Seth Dickerman is a master manipulator of the wide spectrum of light densities that reflect off the surface of a photographic print and enter into our field of vision. His singular intent in making prints is to bring out the best an image has to offer, which means giving an image the ability to hold our attention, to engage us, and to allow us to discover something about an image that is meaningful and significant.

Working from his shop in San Francisco’s SOMA district, Seth has printed the work of legendary figures like

Dorothea Lange and renowned rock ‘roll photographers

Ethan Russell, Jim Marshall, Bob Seideman, and others. He is also an accomplished photographer—is there a master printmaker who isn’t? Recently, he exhibited an attention-grabbing body of work titled “Currency,” which is a study of U.S. presidential portraits found on coins and bills. Seth refers to these images as “history books in disguise.”

Seth is also a patient teacher and mentor to any level of photographer who comes into his studio to have prints made. His website makes a welcoming offer to all who are passionate about photography and image making: “Our friendly staff loves to share their expertise and experience. Come in, load up your photos on a Mac workstation, sip on an organic espresso or tea, and let us help you create the perfect print.” In Godfather terms, this is an offer no photographer should refuse.

I have spent countless hours at Dickerman Prints wired on the organic espresso while preparing for a portfolio review or an exhibition. I have gained tremendous insights from Seth about how to approach the editing and printing of my own work. Because I am extremely grateful for our working relationship, I am especially pleased to present the following interview with with Seth.

Jon Wollenhaupt: When did you start Dickerman Prints?

Seth Dickerman: I moved from Pittsburg to the Bay Area in 1995 and soon thereafter opened Dickerman Prints. My work was entirely analog. In 2007, Robyn Color, then San Francisco’s best photo lab, went of business. I purchased their digital printing equipment, which included a Polielettronica Laserlab, an amazing Italian printing machine. This printer makes Type ‘C’ photographic prints of astonishing quality from digital files. Purchasing that printer ended my nearly 40 years of conventional darkroom work. In August of 2012, we relocated to our current home in San Francisco’s SOMA district.

There are so many facets to creating a compelling, persuasive photograph. Most people are unaware of the complexities involved in making a high-quality print, which is an entirely separate and demanding skill set.

Yes. There’s so much more to it. You can make an infinitely variable range of prints from a single image. When I’m in nature out shooting, I’m very much in the moment, not thinking so much about what can I make out of it. My process is different in ways from Ansel Adams’ approach. He described previsualizing his print while exposing the film. I’m not that premeditated. In fact, my shooting is often ahead of my awareness of any specific concept or idea. I often respond to a scene I want to photograph, and then later, down the road, I realize that I was reacting subconsciously to something that illustrates my philosophy or an idea. Eventually, that point of view becomes more conscious.

