Regrettably, there seems to be a widely-held notion these days that photography is no big deal.

After all, everybody’s got a camera.

A generation has come of age with the internet and the iPhone that sees photography as a

seamless and effortless pursuit, just another quotidian activity automated by technology to

subordinate human decision-making. Maybe we can exclude pro photographers from that

reflection, but legions of people compulsively take picture after picture, hoarding them in

profusion, never to be looked at again after their first appearance on a tiny screen.

As a society we once cherished the “Kodak Moment,” a marketing masterstroke, now

quaint since falling victim to — I’ll coin a new word —

photobesity, a mind-boggling deluge of

desultory snapshots created with such careless frequency that they’ve devolved into yottabytes of

digital dross. Visually-preserved memories, once precious, carefully curated and displayed, now

languish in a virtual vault that is less frequently visited than that proverbial shoebox full of

family vacation photos forgotten in a dark closet. It’s now called “the cloud.” And we are

continually nickel-and-dimed by Apple, Google, and Dropbox, alternatively dunning us or

surreptitiously renewing our subscriptions to pay for ever-increasing gigabytes of ephemeral

storage space for our abandoned pictures. Forget about the environmental costs of maintaining

such a billowing cloud, this phenomenon comes at the expense of our eidetic memories, the

deeply embedded kind that we hold dear, that linger in our mind’s eye and would otherwise

resurface vividly throughout our lives, allowing us to emotionally relive meaningful experiences.

But photobesity doesn’t help us remember; it leads to forgetfulness by trivializing events.

The

camera captured it, so I don’t have to. Photobesity denies our neurons a chance to coalesce

around what we witness.

