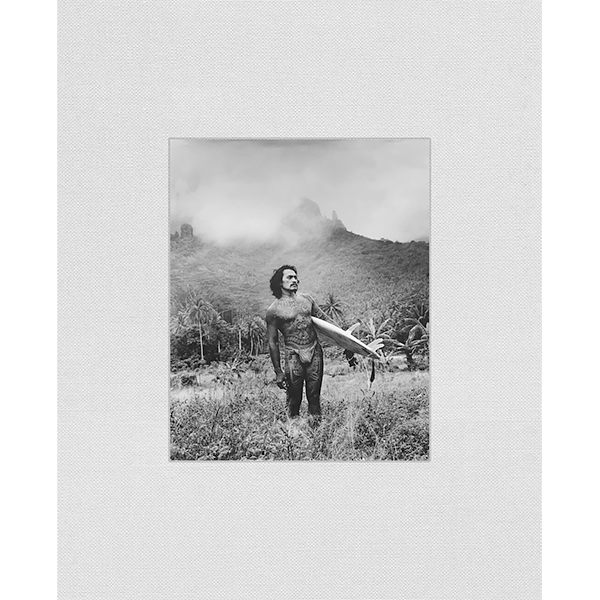

Patrick Cariou's first overview of his famed portraits of marginalized cultures, in acclaimed photobooks such as