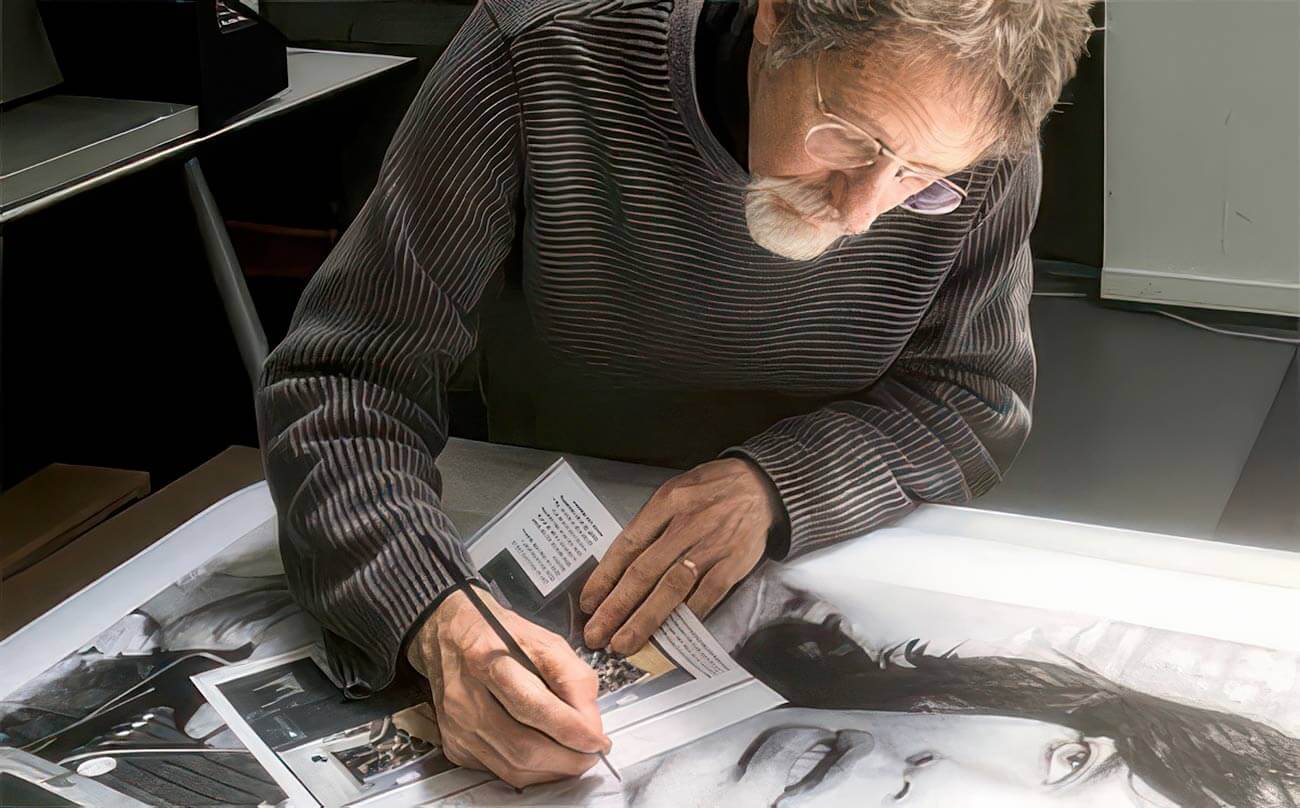

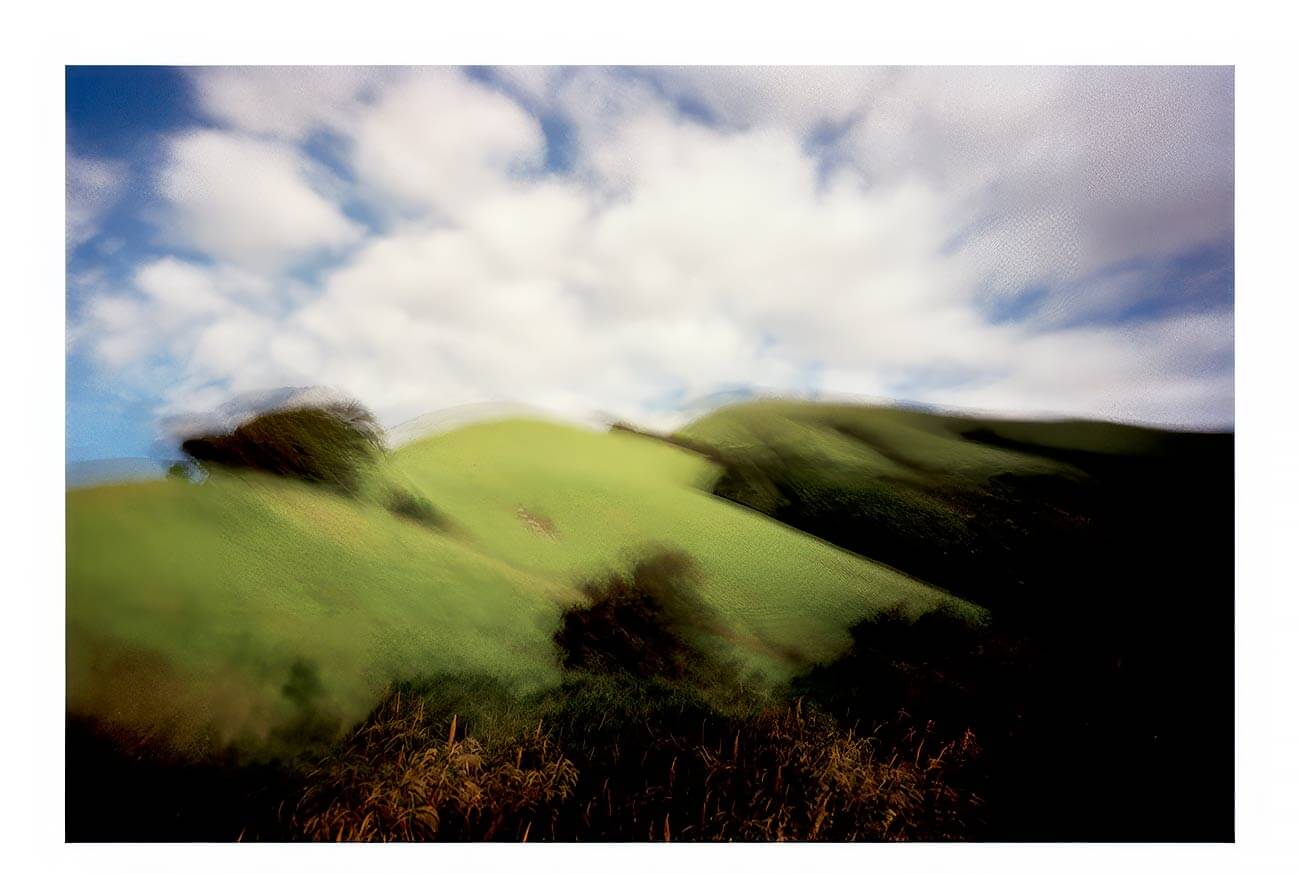

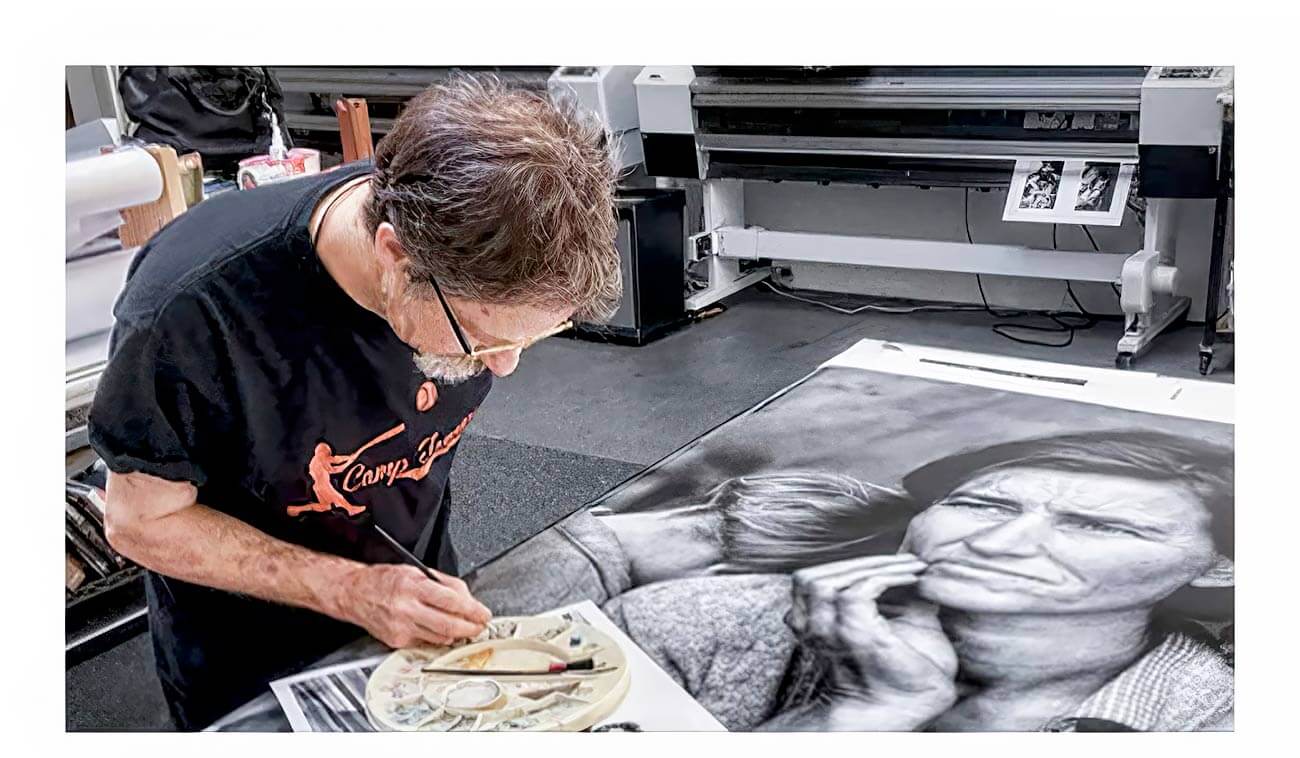

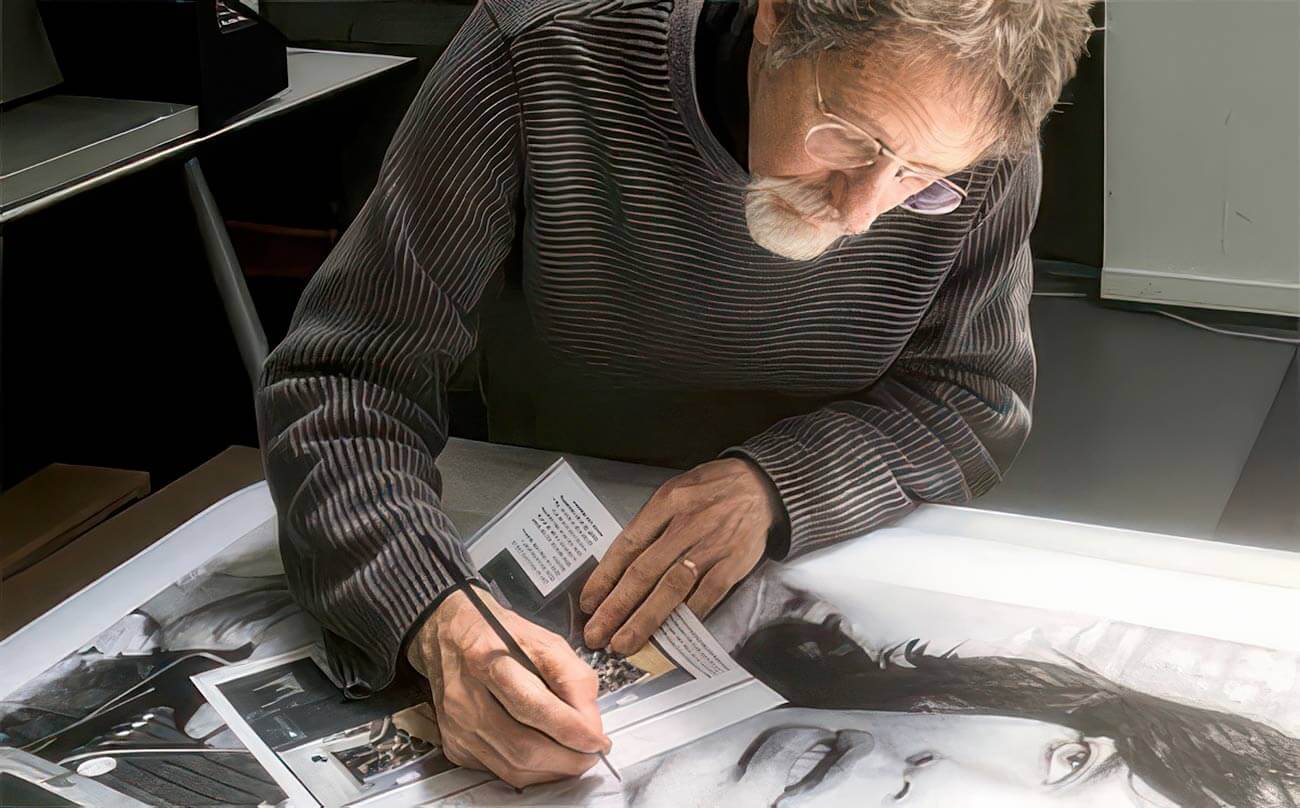

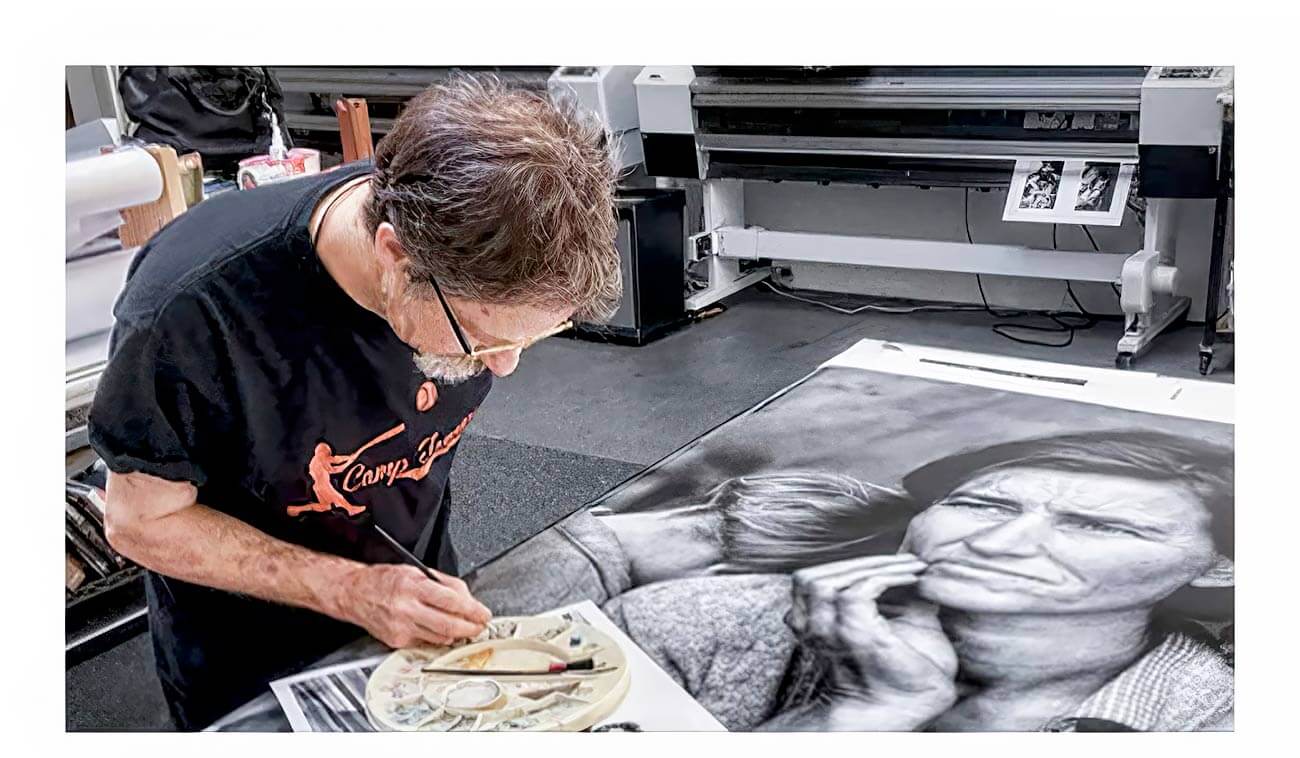

Seth Dickerman at work in his SOMA Studio

I had a long-time client, a wonderful photographer named Beth Yarnelle Edwards, who had a show at the museum. Through the photographs we printed for that show, the museum’s curator of photography, Drew Johnson, came to know me and my work. Some years later, they were doing a show to commemorate the 50thanniversary of the Museum’s acquiring Dorothea Lange’s personal archive, which had been entrusted to them by her husband, Paul Taylor. I was asked to make a number of new prints of some of Lange’s best known images, which incredibly