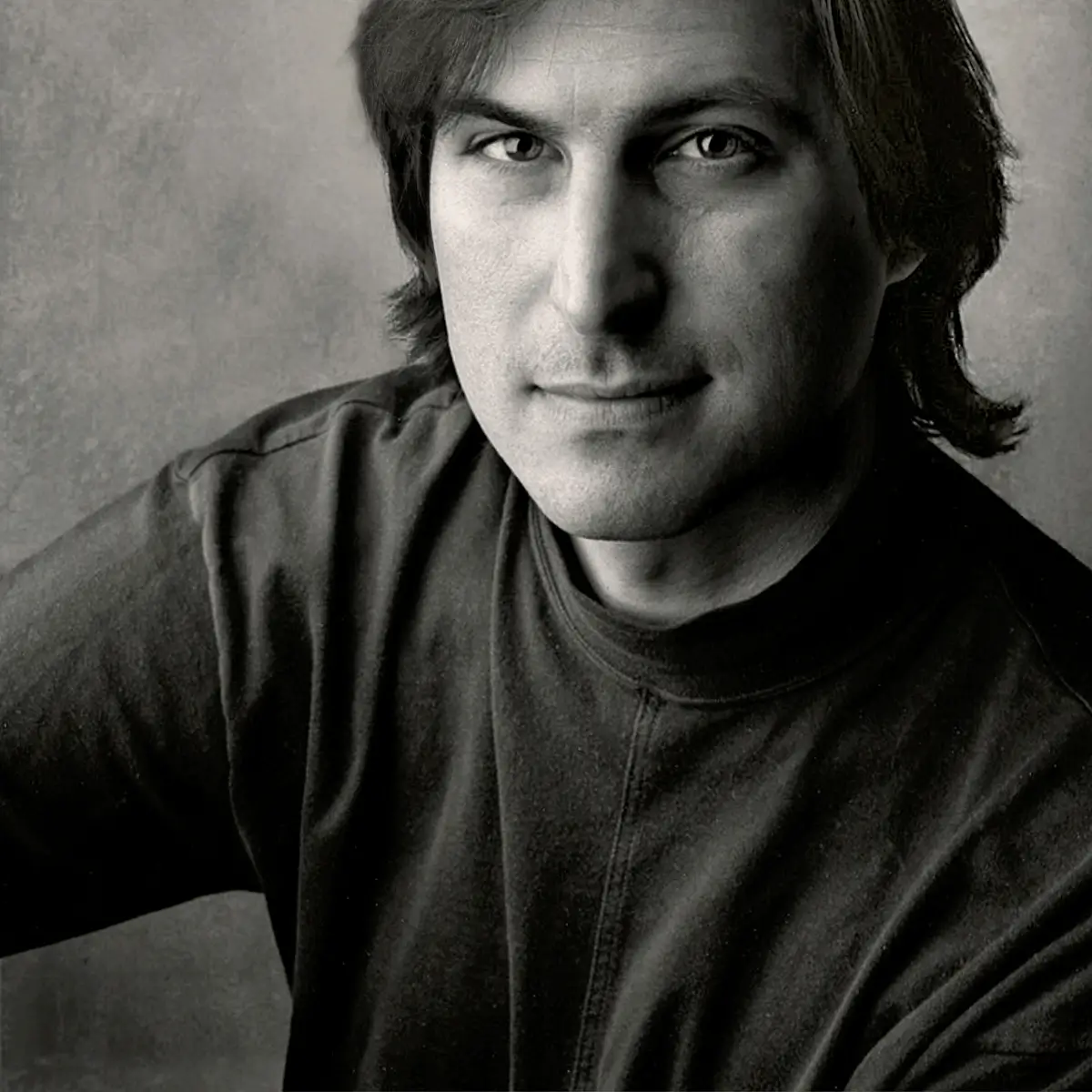

Great Hwy © Tom Zimberoff

Great Hwy © Tom Zimberoff

I seem to have made an argument against digital photography. But that’s not my intention

at all. Let it lay the groundwork for a more substantive observation. (Okay, maybe a gripe.)

Photography’s more sophisticated practitioners, particularly artists, can hardly afford their work

to be perceived as effortless and consequently taken for granted. Their anxiety has led to a

regressively perverse phenomenon: A like-minded school of photographers seeking to elevate

their artistic credibility has eschewed digital image capture altogether and, instead, embraced the

use of obsolete cameras, from handheld 35mm SLRs to monster view cameras, so they can use

film exclusively.

Based entirely on my imaginary credentials in psychology, I’d say that their rationale for

going retro is simply because it’s harder. Exposing and processing film, from sprocketed rolls to

sheets the size of an iPad, then enlarging prints in a darkroom with all of the other paraphernalia

and secret sauces that that rigmarole entails, may also assuage a sense of guilt by giving some of

these photographers a greater sense of accomplishment.

If it’s too easy, anyone could do it. Or

maybe they want their audiences to believe that — a public relations ploy. That may be too cynical because it’s possible their movement is merely grounded in nostalgia and curiosity. I’ll

also renounce any glib but risible notions about the influence of independent wealth and a

corresponding disregard for the exorbitant costs associated with film, given that

digital is

virtually free (after an initial investment in hardware and software). But one of the fallacies this

new school espouses is that, by using film (which is ten times more expensive than it was pre-digital days), they are more discerning about when to press the shutter than the rest of us sloppy

digital shooters who machine-gun dozens and dozens of pictures, hoping to get one good shot out

of the whole bunch. They may also believe that digital shooters will indolently rely on algorithms as a crutch to make up for poorly-exposed pictures. But in making such an argument, they rarely consider how darkroom techniques were, and still are, used to correct for difficult exposure circumstances (and mistakes) by “pushing” and “pulling” chemical-development times for film, dodging and burning prints, and using variable-contrast photo papers. And let’s not leave out the tried-and-true technique of “sandwiching” (or masking) either slides or negatives and then rephotographing them on a repro stand to create the analog equivalent of HDR (high dynamic range) photographs. We did that, too, back in the day.