Surfers and

Yes Rasta

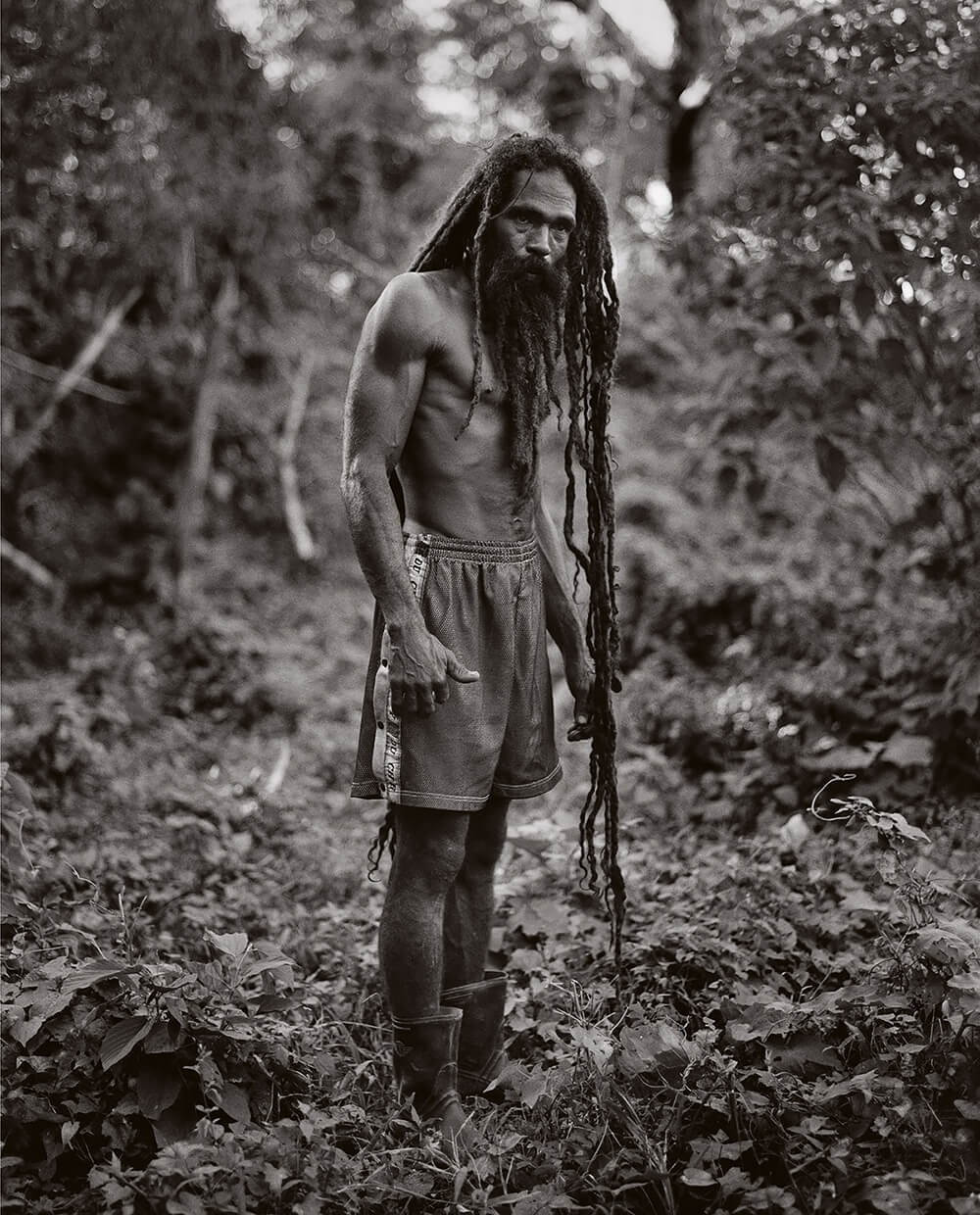

For more than 25 years, French photographer Patrick Cariou has traveled to places around the globe, documenting people living on the fringes of society. Whether photographing surfers, gypsies, Rastafarians or the rude boys of Kingston, Cariou celebrates those who meet the struggles of life with honor, dignity and joy. Bringing together works from his groundbreaking monographs including Surfers, Yes Rasta, Trenchtown Love and Gypsies,

Patrick Cariou: Works 1985–2005 (published by

Damiani) takes us on a scenic journey around the world, offering an intimate and captivating look at cultures that distance themselves from the blessings and curses of modernity.

All About Photo: Your forthcoming, self-titled book is a culmination of all of your previous photobooks. All are focused on certain subcultures from around the world, surfers, Rastafarians, and gypsies for example. What drew you to photograph these groups?

Patrick Cariou: It was never an ambition of mine to photograph these so-called ''subcultures''. I don't want to sound mystic, but it came as a series of visions. With Surfers, I can tell you, I was quite impressed with a group of people who consciously choose to play with the ocean, instead of pursuing a career.In all of these groups there's an element of aesthetics as well.

When it comes to Rasta, I've always been drawn to Jamaica from a young age and nothing serious had been done about Rastafarians. It's also a question of style. I find Rastafarians extremely stylish. With the gypsies, yes, it was a more secretive society, but it just happened very naturally, one step after the other. I can understand why people think I focused on subcultures, but it wasn't really my main interest.

Your work is anthropological. Was it difficult to gain entry into these subcultures in order to photograph them?

Surfers were very easy, you know. I would just travel around the different towns and stay there long enough to meet people. Jamaica was really complicated, because it was dangerous as a white man with a camera. Back then I was living in New York and nobody thought I would make it alive. You run into shit in Jamaica. It was very difficult, but after traveling for years you develop these skills and a certain personality that allows easier access.

Gypsies were different depending on what part of the world. With the French gypsies, for example, I already had some connections there. They are big gangsters so I really needed that connection, some families I wouldn't have dare to ask.

The main problem was when I went back to where everything started in Rajasthan and India. The language was a struggle and it was complicated to find someone who could translate. Within the project you could have different problems, depending on the condition these people were living in. The key world in all of this is patience.

Your photographs also draw focus on the importance of preserving native cultures. How has travel factored into your work and how did you choose who and where to shoot?

You do a lot of research before you start. You get all the books you can and then depending on the opportunities you can change your mind. It's a free set of mind in order to be receptive to the opportunities that come to you.

Can you share a great story from the images in each of these books:

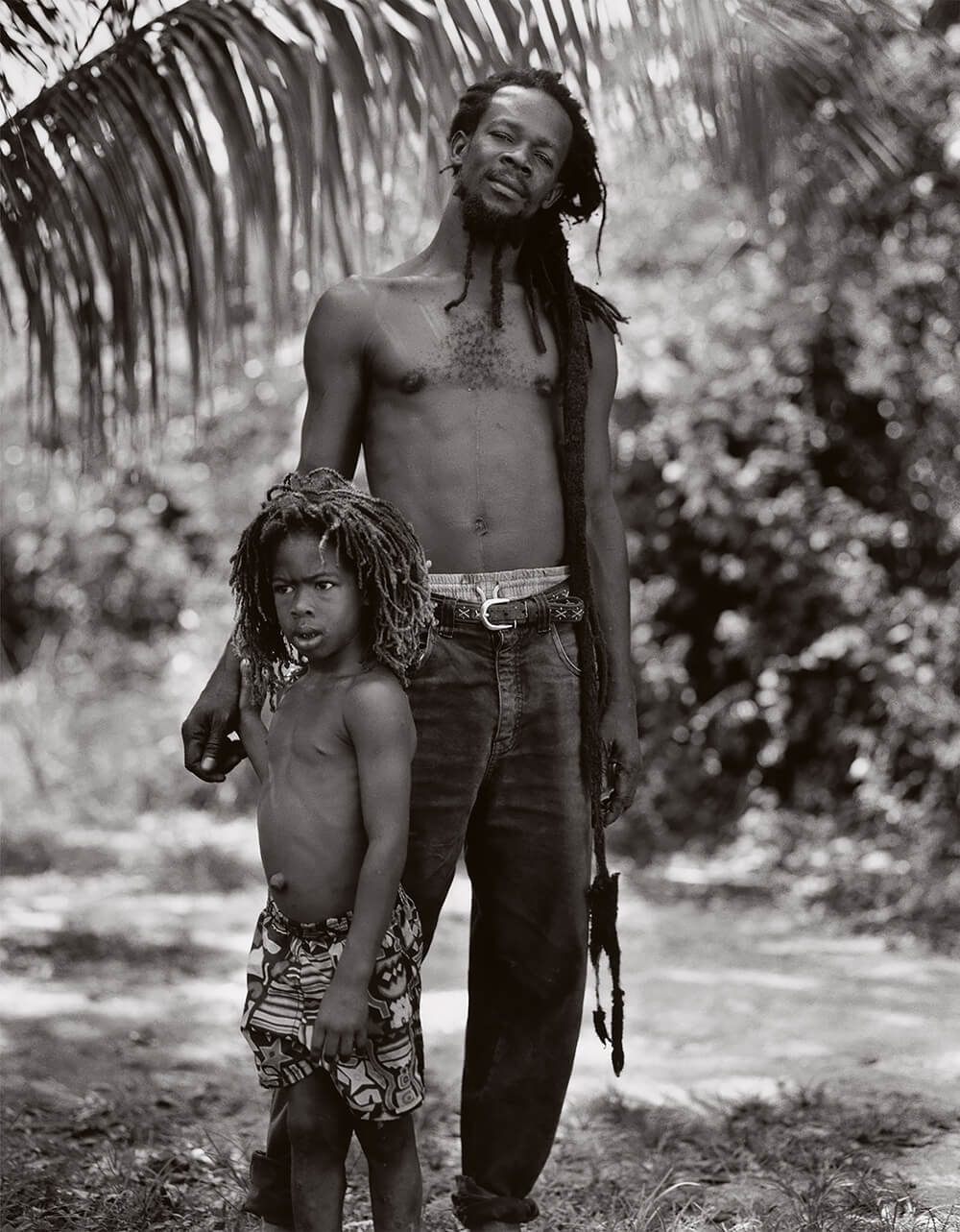

In

Yes, Rasta there is an image of a Man and Boy with Dreads. This is one of the first pictures I ever took of the project. At that time I didn't know it was extremely rare for children to have dreads. First, they don't allow kids with dreads in school in Jamaica. Also, because Rastafarian is an adult choice. He hung out with his father for ten years and when he was 12 he chose to become a rude boy.

