Ann Jastrab: Can you tell us about your background and the origins of your interest in photography? (Where did you study? How old were you, etc?)

Chris Churchill: I came to photography about 20 years ago when I was 17. I had been kicked out of high school and so I enrolled in an alternative school on a farm. As a student, you could go full-time, part-time or independently so I chose the independent track and drove cross-country with a friend. When I got back, I needed another course and had taken a bunch of pictures, so I thought I would propose a photography class. The teacher was very cute and close to my age; the chemistry was literally in wine bottles and the rest is history.

After high school I knew traditional college wasn't for me either. I was passionate about photography so I went up to the Maine Photographic Workshops and enrolled in a 2-year program. The immersion of being there was amazing and being able to interact and listen to such great photographers talk about their work was invaluable to me.

AJ: What path did you take to becoming both a successful commercial photographer and fine art photographer? Do the two paths compliment each other?

CC: To quote a well-known photo editor: 'Every photographer has a weird career.' I never intended to be a commissioned photographer but I also never really wanted to spend my days in a classroom. When I was around 23, I just decided one day that even if someone asked me to take a picture of a pile of dog sh*t I would make the best picture I could. The lines are insanely blurred at this juncture in time in the medium between what is commercial and what is art. It's really up to each individual to determine how to combine the two. The most important thing though is to have a voice that is yours and both sides of the industry will reward that commitment.

For me, the crossover comes in the discipline. No matter what, I believe you have to create something special each day and there are no excuses. I like that challenge and I think it's healthy for my process as a whole.

AJ: Is it hard to balance commercial work and personal projects? Or do the two overlap?

CC: The balance is tough but probably not too different than someone who teaches and tries to make fine art work. Time will always have to be managed and juggled. Mix in kids and family and it all gets fairly hectic. I sincerely believe that most artists make the best work of their careers at the beginning just because they have time and no money. It just gives you space to think.

There really isn't any overlap for me in a tangible way because the content is so different. However, the intangibles are huge. If what you are doing personally is really good, then a photo editor or art director will find a way to collaborate with you. When that happens, you will arrive on your own terms, not because you have emulated someone else's style or technique. Especially nowadays when there are so many people with cameras that the word authenticity really does matter.

AJ: I know you shoot an 8x10 view camera. Do you use this for your commercial work ever or is this strictly for your personal work?

CC: At times I have used it for my commercial work. The truth is that film is expensive and labor intensive. Most people are on deadline and the newer medium format digital backs are pretty amazing when it comes to printing in a publication or looking on a screen, which is how most of us view the greatest percentage of images these days. Although, for actually making an object, you can't beat the big film.

AJ: I have to ask it: do you prefer film or digital photography? Do you find yourself shooting differently when you've got a film camera?

CC: They are just different and I really enjoy both. Digital photography, at its best, is really astounding and an extraordinary tool to have. You can explore more with what you're photographing, and the controls that you have to adjust images are incredible. It does, however, have this homogenized flatness that feels machined which you have to be able to get past.

Film on the other hand has depth and intention, and while you aren't going to explore as much (make as many exposures), the one gem that you get is usually much more considered. It is expensive though and time consuming. In a time when people's expectations are a million images and books every year by the same artist, it may be less culturally relevant.