exciting. Because she’s been my hero since I was a lad. We might not even be having this conversation if I hadn’t been so excited by Dorothea Lange’s work when I was 12.

Making those prints was a real thrill – several of them were very large: 5 x 7 feet. Being able to print those pictures 50 years after my first encounter with her work was great. Some of the big ones were of things I grew up loving, like “Tractored Out,” “The Road West,” and “Crossroads Store.”

What process did you use to create those prints?

They’re archival pigment prints, which are also known as inkjet or giclee prints. I worked with digital files that were made, in most cases, directly from the original negatives. I increased the resolution of the files and painstakingly cleaned them up. I worked nights and weekends to get them perfect. It was a labor of love.

What other work have you done for the Oakland Museum?

In 2019 I printed the work of one of the greatest photographers most people have never heard of —

Andrew J. Russell. He was a Civil War photographer but is better known for his documentation of the building of the Transcontinental Railroad. The museum had a show commemorating the 150th anniversary of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad. They have the entire archive of the work Russell did for the Union Pacific Railroad, which is amazing. He shot wet plate collodion, a 19th century process that exposes the image on a big glass plate that is coated with a photographic emulsion and is about 11×14 inches. With that process, the image has to be exposed while it’s still wet, and then processed immediately.

Russell shot incredible landscapes with great steam locomotives, and train tracks, rivers, mountains, bridges, and, sometimes, hundreds of people. The detail of the images created by the wet plates is absolutely astonishing. Originally, these images could only be made as contact prints, the same size as the plates, a process that does not allow for much burning and dodging.

To make prints for the exhibition, the Oakland Museum scanned Russell’s original plates on a flatbed scanner, like making digital contact prints, and they sent me the digital files. It was amazing to open up those files and zoom in and see all the people – sometimes hundreds of them – in great detail, wearing vests, hats, sporting grand mustaches, there are soldiers with swords.

