In a world saturated with images, documentary photography remains a potent and indispensable form of visual storytelling. This genre of photography, which seeks to capture and communicate real-life stories and events, has continuously evolved and adapted to the ever-changing dynamics of contemporary society. Documenting life, society, and the world's various phenomena, it serves as a vital tool for social commentary, journalism, and art.

The essence of documentary photography lies in its power to freeze moments in time, preserving a visual history that connects us to the past and informs our understanding of the present. The camera lens becomes a witness to reality, capturing the essence of people, places, and events in a way that words often struggle to. This unique ability to convey the world's complexities, emotions, and narratives is what has sustained the relevance of documentary photography today.

Before delving into the heart of the matter, we want to clarify that in this article, we have blended documentary photography and photojournalism. Documentary photography typically involves more extended projects with intricate narratives, whereas photojournalism primarily focuses on covering breaking news stories. However, there is a considerable degree of overlap between these two approaches.

A Brief History of Documentary Photography

Documentary photography, a genre deeply intertwined with the evolution of photography itself, has a rich and storied history. Its roots can be traced back to the early days of the medium when pioneers aimed to capture the world around them in a truthful and unfiltered manner. Over the years, it has evolved into a powerful means of storytelling, social commentary, and documentation of human history. To understand the history of documentary photography is to delve into the visual record of our past, replete with images that bear witness to our shared human experience.

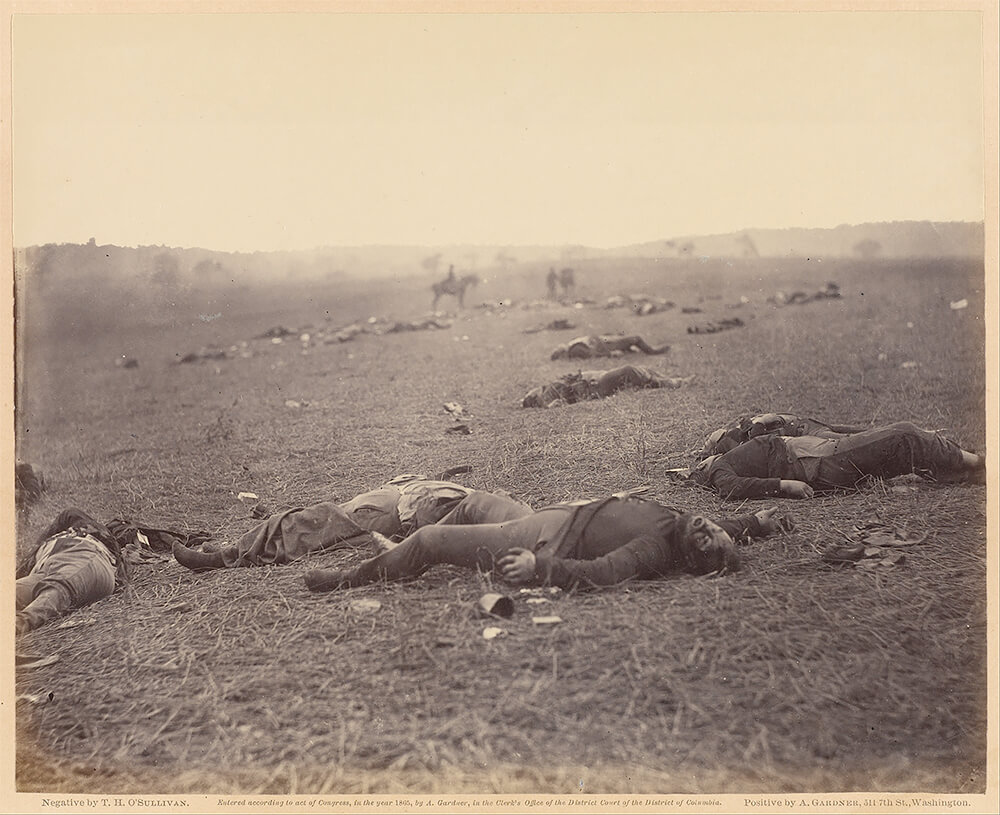

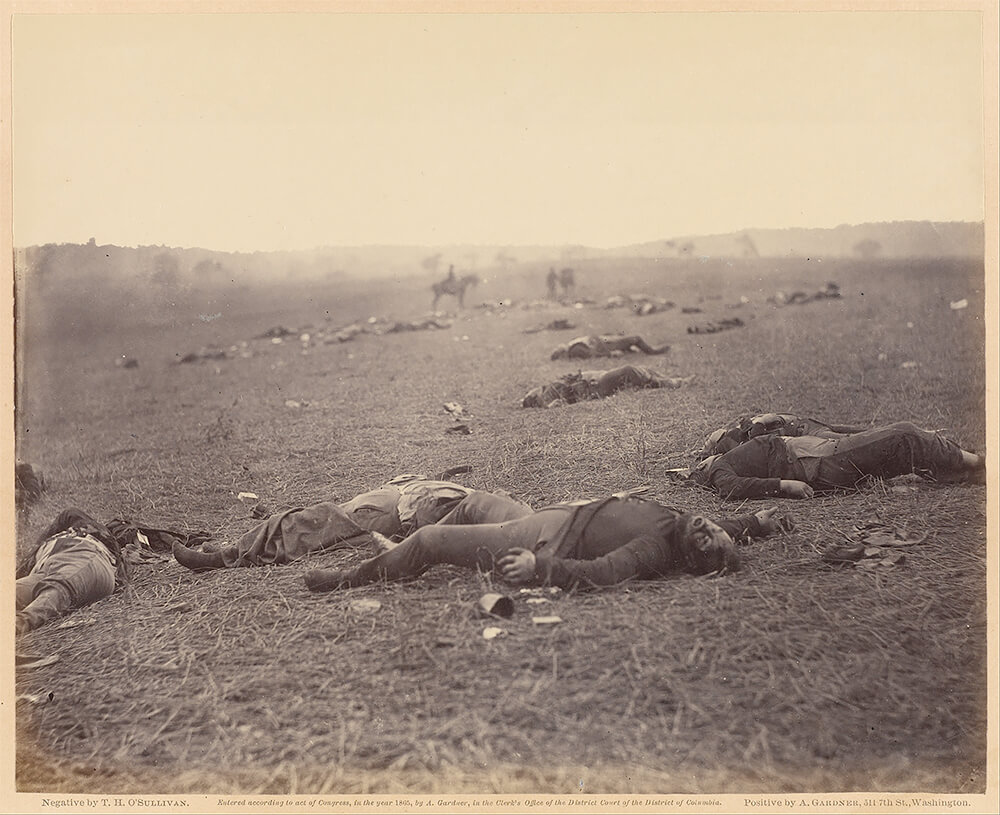

The origins of documentary photography can be found in the 19th century, with the invention of the daguerreotype by Louis Daguerre and the calotype by William Henry Fox Talbot. These early photographic processes allowed for the creation of images that were far more detailed and permanent than any previously known medium. Photographers like Timothy O'Sullivan and Mathew Brady turned their lenses toward documenting the American Civil War in the 1860s, producing some of the earliest examples of war photography. These images conveyed the harsh realities of war, reaching the public in a way that words alone could not.

