''...the beauty of the imperfect, the impermanent, and the incomplete... and the joy found in the ordinary and the mundane...''

– Wabi-Sabi (Traditional Japanese Aesthetics)

THINK POINT, my son's coin, is, unequivocally and appropriately, a place where our thoughts would tide if we looked out at the expanse of

the heaving and flickering Pacific fathoms. It's his personal resort, a pressure release valve from the demands of his warship nearby. A spear of

land at the eastern edge of the Yokosuka harbor, virtually a stone's throw from Tokyo Bay, overlooking the highly secured U.S. Navy's Seventh

fleet docks. There, a small squadron of hawks roosted, keeping watch over the proceedings. It was not lost on us that we both were not far from

where Commodore Matthew Perry had landed with his four ships in July of 1853 – referred to in history as the “Opening of Japan to the

West.” At that very moment, one of the hawks took off and headed west over the bay, by flying east.

The land of the rising sun is better phrased as the land of the searing sun – that had me scurrying for the shadows, whenever opportunity presented itself,

which the Japanese aesthetic savant,

Junichiro Tanizaki (1885-1965) had so eloquently consecrated in his classic,

'In Praise of Shadows.' This

experience had triggered my boyhood images of the Kimono clad Japanese dolls with their exotic folding fans, which I thought, for a considerable length

of time, a fashion accessory, that is, till I happened to be under their sun. Their flag, a minimalist symbol, is the perfect representation of this

phenomenon, as well as the aesthetic orientation of this astonishing nation. It's a place of dichotomous duality that pulls in the opposite extremes – rooted

in deep traditions offset by open and unbridled modernism.

This is hardly a land of rolling fragrant meadows or dulcet valleys, but a mountainous and rocky landscape of dense subtropical undergrowth. Contrary to

the conventional wisdom and notions of beauty, it's not the landscape that makes Japan beautiful, but what the people did with it, in their myriad ancient

aesthetic disciplines. It's a harsh landscape rendered romantic by

Edo's Katsushika Hokusai's (1760-1849) imagination. This reminds of me of the Italians

and the Israelis, who had turned a lime stone peninsula as the seat of the most awesome empire in history and now the many empires of its various

brands, and a desert flowing with orchards, water and technologies. So did the Japanese, taming the unstable land with virtually no resources into a

fountain of productivity and a haven for its nearly one-hundred-twenty-five million citizens. It's beautiful, by virtue of its people and their sensibilities –

an extremely rare club to be in.

How does one really evaluate any super-culture, by their mega-industrial edifices, or by the small things everyday that are mundane? Ordinariness as

opposed to the extraordinary is never ascertained or gauged by the scale of anything, but by the smallest of details and the condition it effects. People are,

never really affected by the scale of projects at a personal level, other than the momentary initial wonder or surprise, like they are usually with beauty in

small details that bring joy to their convoluted and weary existence. Incidentally, hygiene is not just a precautionary concept here, it is an aesthetic one if

one can flush out the stale thinking. Aesthetic is the spiritual factor that underlies every endeavor, material and immaterial. Beauty is the central value in everything that adjudicates something as a success or a failure. And, the Japanese have rendered every aspect of their life into an art form over the

centuries, a singular phenomenon that I had witnessed only in Italy, and to a certain extent in France.

The Japanese are the most ancient society whose pivotal operating principle, at all levels, had always been aesthetic: a composite and or interconnected

variances of beauty replete in nature are woven carefully into their daily rituals – to be one with the spirit of nature. The idea of integrative beauty, natural

and or mimed, as instituted by various national and cultural concepts had emanated off various strains of Buddhism, Shinto, arguably being distinct. The

Zen and Wabi-Sabi precepts profess that beauty is the predominant spirit of nature, and in our understanding of its austerity, restraint, ephemerality,

imperfection, decay and most significantly, transformation, we consecrate it. And, by incorporating such aspects in our lives, we become one with it.

Aesthetic is the spiritual gravity of everything to the Japanese, as in Shinto's

Kami, in the divinity or spirit of everything. And it's as if every generation in

Japan, from the mid 19th century onward, had somehow known Friedrich Schiller's

'On the Aesthetic Education of Man.'

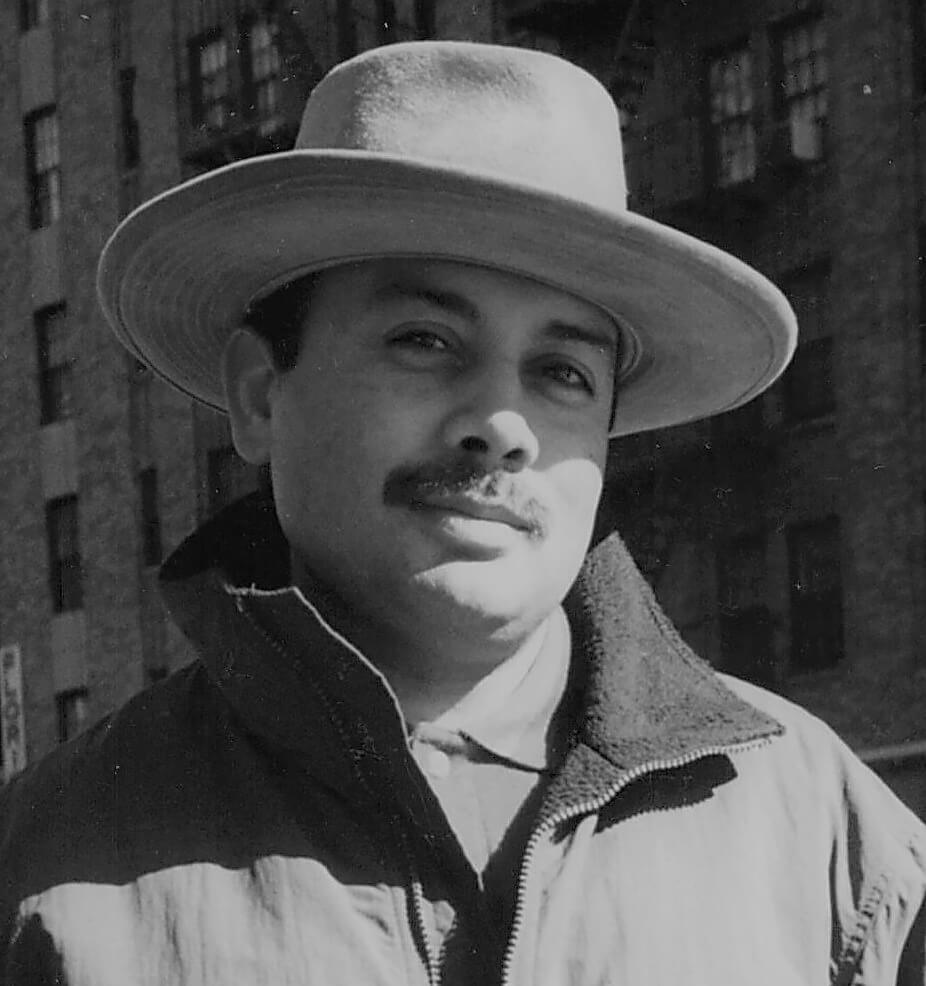

July 18, 2024: Five-Hundred-forty-eight days had elapsed since I had seen my older son, who had left us as a mysterious chrysalis, and in the ensuing

years had emerged as a hardy adventurer, one from a warship of the U.S. Navy's seventh Fleet. And since all good things in my life have been a direct

consequence of being with my son(s), this year-and-a-half gap was weary on me. As with anything, the pleasure of having fun with an offspring really

starts with their toilet. And ironically, as soon as I had arrived at Haneda airport, my pleasure had commenced with my toilet. It was there that I had the

visual evidence on the maturity of Japan's super-culture, and the pleasure it would yield along with my son. Few things are as revealing about a society as

its public conveniences – the most basic fundamental functional condition of any society is the riddance of its waste in the most expediently aesthetic and

hygienic manner.

As we sped towards the Yokosuka Naval base in our taxi, both sides of highway were stacked and packed densely with contiguous industrial

superstructures in grays and pale yellow. Large buildings connected to small and large tanks with crisscrossing pipes in every diameter in every direction,

hovered over by the Sumitomo cranes everywhere made for a mesmerizing steam punk aesthetic, it had that HR Giger like intensity. Halfway to our

destination, the dense industrial jungle tapered off into a dense verdant undergrowth towards the sea and the base. We did not go into the Naval base that

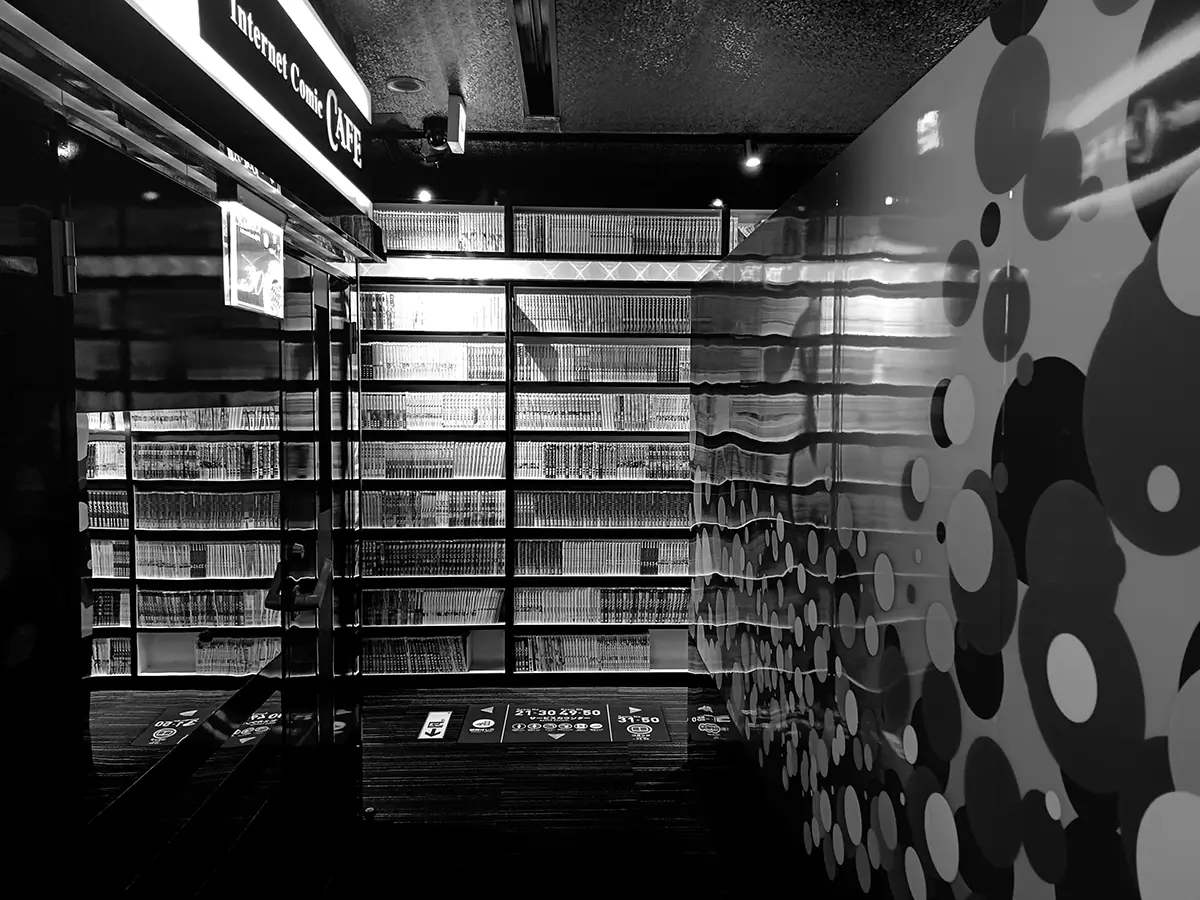

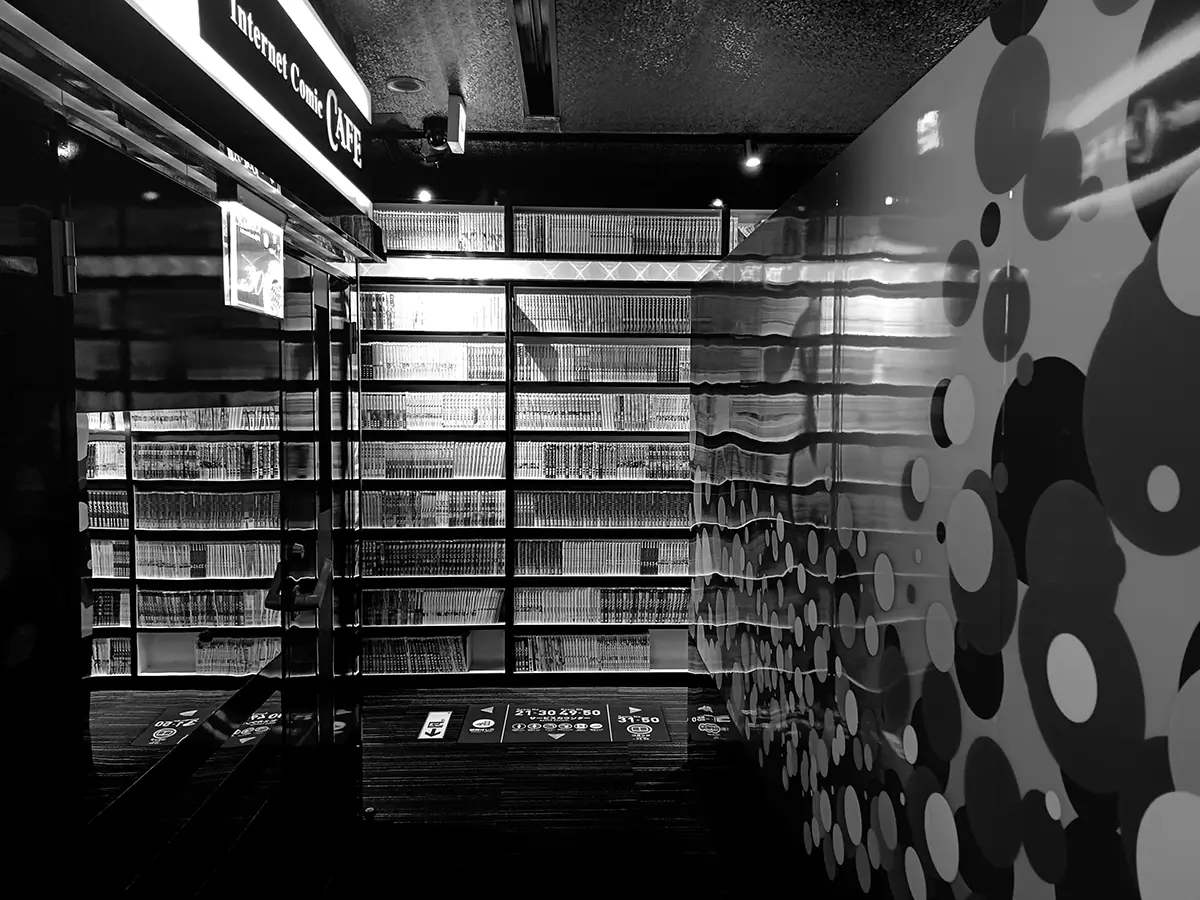

afternoon, rather, my son lodged us at the internet cafe in the city of Yokosuka: Manboo, at the Mikasa shopping plaza. It was a “Blade Runner” like

setting, with small avante-garde rooms where one gamed 24/7 in darkness with flat screens and high powered gaming consoles. For the keyboard

exhausted, and for the tactile and the anachronistic, there were thousands of neat acrylic covered Manga graphic library.

The Japanese are a visually savvy graphic culture. Their visual sophistication is represented in their incredible anime (Animation) which are hand-drawn

stories in the form of Manga graphic novels or films and videos. They exquisitely render even the most difficult psychological, social, spiritual and

natural issues into gripping graphic mediums. Incidentally, Japan hosts the world's most aesthetically charged porn industry, in anime form, known as

“Hentai.” It is, unequivocally an art form in the rendering of both the genders in our most natural function, with a huge following everywhere. However,

the maestro that sits atop their Anime Mt. Olympus is none other than Hayao Miyazaki, whose many creations like

'Spirited Away' are literally

worshiped by both children and adults. The internet cafe room was about 7x6 feet, and this proximity to my boy reminded me of the time when we would

watch

'Princess Mononoke' several times in a row with him on my lap.

Internet Cafe © Raju Peddada

Manga Library © Raju Peddada

The next day, his casual understated declaration of the two-plus kilometers proximity of the Navy Lodge from the main gate of the

Naval base and our ensuing walk felt like a trek from Agadez to Bilma, in Niger, only in ninety percent humidity. I got caked and baked, he didn't break a

sweat. We were walking south within the base after leaving the town of Yokosuka, and all around us were the Naval activities buildings in pale yellow,

white or light gray in that harsh sunlight. Then a kilometer in to our left, the piers started with naval vessels, gray numbered warships bristling with weapons and other sinister protrusions, under huge cranes. A surreal panorama that no civilian has access to. The piers and the dry docks were flanked

with industrial sheds on either side where all the ship parts were manufactured. No waiting and no shipping – from the sheds to the ships.

On the way to the Navy Lodge, despite being in an outdoor oven, we found distractions that helped us escape it: beautiful manhole covers, each identified

by symbol and color, then the beautifully sculptured the trees, like gigantic Bonsai, and the big rock faces, as depicted in their ancient paintings, abutting

the road were drilled with holes to release the pressure of downpours – and the relentlessly dense plants taking root in almost every hole and crevice. We

also eventually found our refuge at the Navy Lodge, which belied the luxury we found ourselves in, designed and built by the host society. Again, I found

brilliance in the design and application of daily fixtures, use of space, adaptation to the environment and its preservation, preparation for emergencies,

and infinitely pleasant the service. At the lodge check in, the beautiful Japanese lady hands back my credit card and the door keys with both hands

extended accompanied by a gracious bow with a smile. Her little gesture lingered in me like some mysterious atavistic spice for a while. Even the minor

act of giving back of the cards to the customer was a movement with sublime beauty. Why can't we have this back home? I had asked my son.

The next day we had a McDonald's breakfast on the bay, and I had gladly relived the same service with the dulcet Japanese girls there. Later, we went

exploring around the base, and my son had used this pretext to quietly take me to his personal resort, “Think Point,” his place for depressurization and

contemplation. Later in the day, while he gamed in the room, I had used the little kitchenette to cook his favorite entree, called “Puri.” Earlier, during our

foraging excursion into Yokosuka, what I found was yet another proof of their visual finesse, beautifully wrought signage by the stores, nothing

incoherent, but everything fundamentally within the graphic maxims. How is it possible that even a small independent vegetable seller is so visually

savvy?

Manhole Art © Raju Peddada

Giant Bonsai © Raju Peddada

Our destination was Tokyo. It was a late start at the Yokosuka railway station. Their trains system is simply the world's most advanced. It's

a three tiered system, the first being for the local stops, the second as the inter-regional or neighborhoods, and the third, their famous Shinkansen, the

bullet train, which was the blistering-paced inter-city system. The tickets acquisition for us was a complex, irritating and frictional proposition since the

directions were all in Japanese. In other words, one cannot wing it, but, we eventually got on the right platform, thanks to an English speaking local lady.

The trains were fast, efficient, and utterly clean. No teen gangs, no homeless sleepers, and no panhandlers and definitely no altercations. Everyone

appeared affluent, working class, and kept to themselves. It was a thrill to observe this unique setting and the blurring neighborhoods on the hills through

the train windows. It was almost lunch time by the time we had arrived in Tokyo – a clean megalopolis of thirty-seven million, ten times more dense than

Chicago.

We both took a jaw-dropping one-plus hour double-deck bus tour around the city. It was only way to gauge the magnificence of this sprawling marvel.

Their spiffy space savvy vehicles on the roads were design delights, as they looked like cameras with windshields on wheels. And speaking of traffic, no

blaring sirens every other minute, for whatever reason. Since the 1950s, Japanese life had flown into rapid urbanization with several thousand square

kilometers of apartment buildings. The concept of “Zenimalism” took hold in those years as spatial challenges induced the Japanese to create peace and

tranquility in simple soothing shapes and soft colors in natural materials. Eclecticism took hold in architecture and some practitioners experimented in

unorthodox forms, the foremost practitioners were Shin Takamatsu and Tadao Ando. There are more Japanese architects percapita than anywhere in the

world, and humble residences became the prime commissions for new forms. Incidentally, our lunch was an ancient form practiced by an intrepid

Japanese kitchen in Ginza: Neapolitan Pizza. On the way back my son surfed on his phone, while I dwelt on my dwindling time with him in melancholy,

despite all the distractions.

In the morning on Monday, he had slept in, while I convulsed in the kitchenette to prepare his favorite meal, referred to as “Chole Batura,” – an ancient Indian recipe from the Himalayan hills with an entree made of Chick-peas in spices, and deep fried bread from pizza flour yeastraised

overnight, a family favorite. In the aftermath of a satisfying lunch our cold room became a refuge after getting toasted in Tokyo. He gamed, while I

sketched out this article, struggling for the perspective – then it arrived, in the mental image of the hawk returning: my son, the trip for him, and Japan

with its unfathomable culture was all about transformation, that inexorable aspect of life.

After the dark ages (Middle Ages, from 5th through the 13th centuries in Europe), there emerged several transient lifestyle movements starting with the

Renaissance, followed by the age of enlightenment. The Baroque excesses tapered off into the Victorian repression. Then the early 20th century stirring of

the western geometric austerity: Weimar's Bauhaus movement, and its parallel, Soviet Constructivism, all vanished with the advent of the Nazis. After the

WWII, there emerged the Western post-modern minimalism in the 1950s, perhaps derived from Japan. However, the Japanese minimalism as a way of

life is over a millennia old, not as the indulgence of the affluent or the consequence of human intervention in material or immaterial tastes, but rather their

recognition filtered throug ancient Shinto precepts of adaptation, preservation and consecration of nature's transient, austere and asymmetric beauty in

decay – their supreme guide.

Whether it's Edo's evolution to Tokyo, Shinsaku Hamada's iridescent glazes, Junichiro Tanazaki's consecration of the shadows, the Shoji screens

modulating light, the spirit of Shokunin (the artisan) or the ancient Ikebana (floral arrangements), or their ancient Shuji (calligraphy), the street

photography of Daido Moriyama or their sublime women – it's all about transformation. All these profound concepts had cued me in on how my son, that

mysterious chrysalis that had left us in 2020, was transformed into this man, in the illumination of his eyes when he saw me at the airport. His nascent

facial hair that signaled his manhood, the hardy callouses on his fingers that had replaced his innocent chubby hands, that familiar lopsided smile from his

boyhood to that complicit smirk now – and, his various physical mannerisms imprinted and sedimented on my psyche as well as my subconscious like

the treasure maps of our many excursions, had remained unchanged. To my relief, his understated bearing and dive into serious topics without small talk

was the unequivocal assurance that in all those sea of changes, he was absolutely the same. I was content. And after less an than a week with him, and

still in this state, Japan and my boy's resplendence got amplified as I drifted into a sweet slumber in that white noise of my flight to Chicago.

Traditional Sushi © Raju Peddada

Mother and Daughter Beauties © Raju Peddada

Stylish Brothal © Raju Peddada

Betty Boop lost in Japan © Raju Peddada