Transcontinental Railwoad © Seth Dickerman

I’m always on the side of the photographer. I try to get into their head and do what I think they would want me to do, which is to make a print that will hold the viewer’s attention, to make a print that will draw the viewer in, and to show the viewer all of the detail possible so they can learn as much as possible from the work.

Dorothea Lange had no inhibitions about manipulating her images in order to make them serve her purpose. She would crop and burn things way down. She did very interesting things to her prints to get the results that she wanted. Recently I made another set of prints of her work for the Oakland Museum’s permanent collection. While making those prints, I tried to respect her intent as I understand it.

What techniques do you use to create a printed image that engages the viewer and holds their attention?

The techniques mainly involve what is referred to in the darkroom as dodging and burning, which is a way to locally manipulate the density and contrast, the lightness and darkness, in various places in the image. The difference in those densities is what draws your attention from one place to another. I’m very attuned to how the eye travels around an image, around a flat surface. I’ve been working my entire career to enhance and direct that flow of eye movement, which affects how you perceive an image. I want your eyes and your attention to stay on an image. I want to draw you into that image. Adjusting or manipulating those densities can make the surface of an image appear concave, rather than convex, which will also make it more likely you will be drawn into it. In general, you could say the eye is drawn to light and away from dark. Therefore, we can use those tendencies to guide the eye around very gently by darkening certain areas and lightening other areas. For example, you typically want to darken the edges of a photo, so the viewer won’t go to the edge of a print and off the image. You want them to keep coming back in, circling around, like the way water circles around a drain. You want the viewer to be enveloped by the image yet drawn to the middle.

If I’m printing a landscape, for example, I’m thinking about making it look as three-dimensional as possible. I want it to work like the

proscenium arch around the stage in a theater, that draws the audience’s view deep into the stage. Often, when preparing an image for printing, I feel like I’m turning it inside out because what’s in the middle — the subject — might be darker than what’s on the edges, which makes it difficult to keep the viewer’s attention. To get the most out of that type of image, I’ll open up, or lighten, the middle and darken the edges.

The things I strive for in an image are perspective, depth and volume. I replicate the darkroom techniques of dodging and burning using layers in Photoshop. The beauty of digital techniques is that you have much more control. I essentially print every square inch of an image. I don’t like to leave any information out.

Sounds like you’re orchestrating all these parts of the photo to create a whole.

Yes. That’s what Ansel Adams said: “The negative is the score, and the print is the performance.” I do a lot of orchestrating because I want all the parts to function together, to add up to more than the sum of their parts. But ultimately the hand of the editor should never be detected. It cannot look like you’ve manipulated the image. I might have burned down the corners, but that should not be obvious to the viewer. “Oh, he burned down the corners.”

Let’s talk about the difference between an image on a computer screen versus a printed image. You often speak about the emanating light of the screen versus the light reflected from the print surface.

There’s a huge difference between the two. When you’re looking at an image on a screen, the image itself becomes the light source, which is interesting, and also weird; the image is being blasted out at you via LEDs. It’s hard to look at a screen for a sustained period of time without feeling fatigued. More importantly, the screen simply cannot draw you in the way a print can. Looking at a printed image is a completely different experience.