The Harvest of Death: Union dead on the battlefield at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, photographed July 5–6, 1863 © Timothy H. O'Sullivan

Union soldier by gun at US Arsenal, Washington DC, 1862 © Mathew Brady

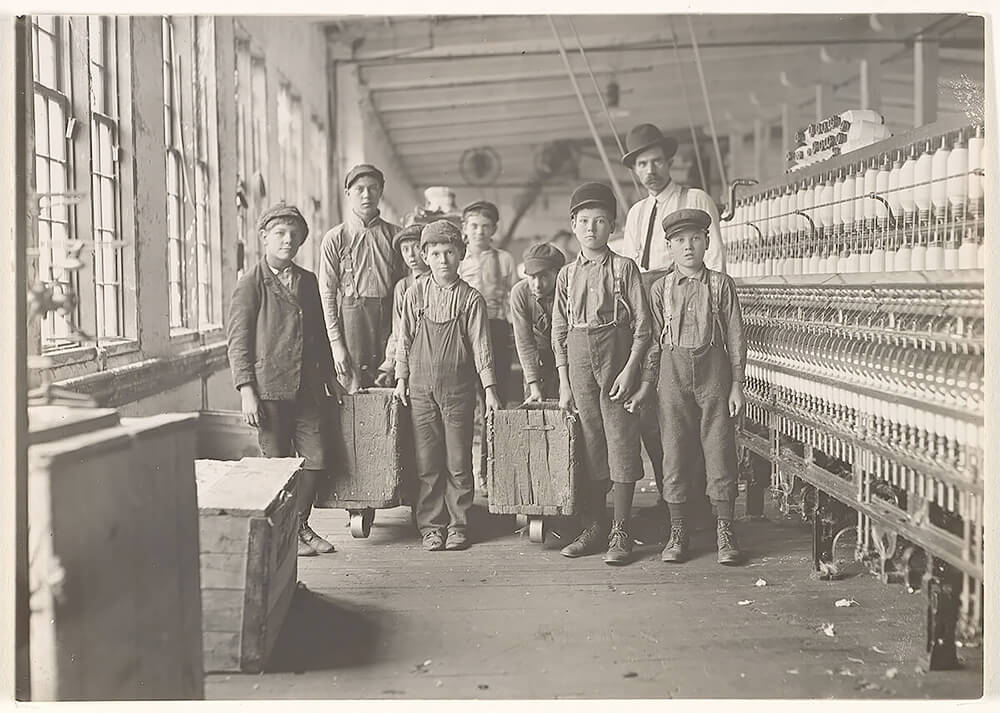

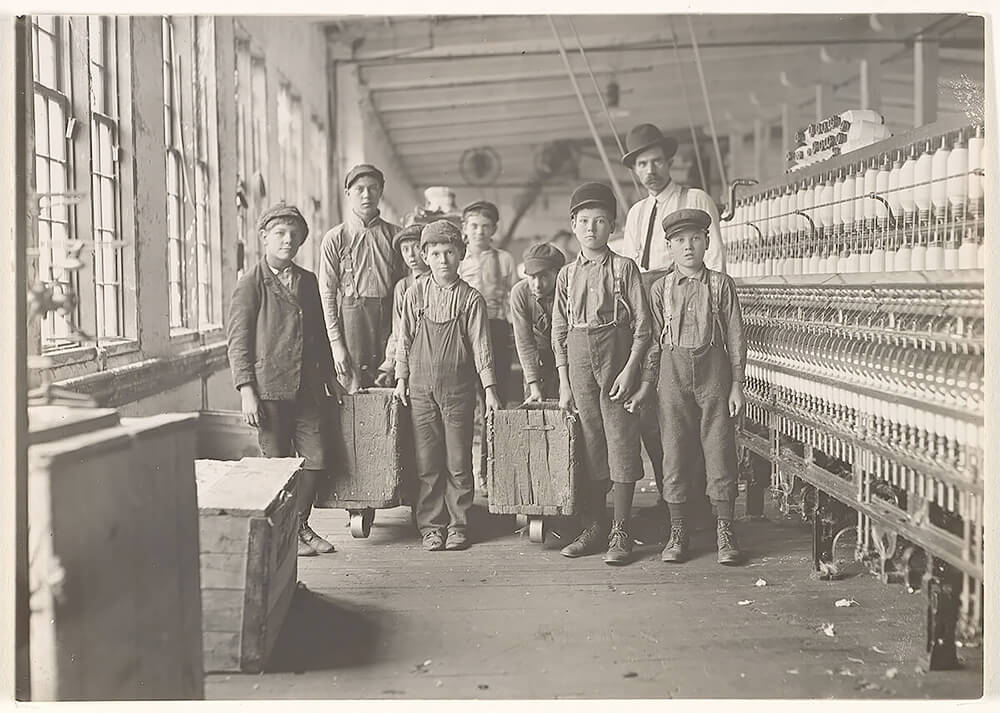

One of the most iconic names in the history of documentary photography is

Lewis Hine. Working in the early 20th century, Hine utilized photography as a tool for social reform. His photographs exposed the exploitative conditions faced by child laborers in the United States. By capturing images of children in factories, mills, and mines, Hine's work played a significant role in advocating for child labor laws and reforming labor practices.

Uill Children -440, South Carolina MET 1908 © Lewis Hine / CCO

With the outbreak of the First World War artists increasingly focussed on photography’s ability to record the horrors happening around the world.

‘The inherent violence of the war soon engendered a new commitment by the world’s photographers to document every aspect of the fighting, from life in the trenches to views of fighter planes cruising the skies. Nothing was left hidden from the camera’s burrowing eye.’' -- The Metropolitain Museum in New York

The quantity of photographs captured during wartime is staggering, yet a significant portion of the photographers involved in this endeavor remain nameless and unrecognized. Among the few who managed to step out from the shadows, individuals like the British photographer Ernest Brooks (1876-1957) and the Canadian counterpart, William Rider Rider (1889-1979), stand out. While their work was undoubtedly of high quality, it carried an air of uniformity and predictability. Notably, Brooks holds the distinction of being the sole official photographer entrusted with documenting the Battle of the Somme in 1916, earning him the status of the longest-serving British war photographer.