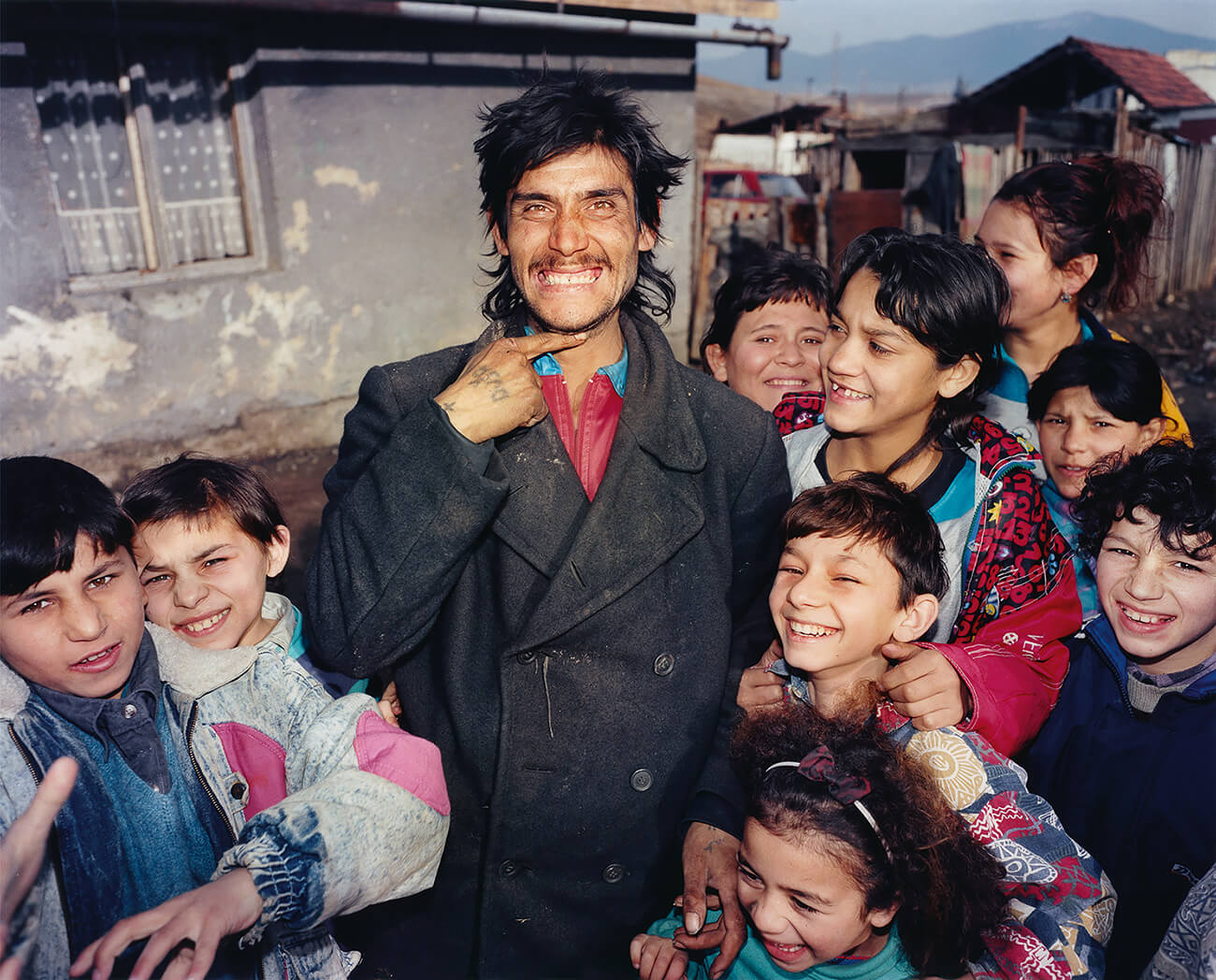

In

Gypsies, the cover of the book is a guy in the picture is telling me: ''if you take my picture. I'm going to cut your throat''. That's why all the kids are laughing around him.

