I get an idea, I'm obsessed. I find that have no choice but to execute it, no matter how terrifying the financial implications of doing it may be.

Fatuma, Ali & Bupa, Kenya 2020 © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

In 2020 the world was at a standstill with the covid19 pandemic how did you manage to travel to Zimbabwe and Kenya? Why did you choose these two countries?

I started in Zimbabwe and Kenya because of everywhere in the world that I am planning to shoot, I could actually get into both countries in the last few months of 2020. The timing was fortunate, between surges.

Of course, there was a level of familiarity with Kenya that helped. And critically, both countries had sanctuaries and conservancies with habituated rescued animals that would safely allow human strangers to be close to them.

What extra precautions or difficulties did you have to overcome because of the pandemic?

I brought a large supply of 95 and surgical masks with me for everyone involved over the two month shoot. Any time someone got in a vehicle, they had to wear a 95. Fortunately no-one got sick. Everyone was much more mature about wearing masks there than some of the crybabies in America, etc.

Your previous series had in common the idea that the world as we know it is disappearing because of human activity, but you denounce the effects of development through the struggle of animals, why is this project different?

This project is the first that also addresses climate change in addition to biodiversity and habitat loss. It's the first in which people are literally the focus of the photographs.

Alice, Stanley and Najin, Kenya 2020 © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

Why did you choose this title 'The Day May Break'?

In spite of their loss, the people and mails in these photographs are survivors.

And there-in this survival through such extreme hardships-there lies possibility and hope.

So . . . The Day May Break . . . and the world may shatter.

Or perhaps . . . The Day May Break . . . and the dawn still come.

Humanity's choice. Our choice.

All the people featured in the project have been directly impacted by climate change, how did you meet them?

For a couple of months before arriving, we had researchers out looking for people whose lives had been dramatically impacted by the effects of climate change.

You have always been an advocate for the preservation of wildlife including with the creation of Big Life Foundation, but why did it seem important to you in this new project about climate change to include stories about people?

Climate change will eventually negatively affect every human on the planet, but most of all, most immediately, the rural poor. Of course the rural poor are also affected by biodiversity loss and environmental degradation, but climate change adds a whole new horror into our lives.

What stories from Jack, Regina, Helen and the others touched you the most? Why?

There are three who lost two / both of their children - swept away in floods, never to be seen again: Kuda from Zimbabwe, and Robert and Nyaguthii from Kenya. How they had the strength to go on, I don't know. I would have just crumbled.

Kuda and Sky II, Zimbabwe 2020 © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

There is always a strong visual aesthetic in your work but in this one in particular the fog and the light bulb in the middle of nowhere are extremely poetic. Why did you choose this angle to talk about such a difficult subject?

As mentioned, the fog creates a kind of limbo, a once-recognizable world now fading from view. The fog also renders the animals almost a dream, or a memory of what the people once experienced in their lives. It is also an echo of the suffocating smoke from the wildfires, driven by climate change, devastating so much of the planet.

As for the lightbulbs, I chose props that represented the barest bones for living - a chair, a table, a bed. And for light, a single bare lightbulb.

Why is it so important to you as an artist to be a witness of the world's fate? As an individual?

I don't have a choice. It eats me up and obsesses me. I need to do what I can with the skills I have to express my feelings about what is unfolding. And perhaps others may also be affected along the way.

Do you believe there is hope to save our planet, its inhabitants and ecosystem?

Big weary sigh. I have never felt more despairing than this year. It feels like the whole planet is on fire. But I would not be doing this work if I felt there was no hope. These people and animals in the photos are survivors of traumatic events in their lives, but they are still alive. And where there is still life, there is hope. We must, must, must, fight to preserve what remains. As I say over and over, don't be angry and passive, be angry and active.