Wounded British soldiers and German prisoners heading to the rear during the Battle of Bazentin Ridge (part of the battle of the Somme), 19 July 1916 © Ernest Brooks /Imperial War Museums

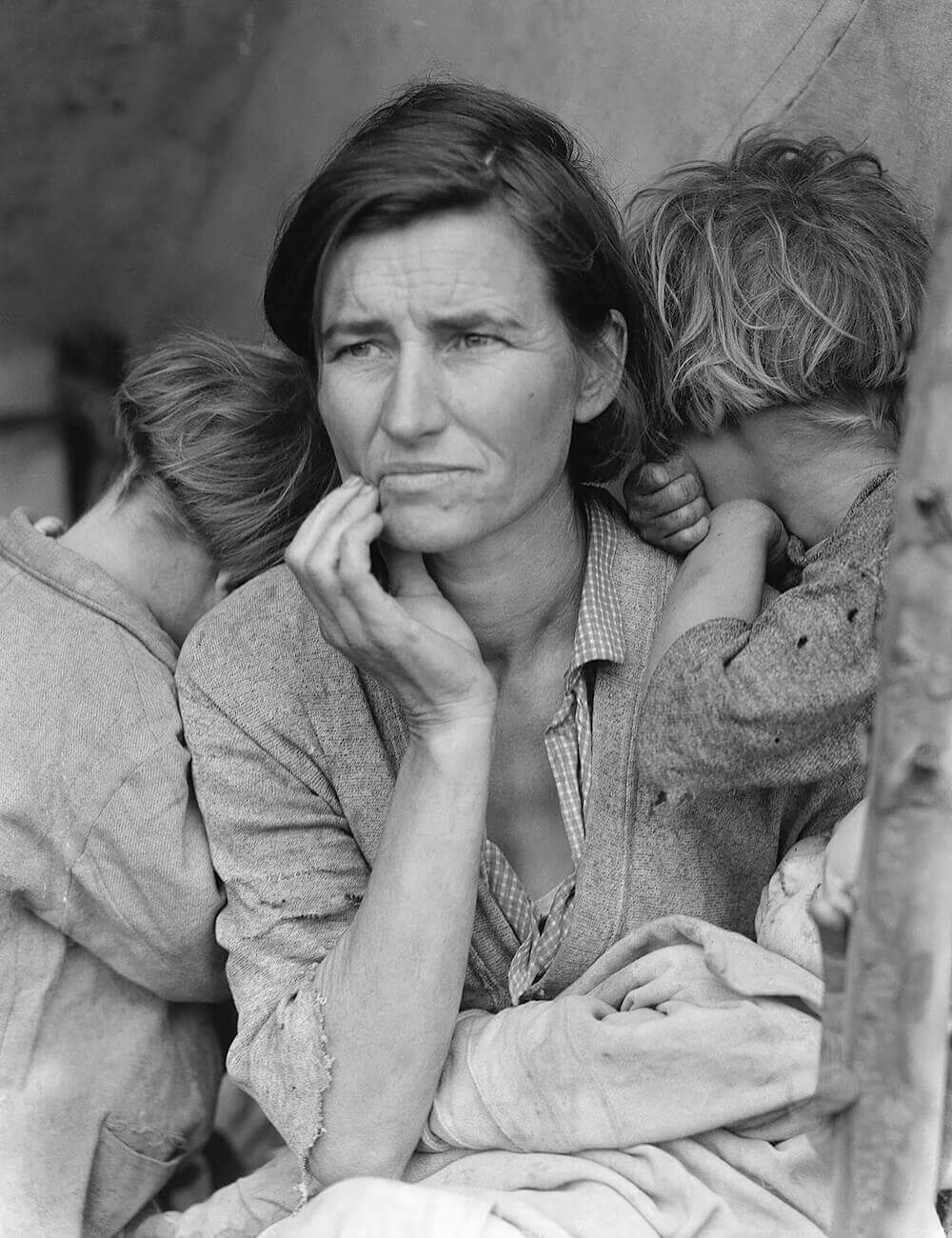

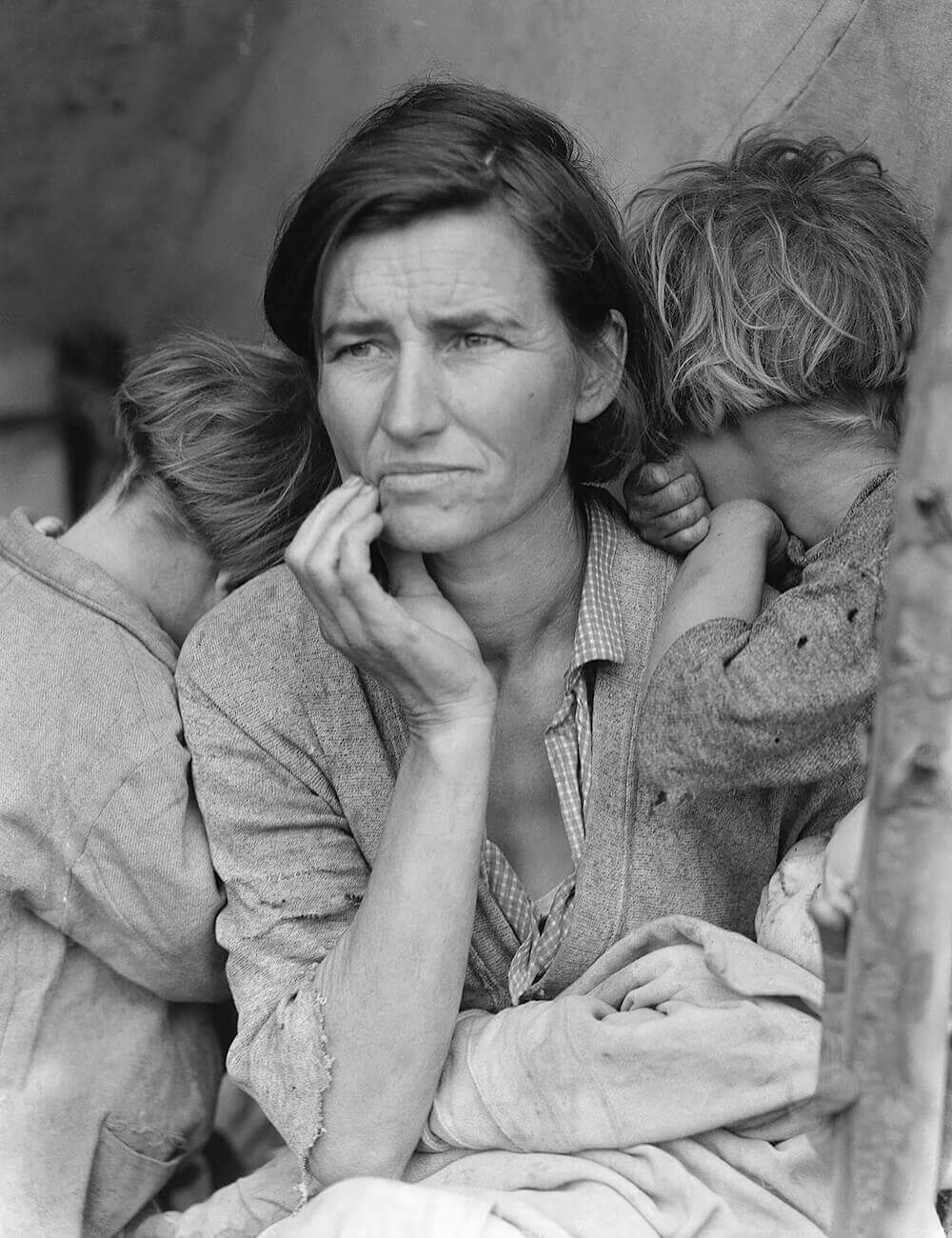

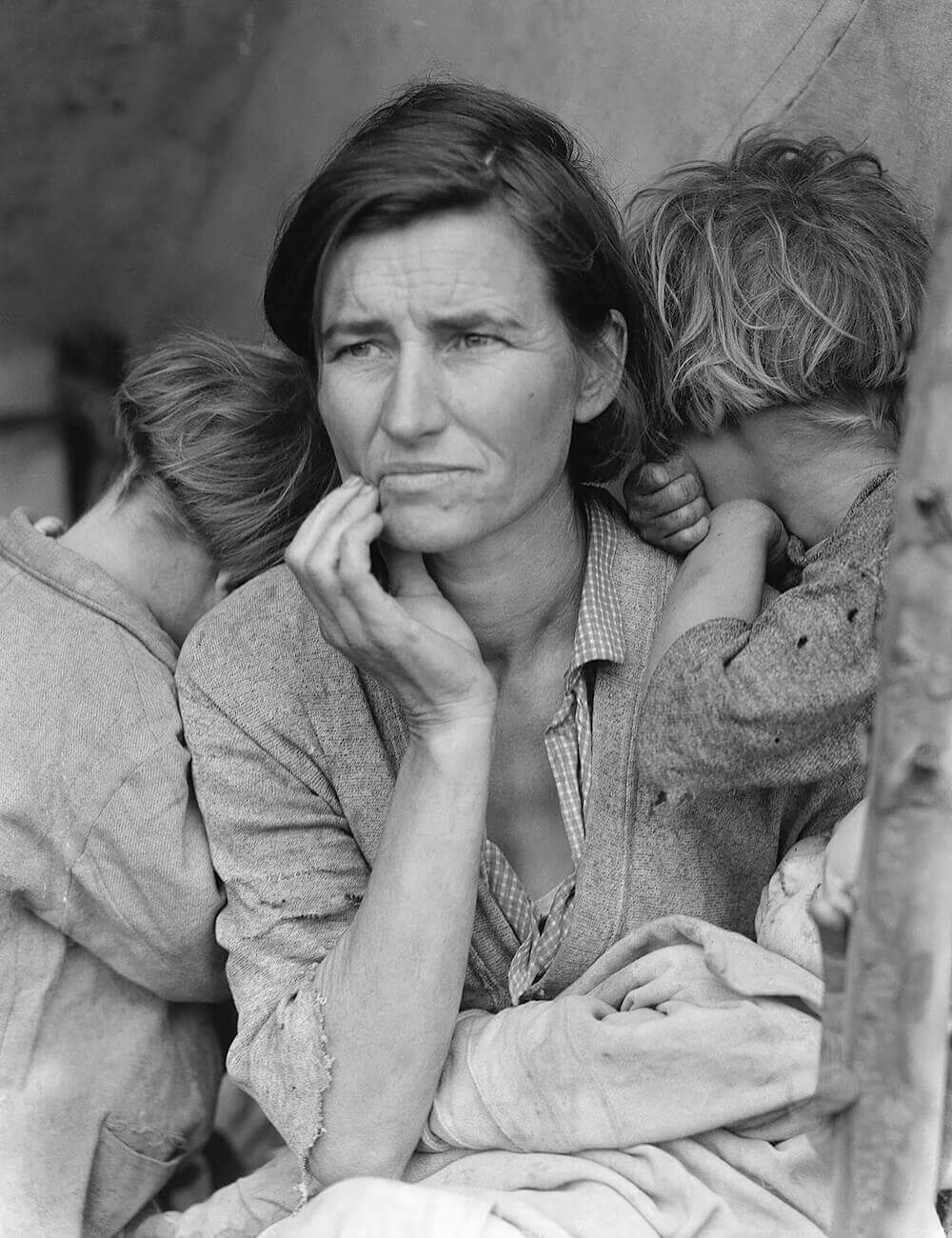

The period between the two wold wars was marked by social and political consciousness. The Farm Security Administration (FSA) played a significant role in the development and promotion of documentary photography. As part of the New Deal program, it aimed to address rural poverty and agricultural issues during the Great Depression. One of the ways it did this was by employing photographers like

Dorothea Lange, and

Walker Evans to document the living conditions, struggles, and resilience of rural Americans.

Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother is an enduring symbol of the hardships faced by Americans during that period. Lange's work, alongside that of other photographers employed by the Farm Security Administration, effectively conveyed the economic and social challenges of the time.

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, 1936, Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress © Dorothea Lange