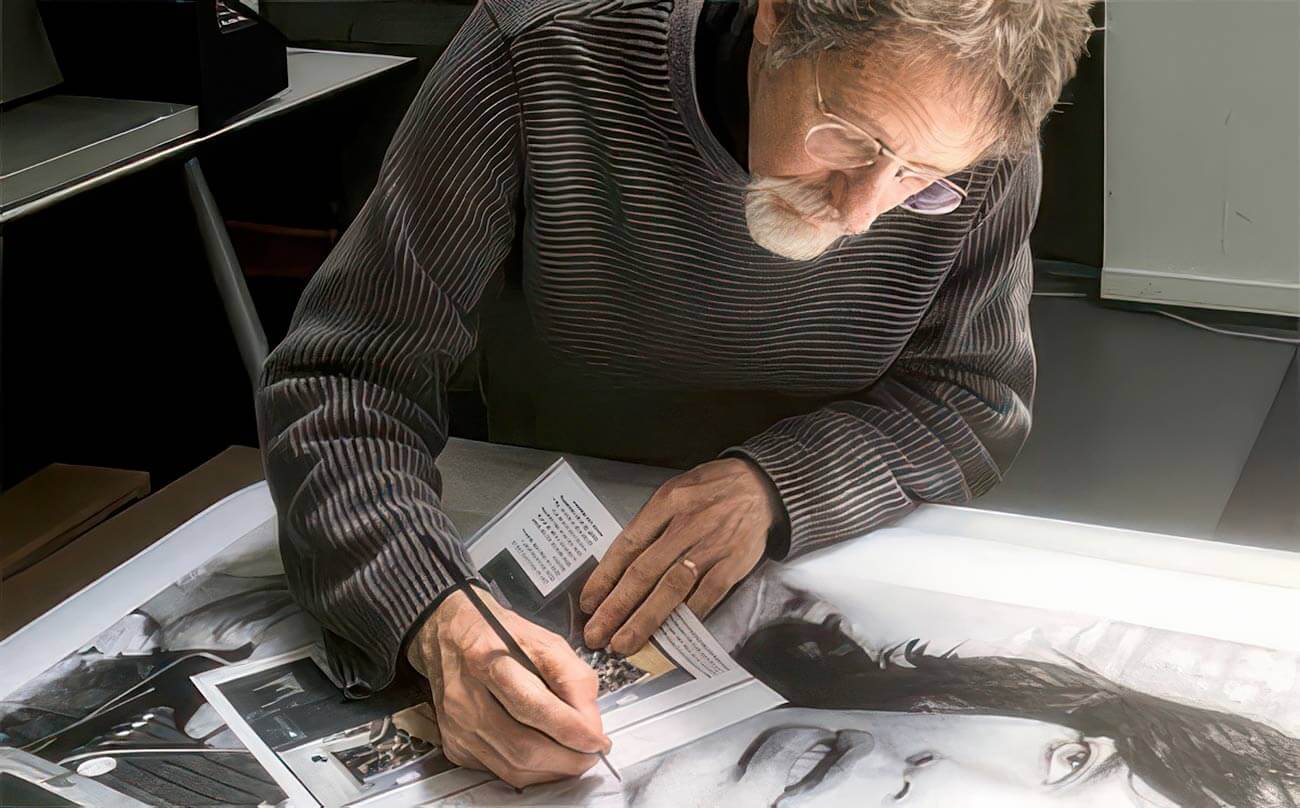

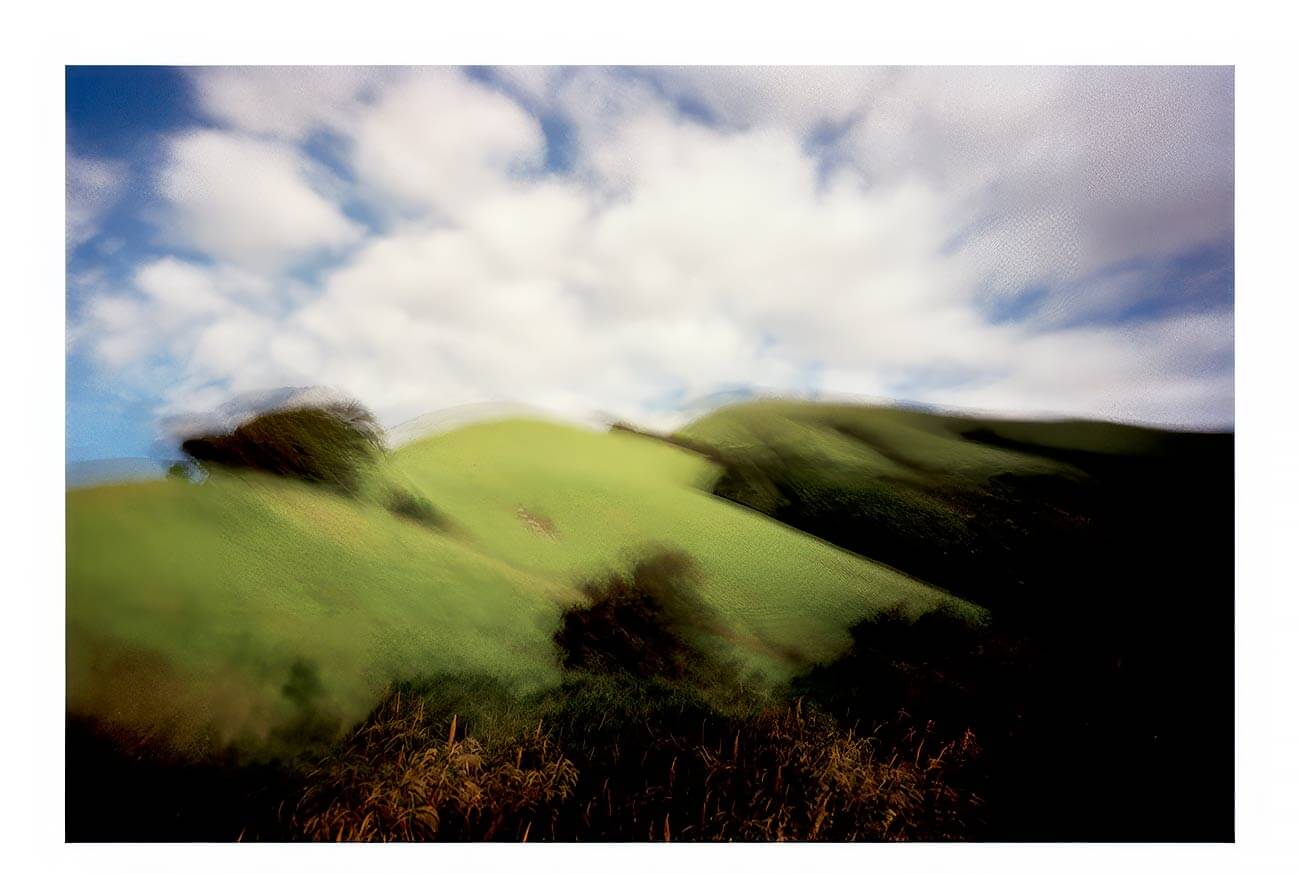

Moonlit Marin Headlands © Seth Dickerman

is a great photographer. He has photographed the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, The Who and pretty much everybody. He had moved up here from LA and was looking for a new lab. He just wandered into our studio one day to check us out. He saw my big Sergeant Pepper logo on the wall, and we hit it off. We’ve been working with him for quite a while now, which is really fun. He shot the Beatles’ last portrait as a group, he was on the rooftop at Abbey Road. How cool is that?

We’ve also been working with the estate of

Jim Marshall for a long time. Jim was the photographer who captured some of rock’s most iconic moments: Jimi Hendrix burning his guitar at Monterey Pop and Johnny Cash flipping the bird at San Quentin. A very colorful , character, he photographed everybody, and he got in really close. We do get a kick out of printing Ethan and Jim’s work for sure.

But we love to print for everybody. We meet very interesting people! We have an amazing variety of customers with whom we love to work. My mission with all our clients is to exceed their expectations. It can a family picture, a wedding picture or pretty much anything. We really like restoring old pictures especially. It’s very satisfying work.

Let’s talk about your work as a photographer. What you like to shoot, do you shoot film or digital, and what print process do you favor?

I became a professional printer because I was a photographer. I wanted to learn as much as I could about printing so I could produce my own work, which I still do. My work is primarily landscapes, I call them metamorphic landscapes. I shoot them with a Leica rangefinder camera, so I can watch the image unfold while the shutter is open. I take very long exposures because I’m interested in showing the fluidity and subjectivity of the experience. The long exposures also give more of an opportunity to ease the distinctions between earth, fire, water and air; day and night; stillness and motion.