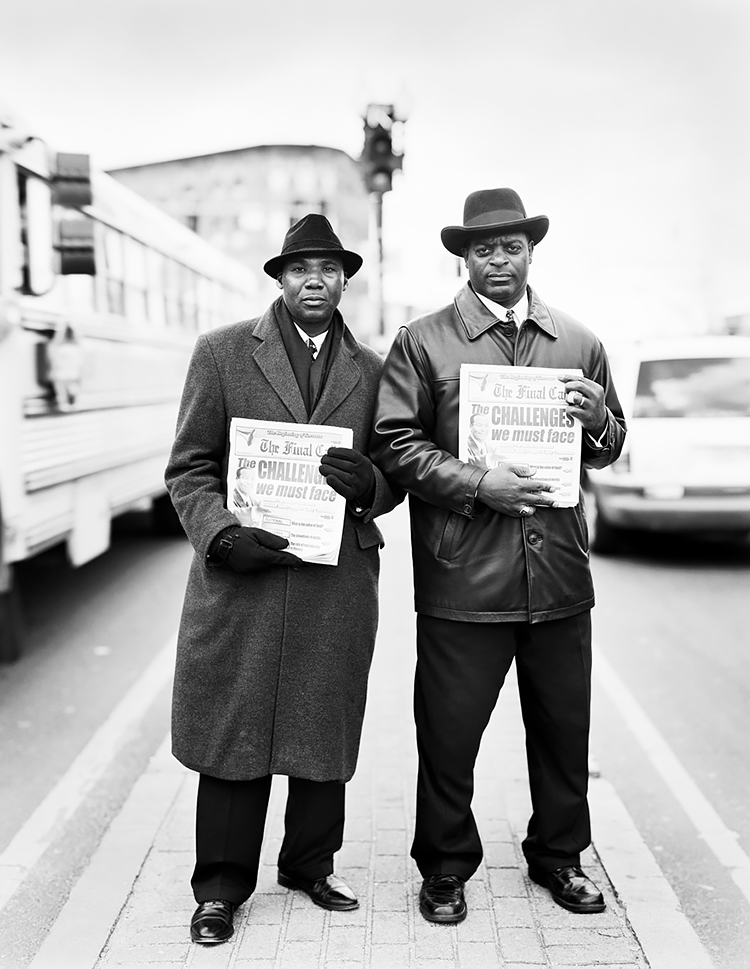

AJ: How did your first monograph, American Faith, become a reality? Can you tell us about the evolution of the work as well as the ultimate creation of the book?

CC: The project was made over 7 years and, as in most personal endeavors, the direction of the work lead itself. It was 7 years of a really special conversation with photography. I think the images, in some ways, are transcendent, and are some of the most powerful that I've made in my career.

As I was working on American Faith, I showed the project to as many people as possible and entered as many competitions as I thought would be appropriate. One of those was The Joy of Giving Something which was founded and run by the late Howard Stein. The director, Peter Farhni took a liking to the work and offered to help. I went to Howard's place and we all sat down; I showed them prints and he got up and said We'll be in touch. The next day Peter called and said Nazraeli Press will publish the book and Howard will pay for it. It was really quite amazing. To that note I think if we can whole-heartedly apply our skills and effort to projects larger then ourselves that have meaning beyond our own interest, other people will want to be a part of that too.

AJ: Can you tell us about current projects you are working on?