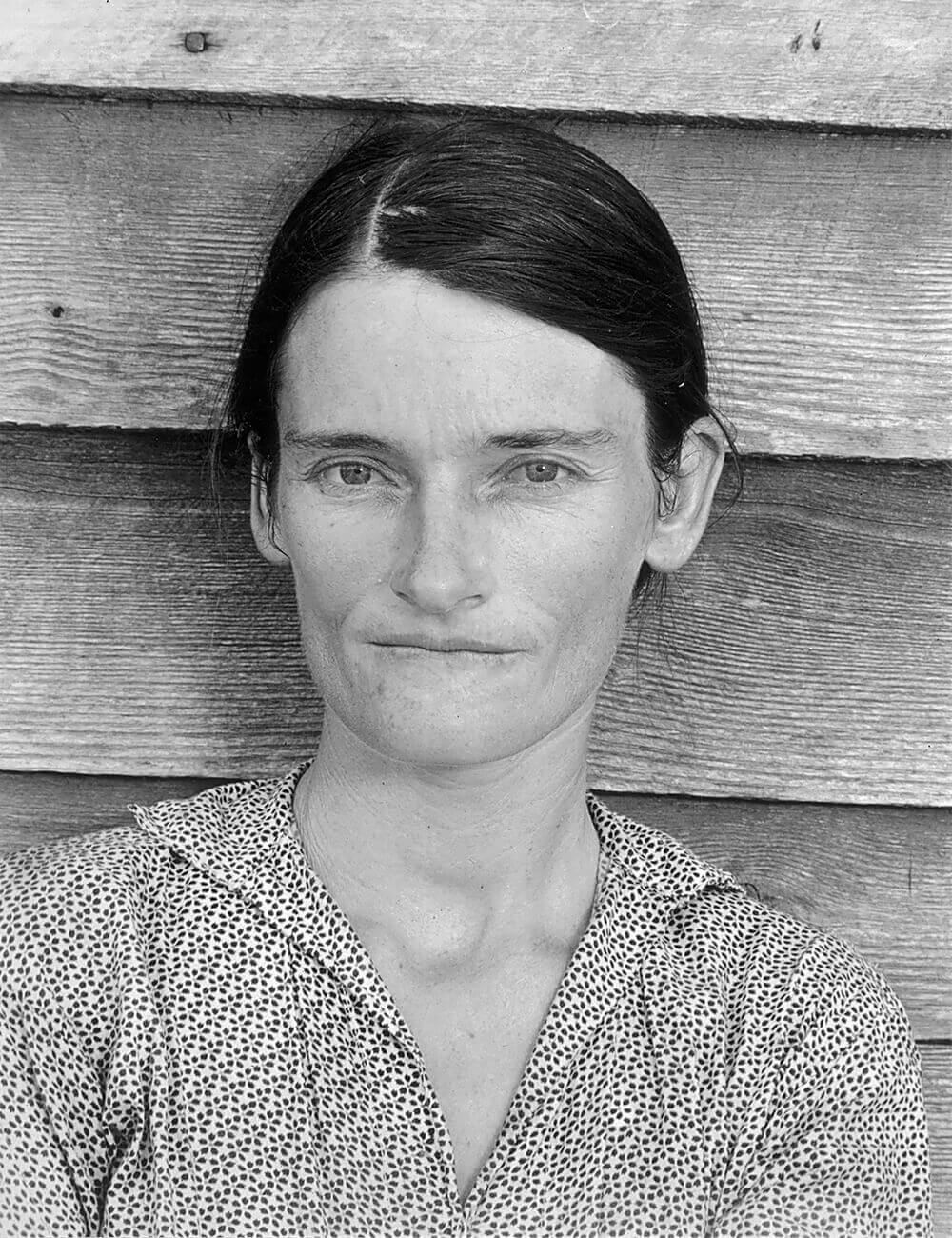

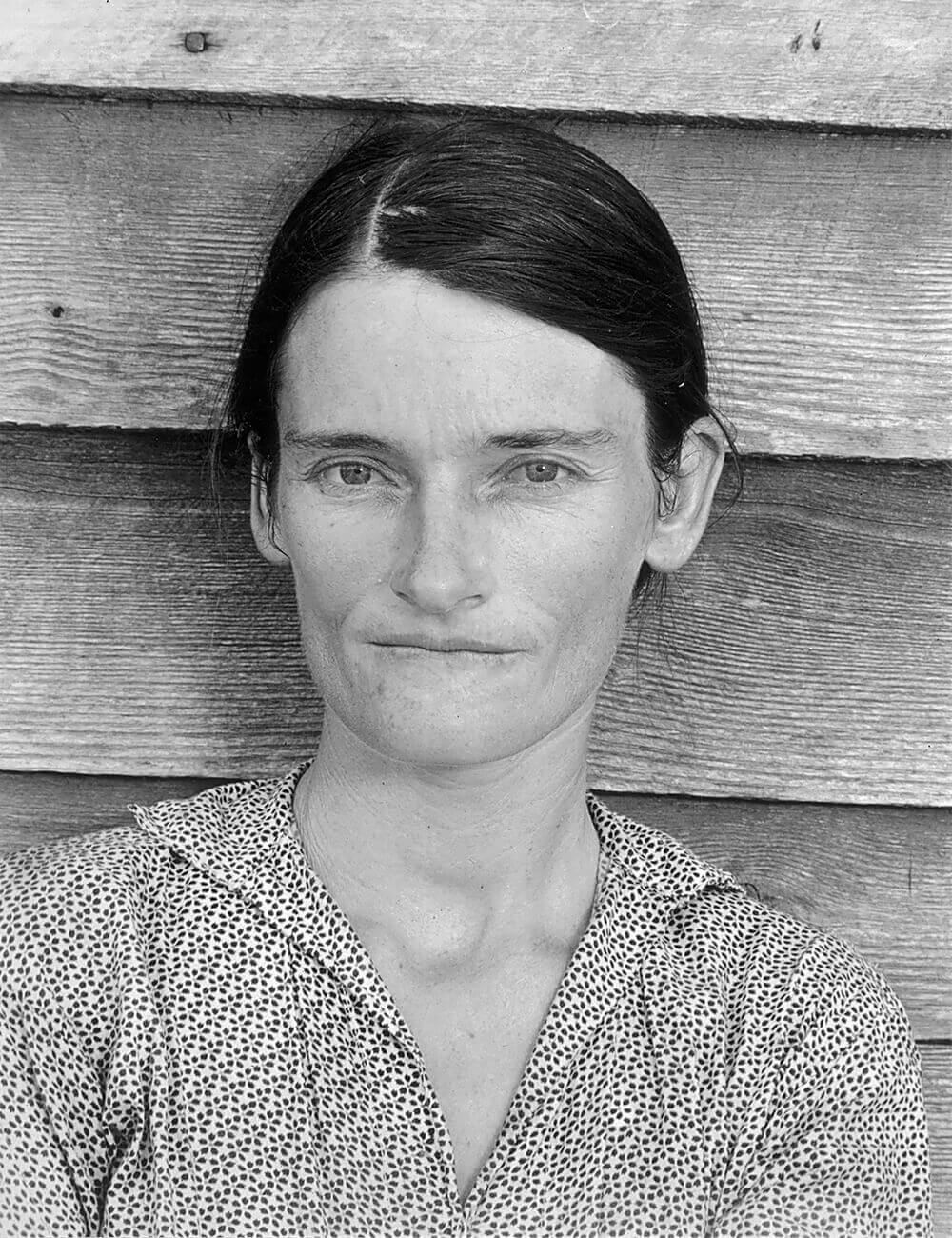

was also an American photographer best known for documenting the effects of the Great Depression for the Farm Security Administration (FSA).

llie Mae Burroughs, 1936, Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress © Walker Evans

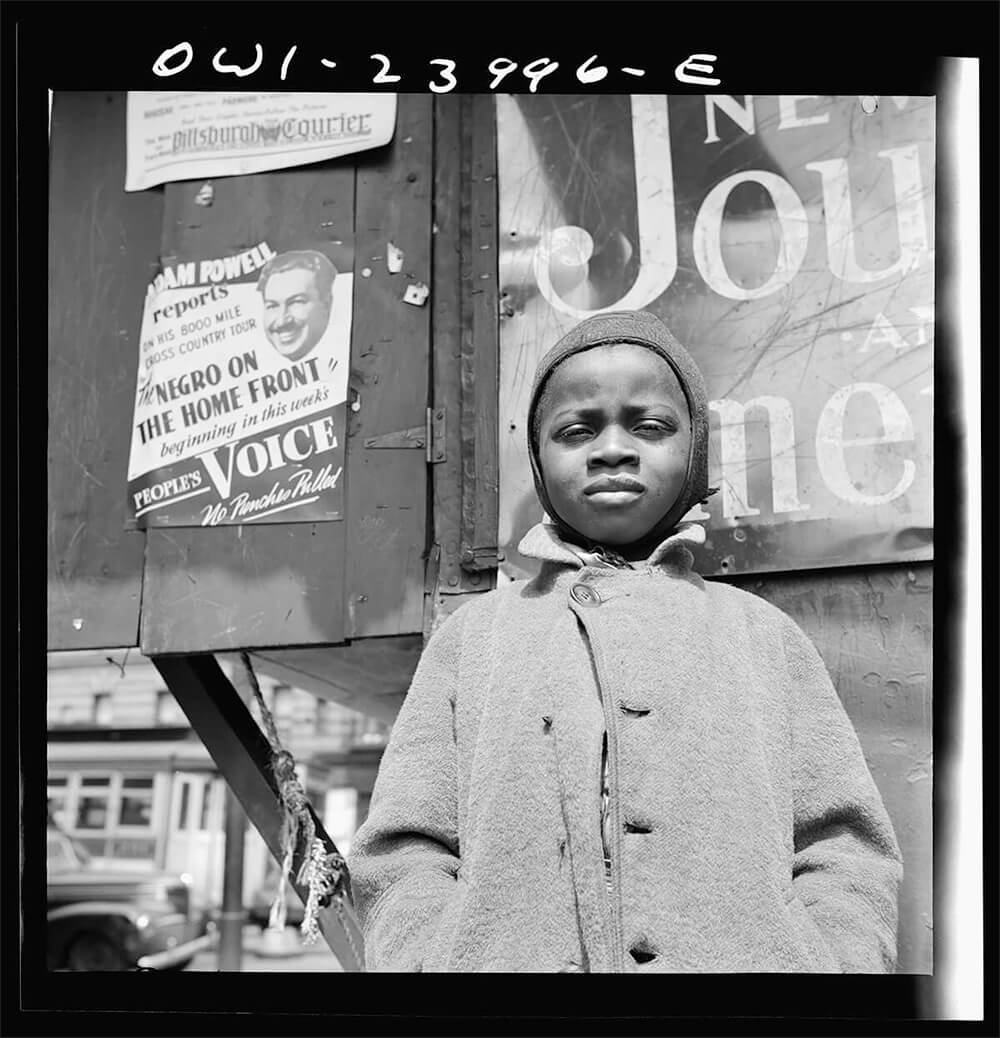

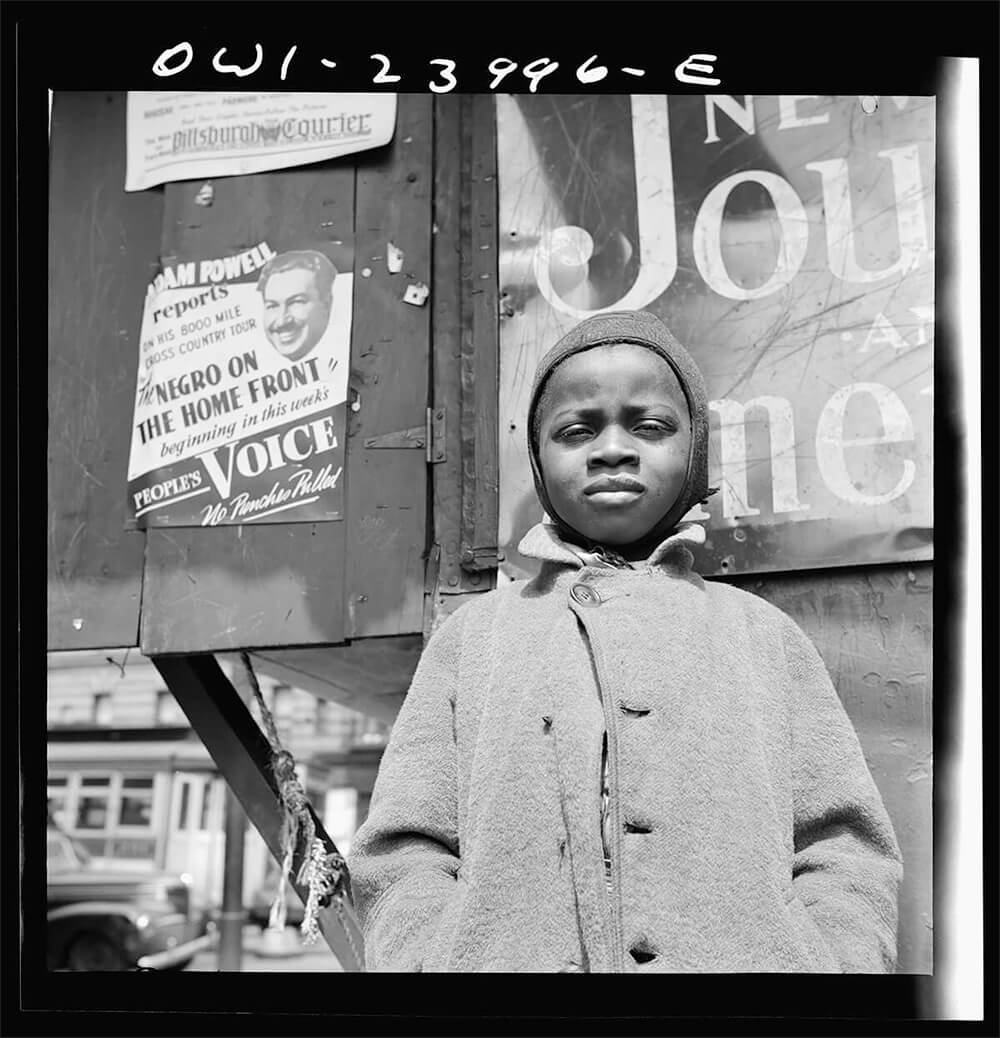

, made photographs highlighting racial, economic, and social disparities. He began to chronicle the city's South Side black ghetto and, in 1941, an exhibition of those photographs won Parks a photography fellowship with the Farm Security Administration (FSA). After the FSA disbanded, Parks remained in Washington, D.C. as a correspondent with the Office of War Information.

New York, New York. A Harlem newsboy May 1943 © Gordon Parks

World War II witnessed an unprecedented utilization of professional, military, and freelance photographers, marking the birth of the contemporary war photographer as we understand the role today. Renowned names like

Robert Capa (who also also covered the Spanish Civil War with his partner Gerda Taro and colleague

David Seymour (CHIM), George Silk,

Margaret Bourke-White, and

William Eugene Smith emerged during this period, gracing the pages of magazines and newspapers and setting a standard for those who would follow in their footsteps.

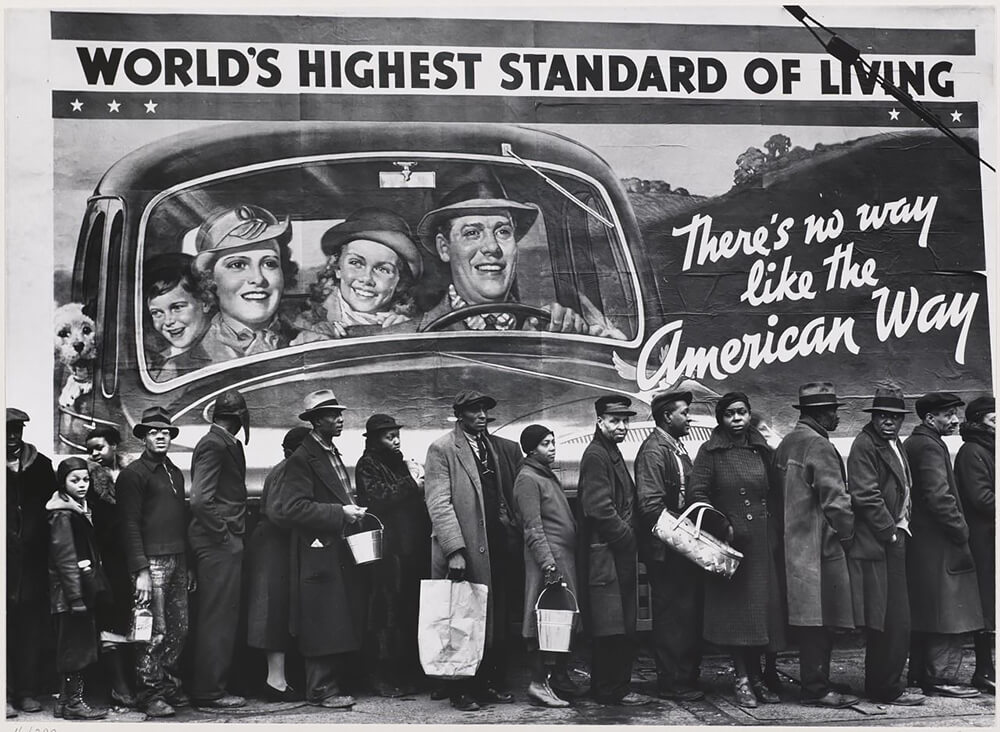

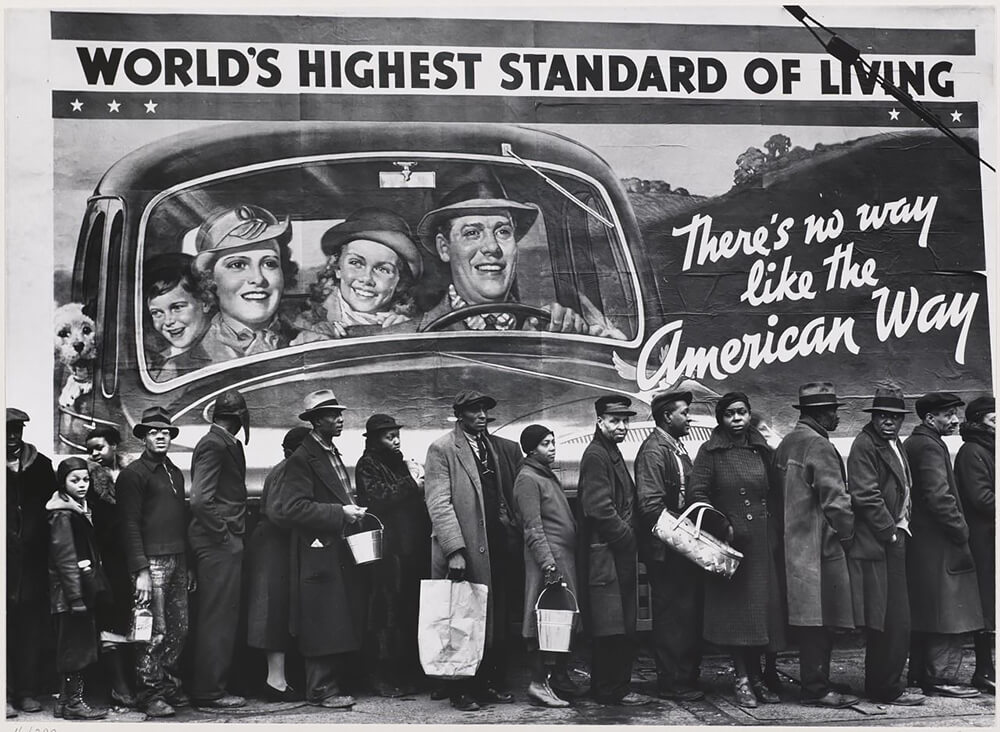

‘“Difficult as these things may be to report or to photograph, it is something we war correspondents must do. We are in a privileged and sometimes unhappy position. We see a great deal of the world. Our obligation is to pass it on to others.” -- Margaret Bourke-White

World’s Highest Standard of Living also known as At the Time of the Louisville Flood in Louisville, Kentucky after the Ohio River flood of 1937. It first appeared in Life Magazine’s February 1937 issue. © Margaret Bourke-White

Technological advancements also played a pivotal role, having evolved significantly since the 1920s. Photographers now had access to more compact and agile cameras like the Rolleiflex, Contax rangefinder, and Leica. These advancements freed photographers from the constraints of cumbersome equipment and extended exposure times, enabling them to document active combat with unprecedented flexibility. For instance, Robert Capa's iconic, blurry images from D-Day were captured using a Contax II, plunging the world into the chilling waters of Normandy and the chaos of wartime.

However, not all of World War II's iconic photographs depicted ongoing conflicts. Two of the most famous images from the era immortalized moments of victory and the cessation of hostilities: Joe Rosenthal's Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima and Yevgeny Khaldei's Raising a Flag Over the Reichstag.

Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, 23 February 1945 © Joe Rosenthal

In the post-World War II era, the world of photography underwent a remarkable resurgence, fueled by fresh concepts, innovative techniques, and an ever-expanding array of opportunities for sharing and exhibiting images. With the war's end, numerous photographers were eager to showcase their work in the flourishing realm of illustrated magazines, which enjoyed a period of significant growth during this dynamic period.

In 1947,

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa,

George Rodger and David ‘Chim’ Seymour founded the

Magnum photographic agency, originally set up to document the realities of post-war life, with important members including

Eve Arnold and Stuart Franklin.

Starting in the 1940s, documentary photography underwent a profound transformation. Traditional documentary styles, which often tackled sensitive subjects, had long been associated with the hardships of the Depression era. Even the very term documentary had started to carry negative connotations. The public yearned for a more poetic and less ideologically driven approach to photography, one that could vividly depict the nuances of everyday life in the postwar era, surpassing the activism of the past.

Documentary photography began to shift its focus away from narrowly defined social issues, opting instead to document the routines of daily life. Each photographer, however, developed a personal inclination for certain aspects over others. This renaissance found a fertile ground in France and eventually gave rise to what we now recognize as humanist photography.

Robert Doisneau,

Wily Ronis,

Sabine Weiss,

Edouard Boubat, Henri Cartier-Bresson are some of the movement most eminent representatives.

Une rue à Naples, 1955 © Sabine Weiss

The emergence of a more personal, evocative, and intricate style of documentary photography is often attributed to Swiss-American photographer

Robert Frank. His book The Americans is widely acknowledged as a pioneering example of this genre.

Frank's photographs explored the complexities of American society and culture, revealing both its beauty and its flaws. His candid and unfiltered approach to photography ushered in a new era of documentary work.

''The truth is somewhere between the documentary and the fictional, and that is what I try to show. What is real one moment has become imaginary the next. You believe what you see now, and the next second you don’t anymore.'' -- Robert Frank

During the late 1950s and 1960s, several photographers expanded upon the concepts of beauty and brutality by delving deeper into the intricate social dynamics of urban settings. In contrast to the photographers of the 1930s, individuals like

Garry Winogrand,

Lee Friedlander, and

Diane Arbus were not focused on reforming American society. Instead, their aim was to meticulously capture the multifaceted, bizarre, and tumultuous aspects of it.

By the late 1960s and 1970s, other photographers, such as

Robert Adams and Lewis Baltz, looked beyond conventional notions of natural beauty to explore the despoliation of the urban and suburban landscape.

Color photography also came into play.

As the lines between photographic genres blurred, visionaries such as

Larry Fink and

Danny Lyon played a pivotal role in reshaping the landscape of documentary photography. Their photographs transcended conventional storytelling, evolving into a fusion of art, historical artifact, evidential record, and personal testimony.

Pat Sabatine’s 8th Birthday Party, Martins Creek 1977 © Larry Fink

But the 60s and 70s also saw brutal conflicts and images kept showing the horrors of war,

Don McCullin and Nick Ut are some of the photographers who kept covering areas of armed conflict.

The Terror of War © Nick Ut, Associated Press

's photographic portfolio stands out for its unfiltered and emotionally charged portrayal of her subjects and their lived experiences, solidifying her status as a prominent figure within the domain of documentary photography starting in the 70s. Her photography has earned widespread recognition for its candid and intimately revealing nature, delving into subjects like human relationships, sexuality, substance dependency, and the LGBTQ+ community. One of her most iconic photographic series is The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, an intensely personal and documentary-inspired project that vividly captures the lives of not only the artist herself but also her circle of friends in the urban backdrop of New York City during the late 1970s and 1980s.

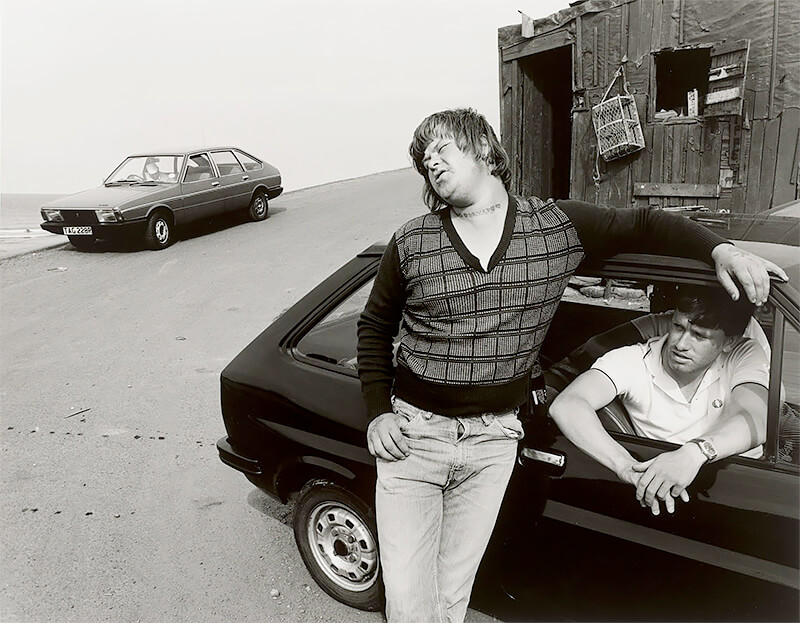

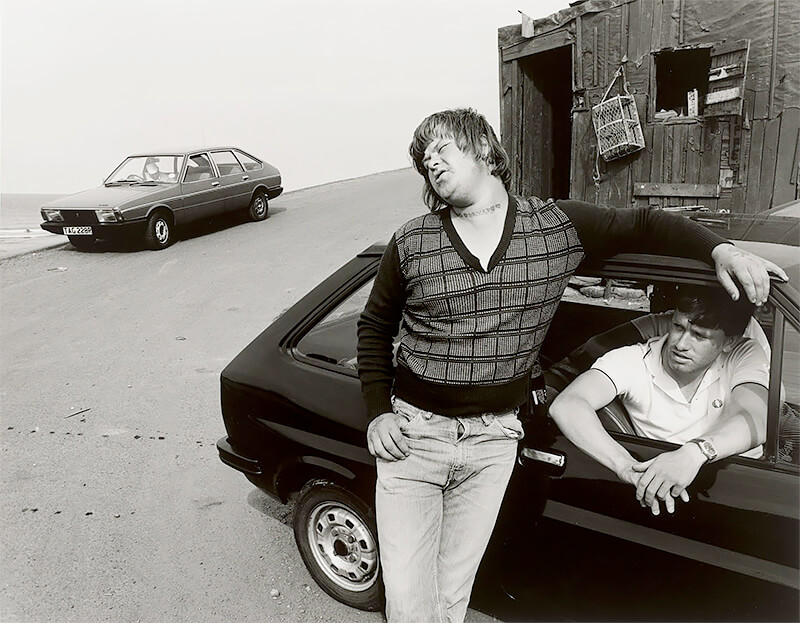

Chris Killip's book, In Flagrante, a collection of photographs made in the North East of England during the 1970s and early 1980s, is now recognized as a landmark work of documentary photography. Other bodies of work include the series Isle of Man, Seacoal, Skinningrove and Pirelli.

Bever’s First Day Out, Skinningrove, North Yorkshire 1982 © Chris Killip

To be continued...