In

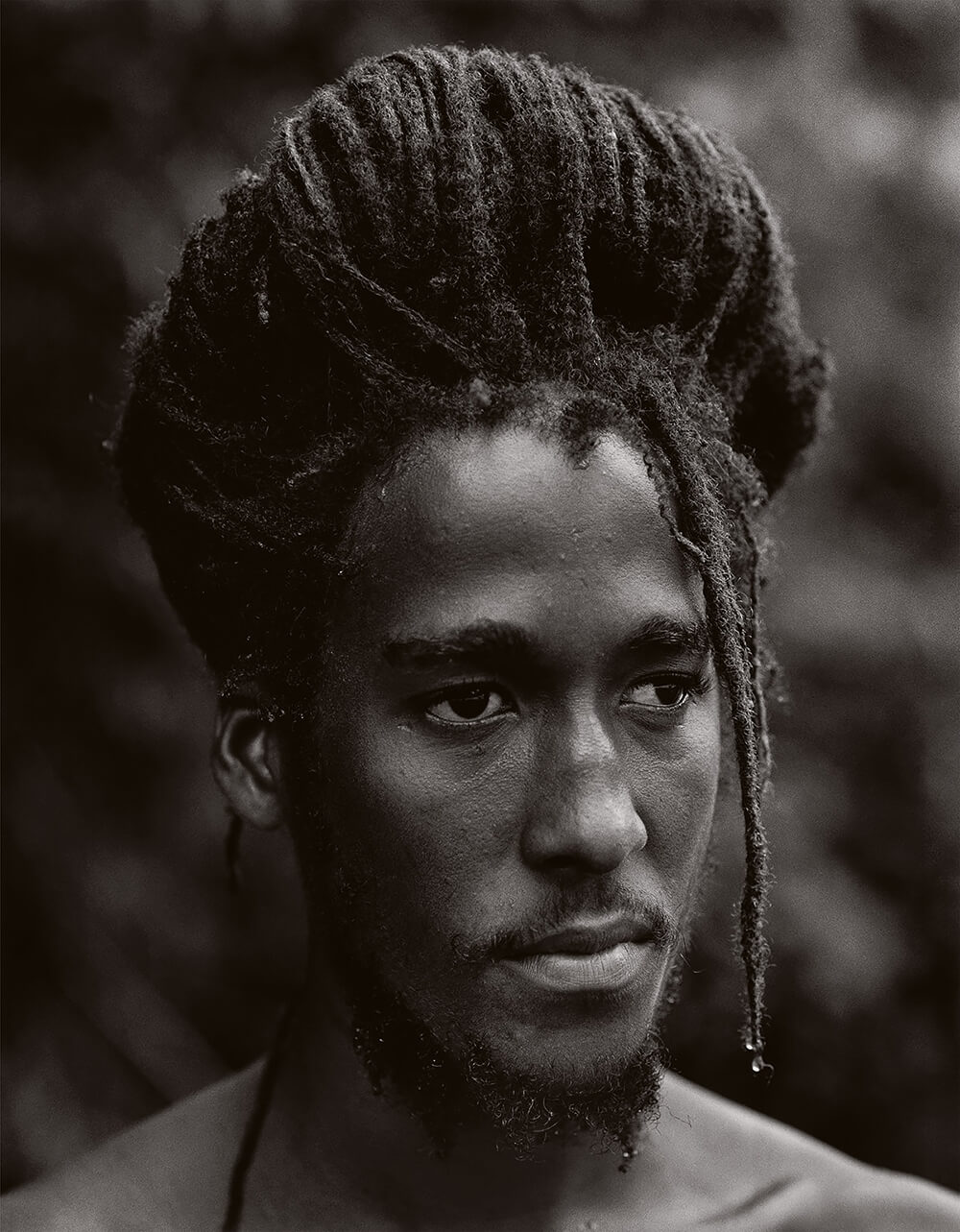

Trenchtown Love, when I started working on my Jamaican project, I wanted to do a book on Jamaican gangsters. I got shot at with an automatic weapon when I started, and gave up the project. Then one day out of pure luck, my friend who is of Jamaican origin was having lunch with the ''Don'' of Trenchtown, it was his first time out of Jamaica and he was visiting his cousin in NYC who left 25 years ago. The Jamaican restaurant was close to my house, so I brought him a

YES RASTA book and told him I'd like to do one about Trenchtown. To me, it's one of the most important ghettos in the world. That's where Bob Marley came from and grew up, that's where reggae music was born.

It took me months to get the guts to take the picture of a ''mean-looking'' guy. The ''Don'' had made some phone calls for me and two days later they were waiting for me in Jamaica so everything was cool. I really wanted to take his picture because of his look and energy. It took me months of motivation to get the guts to go talk to him.

With the culmination of all of your work in this one title, is there a plan to continue any of these projects or is this a ''closing the chapter'' book? What's next for Patrick Cariou?

I've been working for the past few years on landscapes and cityscapes with an 8x10 camera. I might change my might but I believe I'm done with portraits. I decided to drastically change and start something completely new.