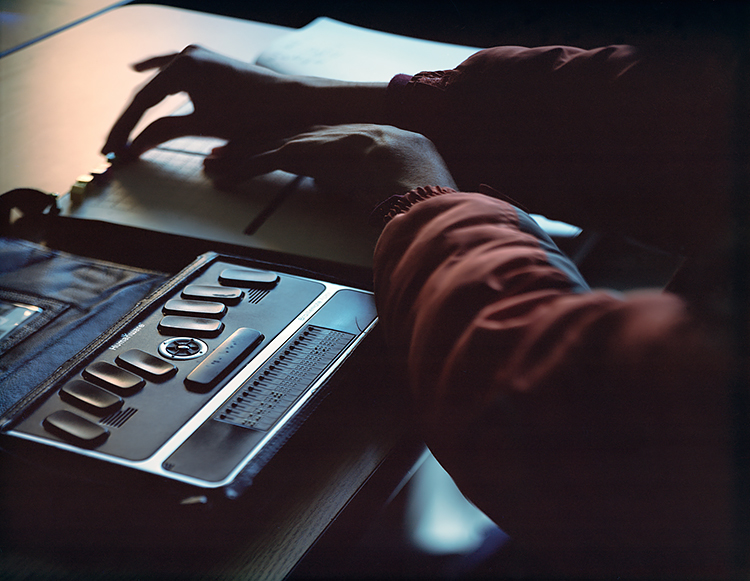

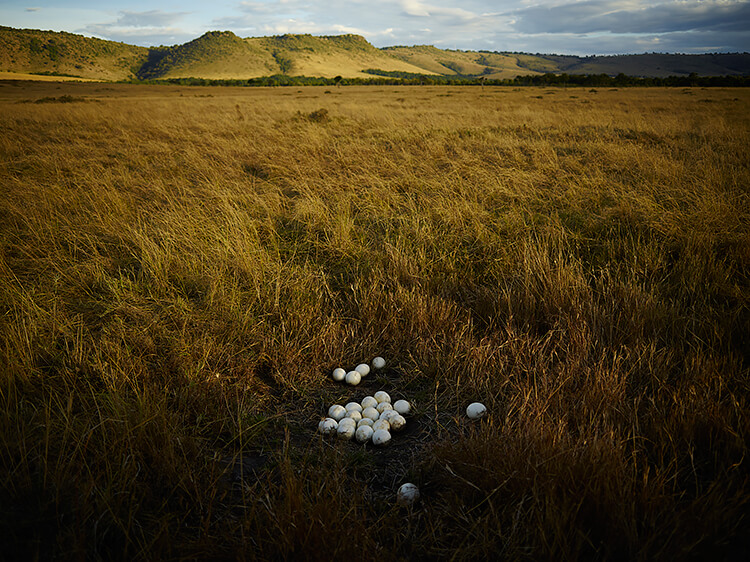

CC: I'm currently working on a series at The Perkins School for the Blind in Massachusetts and another slowly developing project called Populous. The two are at opposite ends of the spectrum with Perkins being about disability, youth, cultural stigma, and I'm hoping to give exposure and a voice to that population. While Populous is about veneer, capitalism and the landscape of American apathy.

AJ: What is the Perkins School and what are your hopes for the project?

CC: Perkins is one of the oldest schools in the country (and possibly the world) for the blind. Helen Keller attended and the school is at the forefront of thinking about blindness and disabilities. The students come from all over and it offers them an education that the public system can't deliver. My ambition at this point is to make great images and elevate the work beyond myself to create insight and meaning for others to interact with it. I hope the outlets for that would be in museums, festivals, magazines and perhaps a gallery show if it is a good fit.

AJ: What challenges are you facing with this project?

CC: One of my favorite things in working on a long term project is the interaction with strangers. Because the kids are in school, they are really busy or, if they are severely disabled, they are unable to have any interaction. It has been really difficult to try and find meaning in those two situations: one doesn't allow time and the other doesn't allow for communication. It's been very challenging, but probably like the kids who attend the school, progress has been slow but important.

AJ: Do you ever attend various portfolio reviews or photography festivals? Do you find them helpful?

CC: I attended the PhotoLucida review on a scholarship which was immensely helpful to my career. I came with a very realized body of work which I think is important for any photographer attending a review. It was more a time to share the work with a larger audience than necessarily looking for feedback.

As for festivals I've participated in a few and would love to do more of them. With their prevalence throughout the world and the global phenomenon of interest in photography I think they may actually be one of the most important and relevant ways to see work. They exist in a temporal way that museums can't and without the economic pressures that I find palpable in commercial galleries.

AJ: What is on the horizon for you as a photographer?

CC: Certainly making progress on the Perkins project and Populous is a huge priority. Other than that, I never really know, which is the beauty of this career.

AJ: What drives you to do this work?

CC: There are so many reasons. Most importantly I hope the work I make can offer the people who view it a space for themselves to better understand the human condition and the society we live in. I treasure having meaningful exchanges with strangers. I love the wandering, the solitude, and beauty of the world and being able to explore that is just such an amazing privilege. I love the chase of getting work. I love the people I work with. One of my favorite things though is bearing witness to the dialogue that forms between photographs. Seeing the photographs take on their own life and meaning that was once rooted in one's subconscious efforts but then grows to be something much different, that it ends up teaching you something new about yourself and the world around you. That dialogue is so important and special.

AJ: What advice to you have for emerging photographers?

CC: Follow and explore your interest to get something started but understand that no one really cares. In other words, no one cares what kind of music you play, it's how you play it. Learning to play takes time. Lee Friedlander met Elisabeth Sussman when he was thirty; it took him 30 years to then get a solo show at the Whitney. It probably took him 30 years to fully realize his work and her 30 years to really understand its complexities. It all takes time and you're not that important. What is important are the pictures and the conversations your photographs have with the people who view them.