I spent over three months traveling across Ukraine covering different parts of this war seeing the damage

from as many perspectives as I could. Nothing felt more sobering than my time in Bucha and Irpin.

Everyday on the 30 minute drive back to Kyiv I would stare at my hands holding my camera. I would

remind myself how interconnected each victim of this war is and how integral their life and death are to

any narrative around this conflict.

Rewind to my first trip to Kyiv. I arrived by car in the middle of March, after the Irpin Bridge had been

destroyed and Russians had started occupying the outskirts of the Kyiv region with hopes of a second

attempt to capture the capital. Bucha, Irpin, and Hostomel were the last line of defense protecting Kyiv

from becoming a battleground. Shelling could be seen and heard miles into the distance throughout most

days. The frontline felt dubious, changing each hour. Several journalists had already been killed trying to

report what was happening in contested areas. The war was getting more intense and many were dying

at the hands of the invasion but it was hard to get close enough to cover the facts.

On the last day of March, news broke that Russian soldiers had been forced to retreat and were quickly

abandoning the cities surrounding Kyiv they had been occupying since February. The now destroyed

towns like Bucha, Irpin, Hostomel and Bordoyanka were finally liberated.

Navigating the previously occupied neighborhoods was uncertain. The scenes that were left in the

liberated towns surrounding the capital were nothing I could’ve prepared for. Mines were scattered

everywhere so even driving on a desolate road was done with extreme caution. Beautiful homes had

been robbed and vandalized with empty liquor bottles scattered on the floors. Bedrooms had been

ransacked in search of valuable items and kitchens sat like a horror film rotting in filth- seemingly burned

from the inside. Family cars and vans with the word ''дети'' (children) in Russian were destroyed by

bullets left in the driveways and on roads marked with the letter V.

Bordoyonka was the most stark example of the structural damage of war; the streets resembled the

aftermath of a hurricane, earthquake, or both. There wasn’t a business left unmarked, and rescue workers

were diving through the debris of highrise residential buildings. Symbols of the once thriving

adminstrative center of the region was oddly juxtaposed against the infinity of destruction.

In Irpin and Bucha, death permeated the air and lined the streets- a family with two young children lay by

a park, tortured and burned. Their presence was evidence of something more sinister than just a war. It

was an unnecessary evil- a genocide and if it had happened here it was happening all over the country.

Soldiers' bodies were also being uncovered while others were being returned home after dying in battle.

Families would gather for the funerals for fallen servicemen multiple times a day, as volunteers at the

local cemeteries were digging plot after plot. Mothers wept watching fellow soldiers and family members

ceremoniously tossed dirt onto the newly lowered caskets. Photographing these moments can be

particularly challenging because the pain is so palpable. I would catch myself holding my breath

inadvertently because even the sound of my own breathing seemed obtrusive.

Behind the town Church of Andrew the Apostle, in Bucha, hundreds of bodies were pulled from a mass

grave while more were extracted from the rubble of destroyed buildings and homes. Volunteers worked

laborious hours to help collect bodies in backyards, nursing homes, parks, and residential buildings. I

watched through my lens as the innocent and helpless were placed tenderly in bag after bag numbered

and recorded for investigation. In some cases, family members had died of natural causes and were

buried by their loved ones but most of the exhumed bodies showed signs of war crimes.

After almost two weeks, the last bodies were being lifted from behind the Church of Andrew. The Church’s

priest prayed while police and investigators oversaw the final exhumation and volunteers started loading

bodies onto trucks to cemeteries and morgues. The front lawn of the Church was packed with anxious

family members who hadn’t heard from their loved ones since the start of the war. Some knew their loved

ones had been buried in the mass grave but others weren’t sure and had shown up to try and identify a

corpse. After 33 days of Russian occupation, an estimated 458 bodies were recovered in Bucha

according to municipal records.

It feels important to highlight the life that exists in occupied regions outside of the war- the humanity of

the Ukranian people that continued to out weigh this ongoing conflict. The families and communities that

came together, grieved together and started to rebuild together showed a glimpse of a Ukraine before the

invasion.

I checked in with myself and my role as a documentarian during this time quite frequently. At times there

was a lot of media documenting one moment of tragedy and I tried to make photos with justice for Ukraine

in mind. It was one of those situations where being human and being impartial could not coexist. The

days were long and continuously heartbreaking but finally the world was bearing witness to unimaginable

horrors and war crimes happening behind enemy lines.

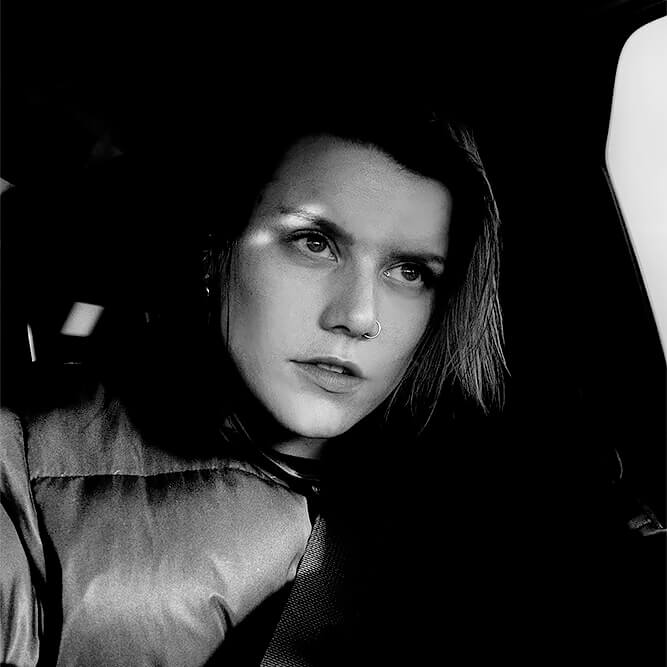

Svet Jacqueline

Svet Jacqueline grew up In Baltimore, Maryland. She earned a Bachelor of Science in Photography from the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University in 2014. She moved to Los Angeles, California in 2016 to work on freelance projects with Sony Entertainment, Apple, and other editorial clients. In 2020, she documented the uprising of the Black Lives Matter movement and published her first book, 100 days of Protest, 2021. Last year, she split her time in Los Angeles, Mexico, and Texas documenting migration at the border and the cycle of poverty on Skid Row where her work won first place in the International Photography Awards and NPPA Best of Photojournalism 2022. Her recent efforts focus on the humanitarian impact of displacement in conflict zones and Russia's war on Ukraine. She has published with Göteborgs-Posten, Teen Vogue, The Jewish Times, and HBO. focus on the humanitarian impact of displacement in conflict zones and Russia's war on Ukraine. In her free time, she trains for marathons, cooks, and volunteers with local nonprofits to feed underfunded communities and support public art programs.

www.svetjacqueline.com

@___svetj

All about Svet Jacqueline