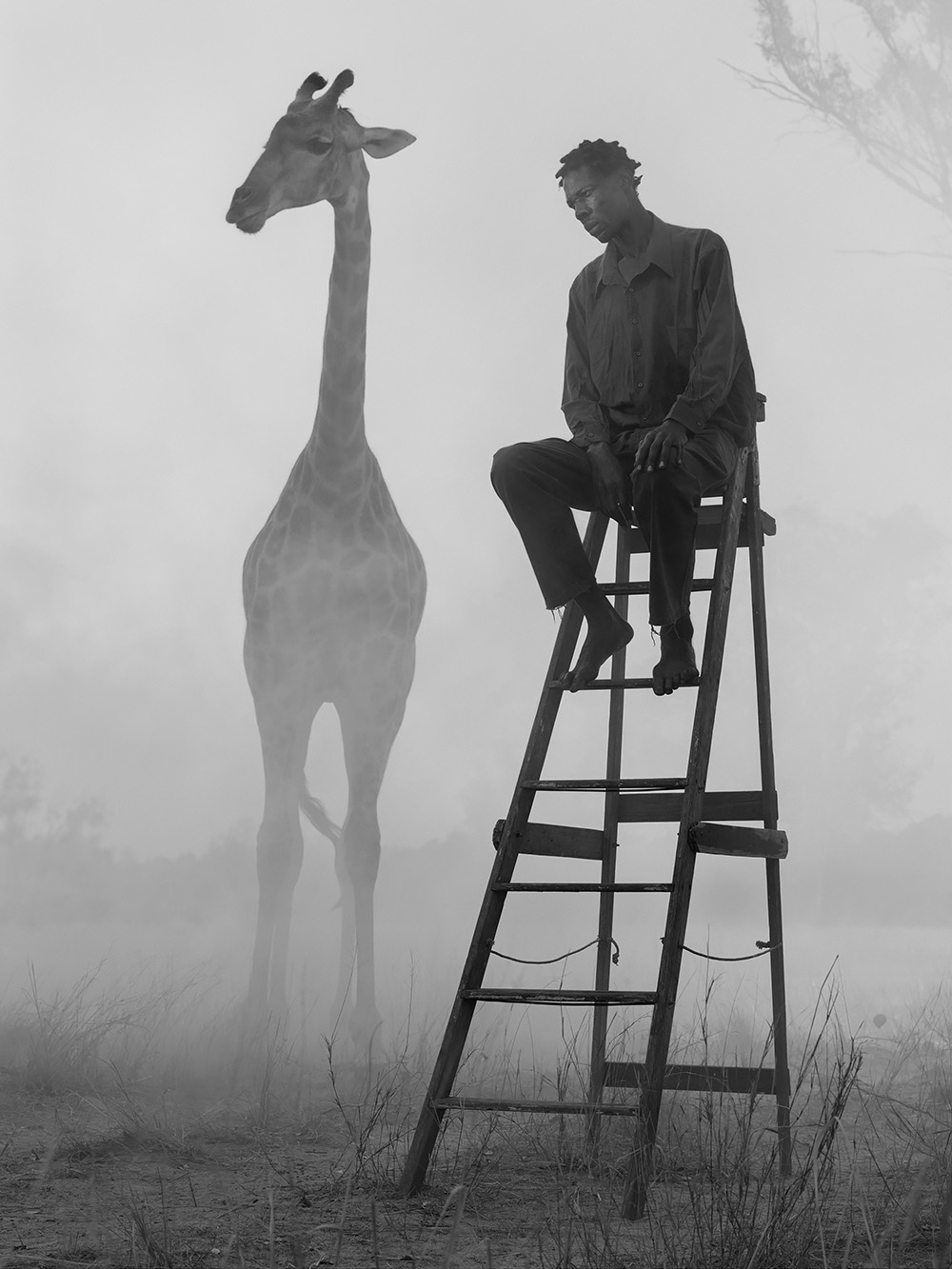

Making of The Day May Break © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

Can you describe the process by which you made the images?

The shoots were very spontaneous. The animals were wonderfully relaxed thanks to their keepers, and so the people in the photos also were. The fog was created by fog machines on location, which was by far the most challenging part of the shoot, as we were often working in baking hot, extremely dry, sunny and windy conditions, so the fog would almost immediately dissipate. As a result, many of the photos were taken in the 30 minutes before sunrise, and after sunset. Shooting in sunlight was as always for me, not an option.

But I worked very loosely, swapping out people until it felt like the right combination of animals and people, and seeing what serendipity would unfold. For me it was like photographic jazz.

While most of the images are in B&W, why are some in colors?

Yes almost all the images are in black and white, and that was the intention of the project - a foggy, monochromatic world, but for just four images, those worked better in color, most specifically the photograph of Sofia and her father and Fatu, the rhino, because of the vivid colors of her blue dress and gold embroidery, emphasizing the impression of her as a young queen sitting on her wooden throne, while her father stands by her like her courtier.

The young girls in the seizes are deliberately projected as the strongest subjects - it wasn't directing on my part, they just conveyed that impression. And to generalize, young people are and must be the hope for the future, and most of all women, with (usually) their greater empathy. Let's hope that an African Greta Thunberg emerges very soon.

Sofia, Mohammed and Fatu, Zimbabwe 2020 © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

What equipment did you use?

Because the fog was ever-shifting, from frame to frame, I had to shoot digital to be able to review what I had shot at the end of each session. I used a Fujifilm GFX100 medium format camera.

The Day May Break is part of a global series, have you already shot the one? When do you plan on releasing it?

Not yet. I hope to be able to start work in other countries early in 2022. Of course, between COVID and everything else, anything could change...

Harriet and people in fog, Zimbabwe 2020 © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

Richard and Grace, Zimbabwe 2020 © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

About Nick Brandt:

Nick Brandt (b. 1964, London) studied painting and film at St. Martin's School of Art, London. He moved to California in 1992. In 1995, Brandt became aware of the terrible devastation of the landscape and fauna of East Africa, leading him to make his seminal trilogy

On This Earth (2005),

A Shadow Falls (2009),

Across the Ravaged Land (2013). In 2010, Brandt co-founded

Big Life Foundation which works to protect the animals and ecosystem of a large area of Kenya and Tanzania. The escalating destruction of the natural world in Africa, and its impact on both the wild animals and the rural poor inspired the artist to create the pivotal series

Inherit the Dust (2016) and

This Empty World (2019). Brandt has exhibited worldwide, including solo exhibitions at Fotografiska, Stockholm; Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow; and the National Museum of Finland, Helsinki. The artist lives and works in California.

Nick Brandt's Website

Nick Brandt on Instagram

All About Nick Brandt

Book: The Day May Break

The Day May Break at the Fahey/Klein Gallery

James and Fatu, Kenya 2020 © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

Halima, Abdul and Frida, Kenya 2020 © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

Helen and Sky, Zimbabwe 2020 © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

James, Peter and Najin, Kenya 2020 © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

Patrick and Flamingos, Zimbabwe 2020 © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

Richard and Sky, Zimbabwe 2020 © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery

Teresa and Najin, Kenya 2020 © Nick Brandt, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery