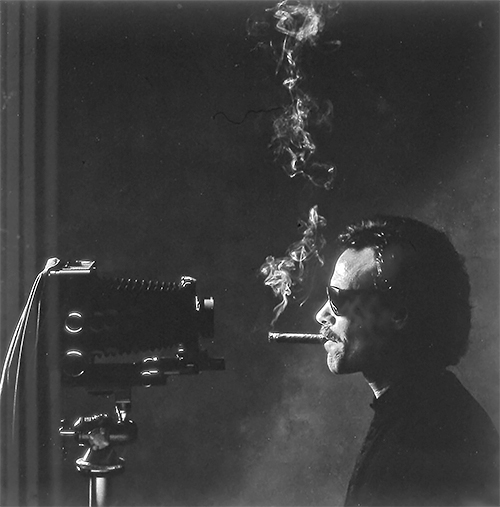

Not as many photographers

load cameras anymore, but we all still

aim them and

shoot pictures. You might say, I get a bang out of describing my own photographic pursuit as hunting for big

game, portraits in particular. I bag my quarry with a four-by-five instead of a thirty-aught-six.

But I still hang their heads on a wall to admire like trophies

The memorialization of a deliberate encounter with a human being — in one shot, so to

speak — epitomizes the hunt. When it goes well, it’s because the subject has allowed me to

reveal something personal within a two-dimensional frame, a graphically compelling

composition embellished with shadow and light — sometimes color, too. The late, great Arnold

Newman summed up all the hard work with his quip: “Photography is ten percent inspiration and

ninety percent moving furniture.” It’s now an insiders’ cliché, but I remember laughing out loud

when he said it to me personally, decades ago. It still brings on a smile after every exhausting

shoot. I’ll add that, despite one’s best attempts to prepare in advance, any photoshoot can go

sideways and, like a MacGyver episode, it becomes necessary to solve a cascade of unexpected

trials involving lenses, lights, cameras, props, wardrobe, location, deadlines, weather,

temperament . . .

furniture. Sometimes the big one gets away.

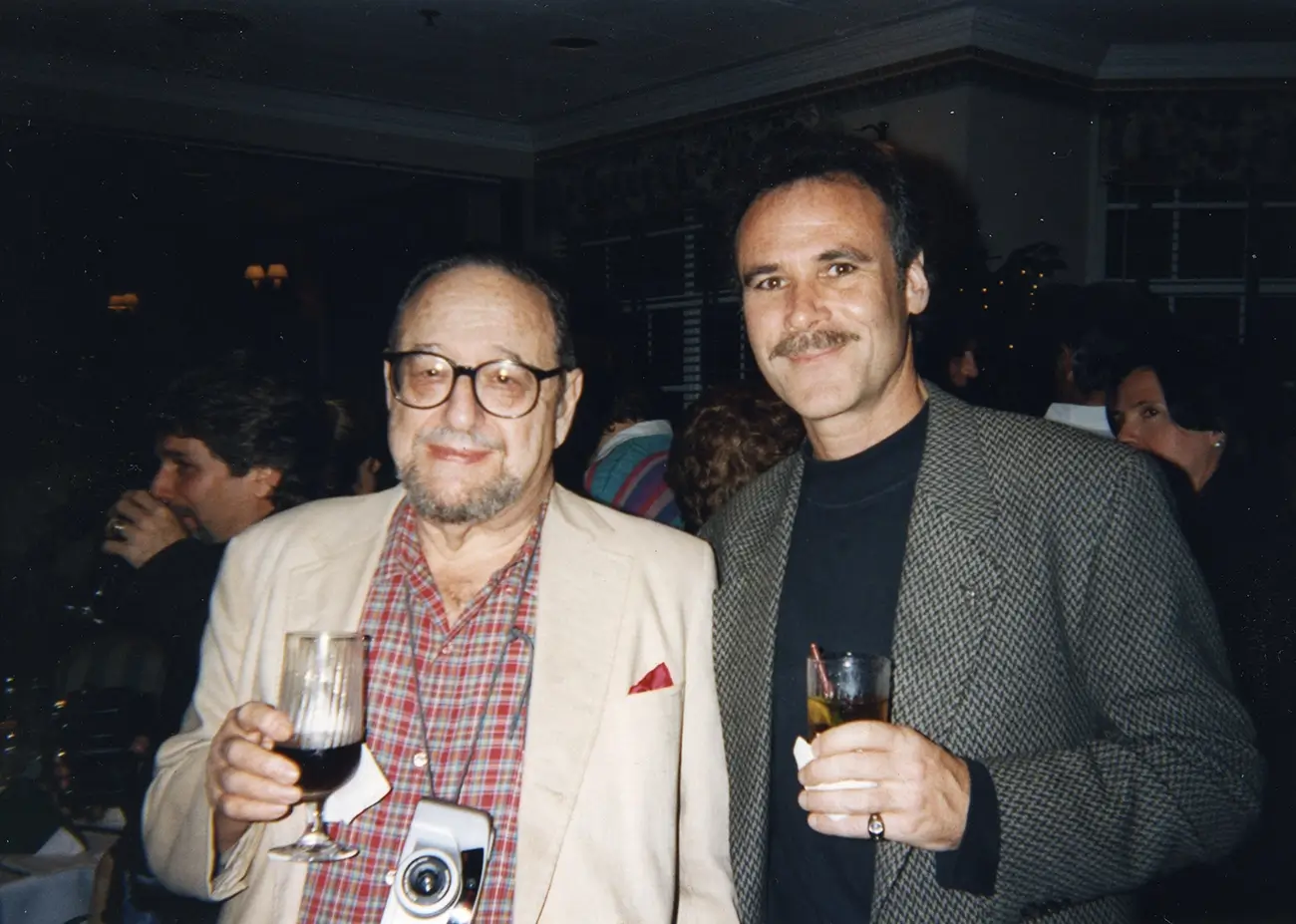

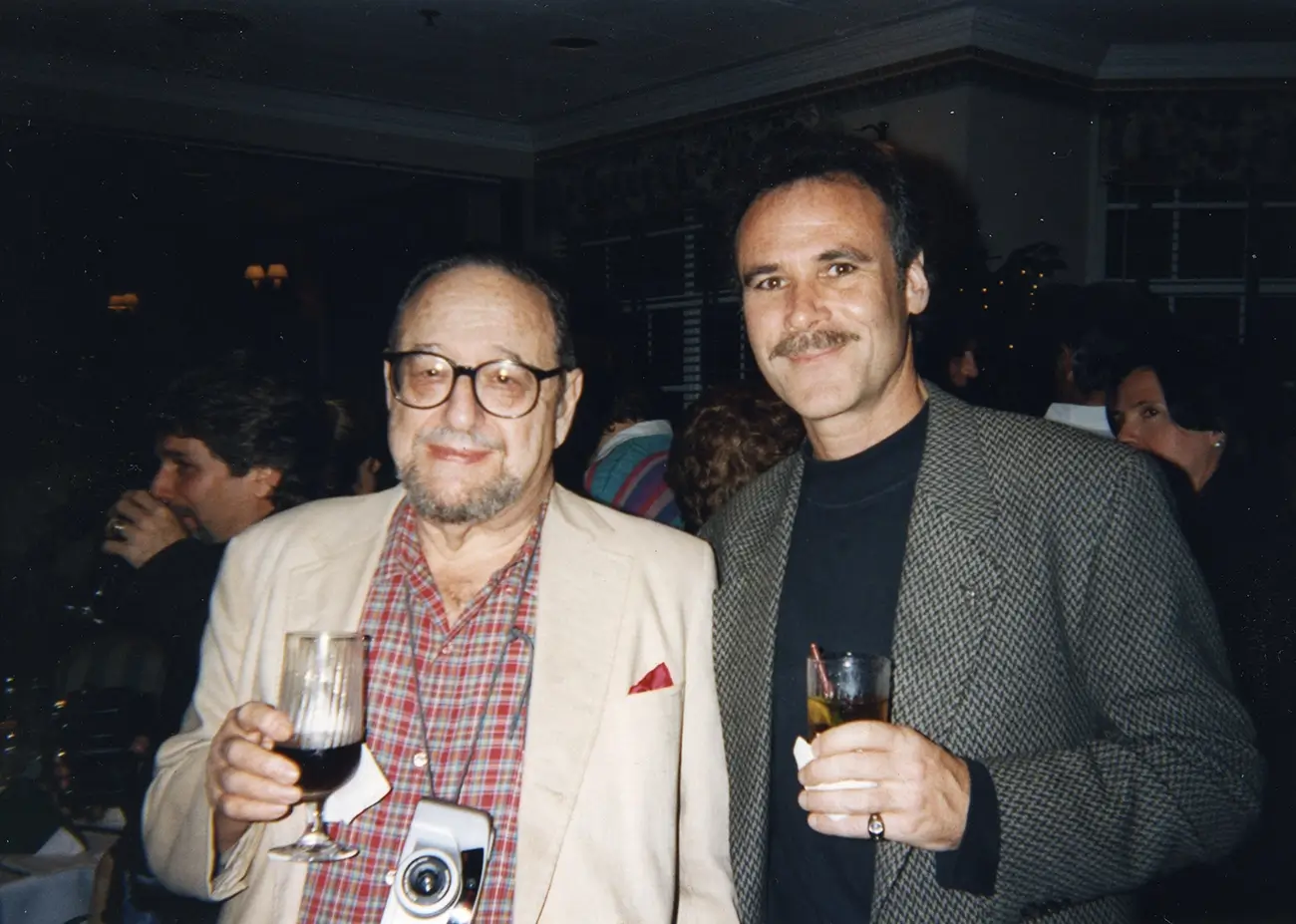

Arnold Newman and Tom Zimberoff

More than illustrations of interesting people or handsome faces, portraiture is about making

visual allusions to character with artistic integrity. An adept portrait photographer tries to show

as much about what someone does, often vocationally, as much as who they are personally. To a

lesser extent, a portrait may say something about the photographer’s relationship with the

subject. Ultimately, however, that relationship is the photograph. Nothing more. Nothing less.

Only rarely does a lasting personal relationship ensue. But always, a record remains of what they

saw, looking at each other, or at what it was agreed should hold the subject’s gaze. It is that

moment, frozen in time, when the camera becomes a surrogate for either one viewer or a large

audience.

Looking at a photographic portrait is a kind of hack of human psychology because you

can stare right into someone’s eyes with no compulsion to flinch and look away. It is also crucial

to recognize how inescapable it is to form an idea about what the subject of a portrait is thinking

or feeling, even though that person (or persons) is observed neither in real-time nor moving

about in the real world. And don’t miss the irony of losing your sense of self in this condition,

looking closely and intimately at someone else. It is an experience of becoming self-effaced

while looking at someone else’s face. Portraits help us understand that people are always looking

at us and that we are all subject to someone else’s perception.

Today, everyone has a camera. We all take pictures. We’ve all had our picture taken, often

with family and friends. We’ve all got our selfie faces now, too. But the experience of being

portrayed can hardly be taken for granted. It is an act of total engagement, usually with a

stranger. The photographer is the stranger.

Not as many people as you might think have been invited to experience a photographer’s

punctilious attention. But we all know how uncomfortable it is to take direction, to be manipulated

into a pose. It is even more unnerving to be stared at through a lens. You are precisely the subject of

attention, sometimes in an alien environment: a forest of light stands, cables, umbrellas, gobos,

cucolorises, snoots, booms, and barndoors . . . flinching at the loud pop and bright flash of strobes.

It’s possible to encounter production stylists, photo assistants, and art directors hovering about, too.

(You may be the subject but you’re treated like an object.) Nonetheless, even with no more than a

camera on a tripod, whether shooting outdoors with only sunlight and shade or indoors with light

coming through a window, every successful portrait is contrived — in the best sense of the word.

Portraiture is a collaborative effort executed with deliberation and care. It takes time You

can’t

take a portrait: a portrait is

made. Otherwise, it’s merely a snapshot.

Because

snapshot can sound dismissive, I'll use

candid. Too often, I’ve seen how

candidly-captured photographs — irrespective of artistic merit but just because people are

included in the composition — have been carelessly categorized as portraits by influential people.

If such a photograph is, for example, excerpted from a documentary project that features people

occasionally glancing at the camera or making deliberate eye contact with the photographer’s

lens, the distinction between documentary photography and portraiture is muddled to the

detriment of both genres. My point is, the notion of a spontaneous, unplanned, or unstructured

portrait — a “candid portrait” — is an oxymoron. Portraiture is a very specific discipline. It is an

art form, not a format.

Portraits include candid likenesses, of course, but in the context of

candid

meaning honest and sincere, which includes unexpected mannerisms and expressions. We take advantage

of spontaneity but we do not capture anyone’s likeness surreptitiously; our subjects participate

knowingly. And there’s planning, a prerequisite for any photograph worthy of being called a

portrait. While serendipity adds magic, it is incidental to the conceptual rigor that goes into a

telling portrait, the ideas thought out long before a camera is brought to a photographer’s eye.

This is not semantic nitpicking. Conflating candid photos with portraits diminishes the

legacies of

August Sander, Arnold Newman,

Richard Avedon, Irving Penn,

Yousuf Karsh,

Philippe Halsman, et al. . . . plus many more contemporary portrait artists. Though we welcome

evolving photographic styles, there is a difference between style and substance. I’m not the portrait police, but misclassifying the essential properties of portraiture confuses its conceptual

integrity vis-à-vis other photographic genres. It causes confusion. For instance, conflating

documentary projects (pursuing an agenda) and also photojournalistic reportage (bearing witness

to events) with portraiture allows the advocacy of political or societal issues to creep insidiously

closer to taking precedence over the quality of photographic execution and its expression as

portraiture. If the content depicted in any given photograph takes precedence over the intrinsic

quality of the photograph itself, is that art?

Lately, I’ve witnessed an increase of inaccurate information that has spread like a game

of telephone from one academic institution to another, or from one curator to another, until what

was once “this” has becomes “that” within their insular world. Thus calcified into flawed

doctrine, this misinformation perpetuates institutional biases and leads to a homogenization of

artistic standards and institutional memory loss — call it photographic memory loss if you will.

I recently attended a photo symposium populated with several dozens of gallerists,

curators, and photographers, many of them anointed with MFA degrees from Ivy League

colleges, who couldn’t recognize the names of at least a dozen influential photographers included

in the fine-art photography canon. These MFA photographers were at a loss to either recognize or

describe photographic techniques that have been commonplace for decades. I think the internet is

largely to blame, as it is too often relied on as the ultimate authority for professional inquiries,

even by some academics who have apparently been unwilling to perform their own due diligence

about the sources of the websites they’ve queried, having yet to learn that the presence of a

website should not be mistaken for its plausibility.

Despite being sharply focused, well-exposed, and adequately composed, many pictures of people

are souvenirs made on the fly by camera enthusiasts and tourists. Did the photographer really

take the picture, an act of theft? Or did the subject acknowledge the taking (away) of it?

Awareness notwithstanding, was there consent? Photojournalists, I concede, will and must

include stereotypical depictions in their reportage, but these will only be grace notes to

complement a larger set of pictures that, when well-edited, tell a broader story. When seen on

their own, however, do such photographs truly exhibit the hallmarks of a portrait? Personally, I

don’t think so.

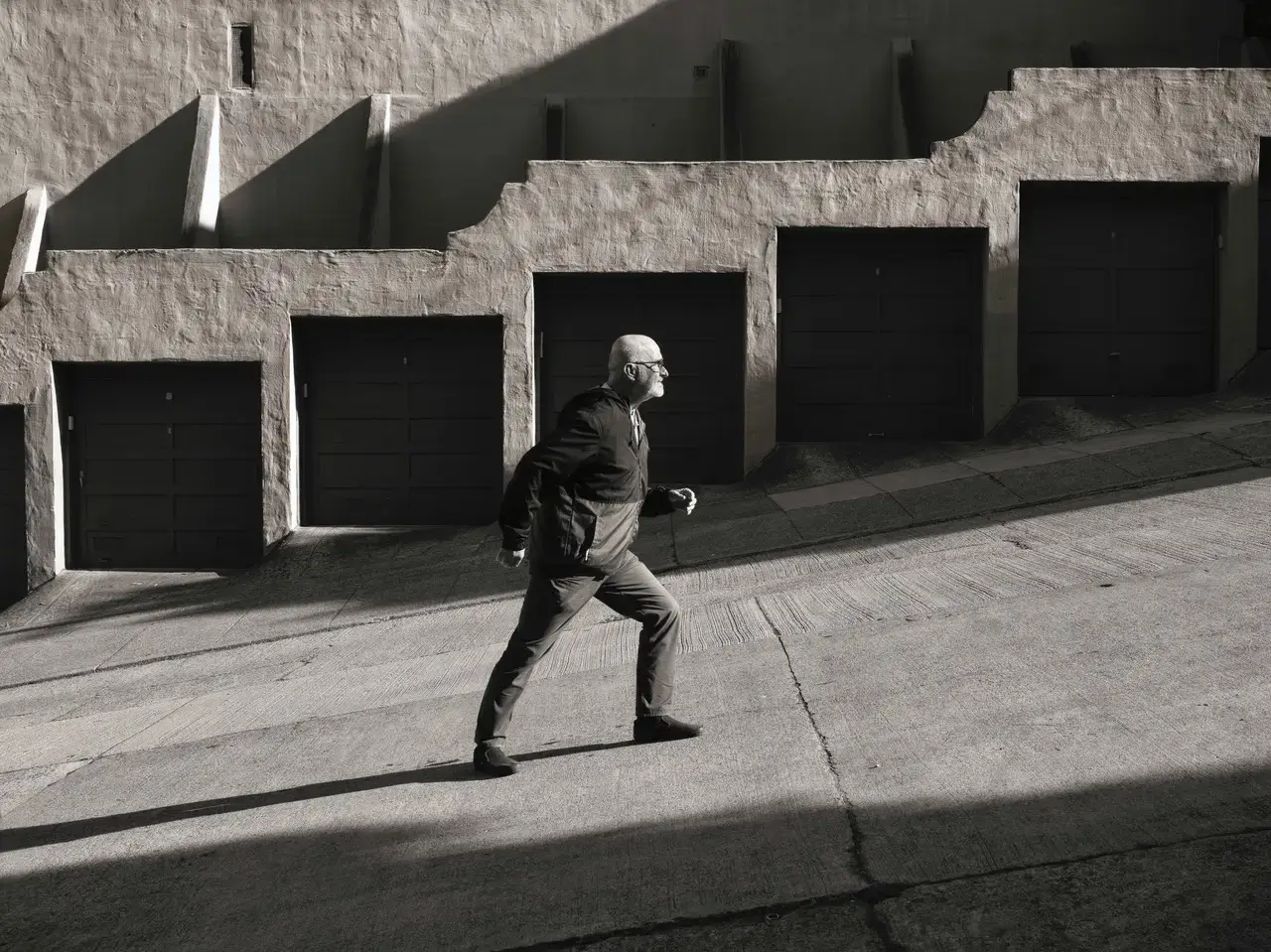

Edwin Outwater © Tom Zimberoff

To be considered a portrait, a photograph should be more than an agreeable or photogenic likeness of someone. That means a depiction should be more than superficial; it should dramatize one aspect or another of its subject’s persona by telling a story, and the story must be told with concision; and not about something that just happened to that person — because that’s reportage — but about who that person really is. Empathy, too, plays a part. But the concept of a portrait does not include the proselytization of a moralistic message. If an individual photograph is removed from a project to be displayed on its own, irrespective of whether the theme of that series is celebratory or poignant — or moralistic, that example must be able to fly on its own aesthetics. However, with exceptions, any number of ostensible portraits expected to go solo quickly crash land, victims of their own inconsequence when seen out of context.

Whether shot with an iPhone, a $20,000 digital Hasselblad, or an oatmeal box with a

pinhole, a portrait is the result of a photographer’s interaction with a sitter. It is rarely a

photographer’s one-sided depiction because, to one degree or another, it reflects the sitter’s

intellectual participation. It should also be self-evident why it was made, certainly not to recreate

a cliché. In the hands of an artist, even an iPhone or an oatmeal box is a fine tool for creating

portraits — even a self-portrait. Only the result counts, not the kind of camera. The camera is

merely a tool.

The reductive drama conveyed by black-and-white works for many photographers when

character is the essential theme of a portrait, particularly when focused tight on someone’s face.

Color, particularly because it may be complementary if not integral to a composition is not to be

disdained. Besides, it’s usually obvious when something doesn’t look right without color or

looks appreciably better because of it. It is also obvious at the outset, to a practiced pro, which

medium to choose (unless a client makes that decision), although both a color and a black-and-

white version can sometimes be equally compelling.

Sometimes one popular example is consecrated as

the

definitive portrayal of someone or another, as if the photographer knew how to distill and bottle some mythical essence of character. I

don’t buy it. That notion only applies to pictures that agree with what we think we already know

about someone; celebrities, for example. It’s not possible to reveal all of a subject’s life story in one

shot, just one aspect of character in that particular instant. Character is too complex, hardly one-

dimensional or immutable. And no photographer has the preternatural power to evince an entire

range of personality in the wink of a lens. A portrait can, however, achieve iconic status as a “best

portrayal,” powerful enough in its expression of identity to stick and be forever associated with

someone. Yet it illustrates only one aspect of a person’s character at one moment in a lifetime.

Yousuf Karsh’s powerful portrait of a glaring Winston Churchill (because Karsh swiped the cigar

out of his hand) comes to mind. And though one portrait can jumpstart a photographer’s career, I

can’t think of one portrait that has defined a photographer’s career. It takes a lifelong body of work

to do that. The Churchill portrait jumpstarted Karsh’s career, and his subsequent work influenced a

generation of portraitists.

Portrait of Winston Churchill, titled The Roaring Lion, 1941 - Yousuf Karsh. Library and Archives Canada, e010751643 © Yousuf Karsh

Sometimes, whether or not the photographer is pleased with the outcome, sitters will carp, even

if good-naturedly, about how they look. “That’s not me,” they’ll say, or, “I never look good in

pictures.” They may agree it’s a fine photograph, just a bad likeness. There is a technical

explanation for that phenomenon.

Your each and every day begins, and often ends, with staring into a bathroom mirror.

What you see — what you’ve gotten used to seeing — is an optical illusion created by light

bouncing off your face and onto the glass surface of the mirror, then back again. The light travels

measurably twice the distance from your eyes to the mirror, revealing an effect called optical

foreshortening. It changes the apparent distance (your perception) between objects in the

foreground and background relative to where you are standing. Looking at yourself in a mirror is

like seeing yourself through a telephoto lens.

Some people call a telephoto lens a “portrait lens” because it flatters by, well, flattening.

It compresses visual perspective, which means it makes the tip of your nose look closer to your

ears. The effect is subtle, but it’s plain to see in two dimensions (pun intended). Alternatively, if

you are photographed up close with a wide-angle lens, you’ll have a big schnoz and smaller ears,

the way you’d look to someone who got “in your face,” standing nose to nose. It’s not that you

look bad in photos. It’s just that you expect to see something different, more familiar: your

reflection in a mirror.

Incidentally, once, while trying to explain this phenomenon to a sitter, I suffered an

embarrassing but funny moment. It was during a photo shoot with John Dean for Time magazine

to mark the tenth anniversary of the 1972 Watergate break-in. Dean was President Richard

Nixon’s White House lawyer.

Dean was one of those people who expressed displeasure about the way he looked in

photographs. I tried to explain how seeing a photograph of yourself is like hearing a recording of

your voice for the first time; it’s hard to recognize it as your own. When that came out of my

mouth, Dean looked at me as though I had deliberately insulted him. (Good expression, though!)

It was Dean, after all, on the secretly recorded White House tapes, who warned Nixon, “There’s

a cancer on the Presidency.” Seconds later, we both realized my faux pas and had a good laugh.

There’s more. You see your reflection in the mirror backward; it’s flipped, reversed. That,

too, plays tricks on your visual perception, this time with facial symmetry. The camera sees you

the way everybody else does: un-flipped.

The typical quality of bathroom lighting complements the mirror’s cosmetic makeover. It

bounces off walls, ceilings, and countertops or comes through a skylight. Shadows are softened

or altogether absent. The bounced and nearly shadowless quality of light diminishes facial lines

and wrinkles. Sometimes bathroom mirrors are surrounded by soft-white lightbulbs installed to

diffuse the light reaching your eyes. (Imagine a dressing-room vanity designed for makeup

application.) This effect, too, flatters by removing shadows.

Sorry, but the way you look in photos is how you really look! But don’t worry. You’ll

discover the magic in how you become more attractive as your photographs age.

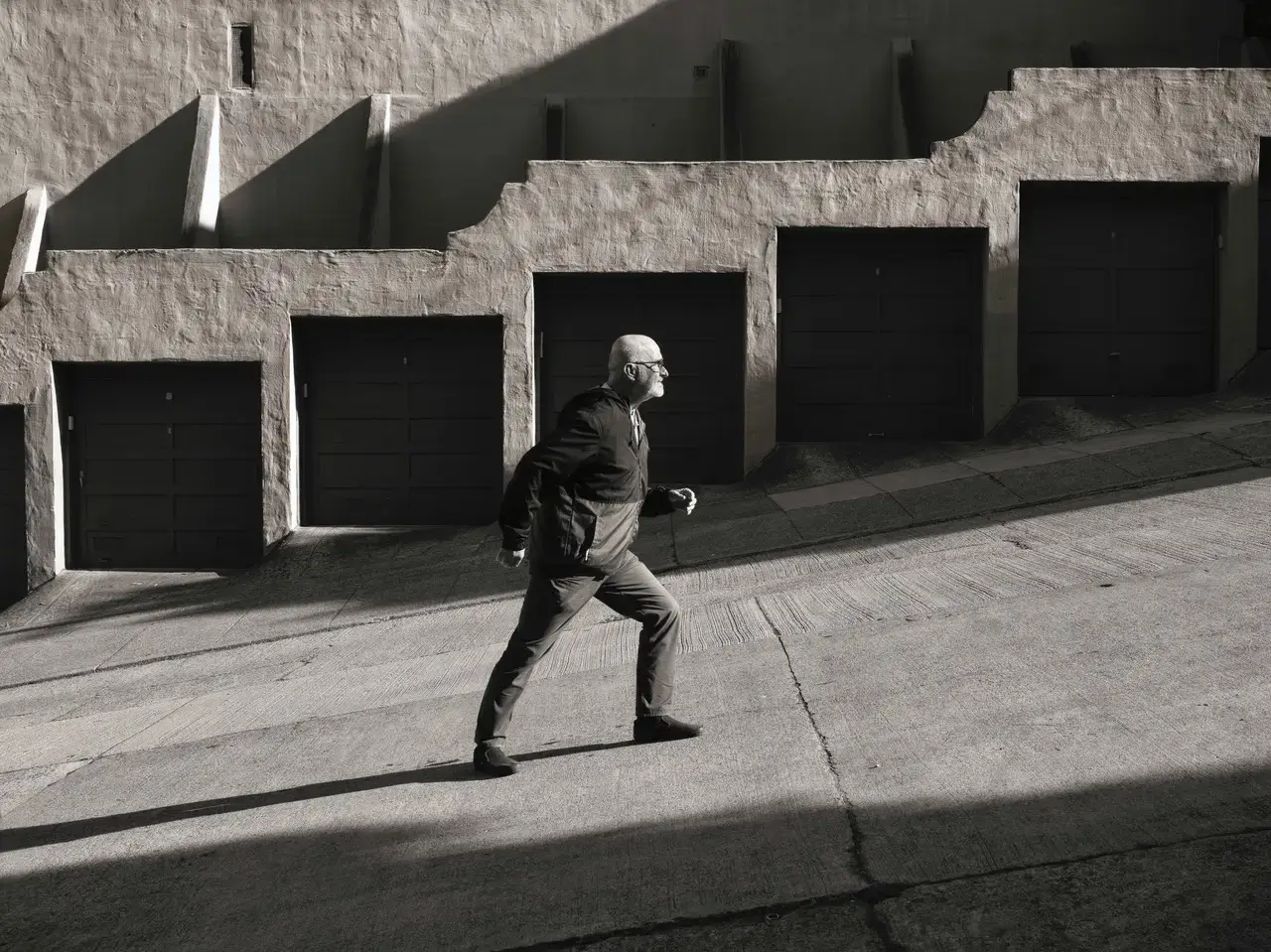

Zeki, Filbert St © Tom Zimberoff

It isn’t unusual to ask sitters to hold uncomfortable poses. (Surely, stretching one’s arm for a

selfie with a self-aggrandizing smile plastered on one’s face can’t be comfortable, either.)

Conscientious portrait photographers seldom ask subjects to strike a pose we haven’t seen them affect on their own. We simply recreate it. That’s why I, for one, do a lot of looking before

shooting. Posing suggestions may seem nutty to the sitter, so I leave them open to discussion.

My posing philosophy goes something like this. If I were to cut one frame from a strip of

movie film, it might show someone taking a step in one direction, an unresolved freeze-frame

captured while moving between point X and point Y with, let’s say, one foot off the ground

accompanied by a head turn. Sure, it will feel awkward to hold still like that, but it can be what

makes or breaks a composition.

No rule says photographers have to make their subjects feel comfortable. We are

sometimes engaged in a subtle game of control versus resistance, sometimes approaching

obstinance, unsure of each other’s motives. Because photographers are ultimately in control,

sitters may feel vulnerable. Therefore, photographers have a responsibility to cultivate trust

without squandering that currency. We won’t allow the distribution or publication of

embarrassing poses — outtakes. But the longer a photographer can cajole the sitter to linger in

front of a lens, the less determined they are to maintain a self-conscious façade.

It’s fanciful to imagine a lens as a sculptor’s chisel, chipping away at the surface to reveal

what lies underneath. I tell sitters that it only takes 1/125th of a second to shoot a picture and that

when we’re no longer having fun, we’re done. But I also try to persuade them that the longer

they stay in front of the camera, the better our results will be. If we’re lucky, the result can

transcend the encounter itself.

On another note, self-portraits notwithstanding, a portrait should not be expected to

flatter. Of course, there is no reason why it cannot. Many great ones do. It’s just not the general

intent, not a prerequisite. However, it’s reasonable to say that a portrait should never be

deliberately insulting. The parties on opposite ends of a lens, let alone critics, don’t always agree on what is good or bad. For instance, some photographers may have no compunctions about

showing every whisker and pore on a man’s face. But would we dare show such sharp detail on a

woman’s face? It depends. There will certainly be exceptions. What about retouching in post-

production? What about makeup? Even men need a little help sometimes. It may be a practical

consideration for, say, a magazine cover if not for art’s sake. There are no rules governing

personal photographic style and technique.

Portraitists, whether they rely on film, pixels, pencils, or paint, are storytellers. Those

who use a camera are concise storytellers indeed because they work in a medium with only two

dimensions (unlike sculptors) and only one frame (unlike moviemakers). Portrait photographers

have less leeway for explication than writers (in particular biographers), who can exploit their

readers’ boundless imaginings. One also hopes to make a portrait during an important episode in

the subject’s personal life or career because it adds to a good story, and the moment itself is

preserved in a historical context.

A compulsion to create art defines humanity. Seeing humans as the subjects of art comes

full circle with portraiture. When photons bounce off living beings and pass through an aperture of glass, propelled further through the barrel of this lens by an occult force called “the

mind’s eye” to converge at a focal point on a light-sensitive substrate inside a dark box, two

parties on either side of this contraption, a camera, are committed to telling a short story for one

endlessly enduring moment. That’s portraiture, the still life of a human being. It’s magic.

Gerald McKeegan, Chabot Telescope © Tom Zimberoff