I often shoot by moonlight or by twilight. In the case of moonlight, I shoot when you can’t see any color. At night, the rods in your eyes — the color-sensitive sensors — shut down if there isn’t enough light. But the sky is still blue and the grass is still green at night. I like to shoot that way. I also like to shoot during the day, using neutral-density filters. I do this because I’m interested in extending moments. Instead of freezing time I prefer to make it more elastic, to give a sense of time moving in a still photograph. I think of those images as little movies for the wall.

I also do large-format work. A series of photographs of presidents on currency and coins – very large images made from very small originals – were shot on 4×5 black-and-white film. I’m getting ready to go back to shooting portraits on 8×10 film. I’m going back to 19th century technology, which I really enjoy. But then again, I’ll be printing them with 21st century technology.

I see a lot of interesting work these days that merges 19th century techniques and processes with modern digital techniques.

We are indeed seeing the confluence of digital and analog, which is fascinating. It took me a long time to come around to digital photography. I didn’t start until about 2007. Before then, I was strictly analog – as if I had wall of separation in my mind between analog and digital. When I saw that wall I thought that having any walls in one’s mind is not good, and I got rid of it. So then I began working in both worlds, but as I learned to better integrate them (analog and digital) it became one world for me eventually.

Do you have any exhibitions coming up? How can someone see some of your work?

They can go to my

website or come visit the lab. I’m happy to show my work and that’s where I’ve got it. I have a couple of shows in mind, just to hang at the lab, but I have nothing on the calendar right now.

Seth Dickerman at work in his SOMA Studio