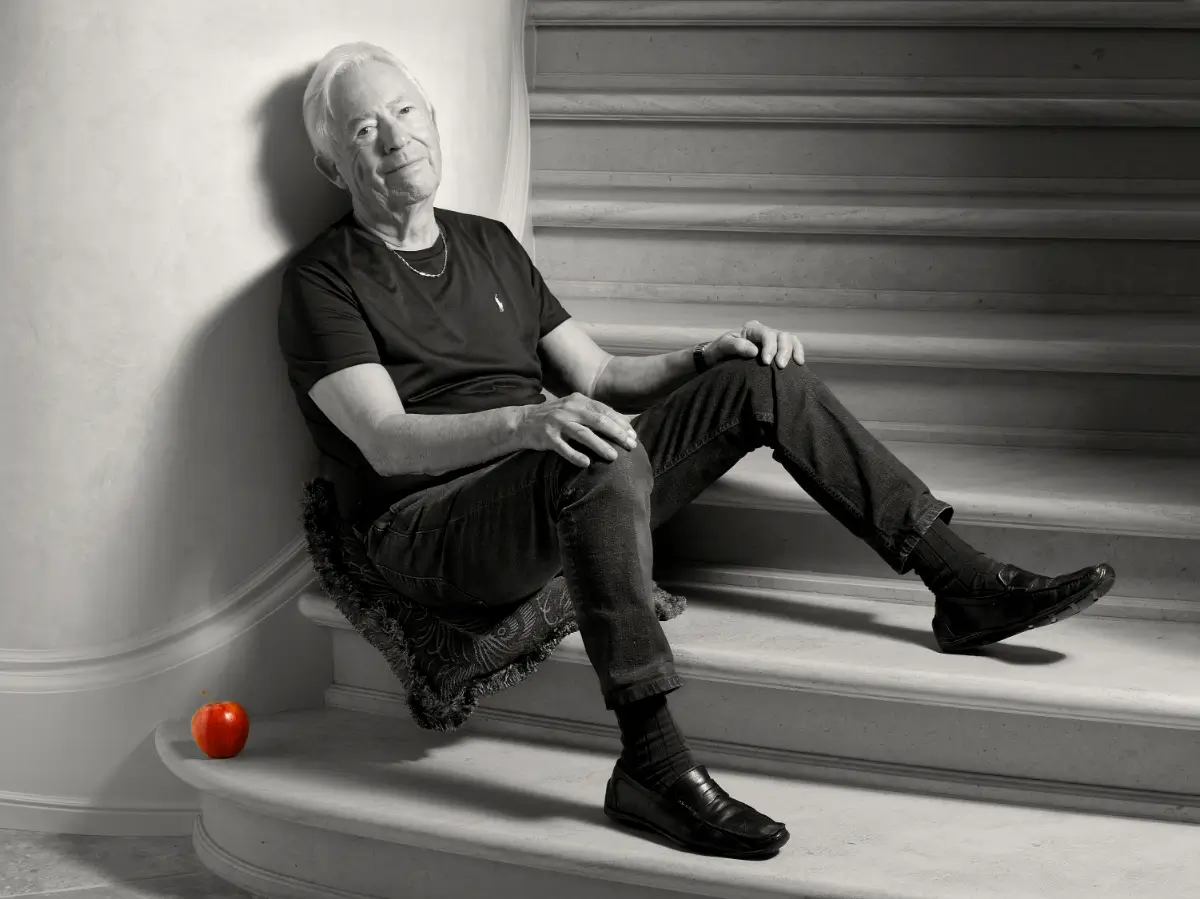

Photographing Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak in 2024 © Tom Zimberoff

Steve Wozniak, 2024 © Tom Zimberoff

There is an implicit if subconscious claim in such beliefs that analog practitioners are inherently superior to their digital colleagues.

I once had a television network client whose assignment editor admonished his minions,

including me, “Film is cheap; shoot by the pound!” It was the fastest and cheapest way to create

color “dupes” (i.e., copy 35mm slides) for distribution to, and publication by, affiliate TV

stations and advertising outlets across the country. An unyielding shutter finger and a Nikon

motor-drive did the trick. But with that singular exception, never to be repeated, all serious

photographers remain as conservative now as we were then about how many frames we shoot to get the right one. (Me too, despite having since “gone digital.”) Nobody wants to spend

interminable hours separating the wheat from the chaff in post-production — what we used to

call editing. Besides, all pros, whether practicing in the realm of art or commerce, still do the

hard stuff like manually adjusting f-stops and shutter speeds, whether we use digital or analog

cameras. That’s enough to separate us from the hoi polloi if it makes us feel better to do so.

Incidentally, photographers have embraced auto-focus since the 1980s.

Consider Kodak’s ubiquitous Brownie camera (1900–1967 — the iPhone of its day, albeit

incapable of talking and texting) and its original slogan:

You Press the Button, We Do the Rest.

Today, aside from keeping my fingernails from turning brown, immersed in sloshing trays of

selenium toner and Dektol, instant gratification on an LCD screen is the only thing that’s new —

the erstwhile original Polaroid notwithstanding.

It used to be that no one had a choice about shooting film, only about which kind to use

for which application. I enjoyed processing it and making prints in my darkroom. I fondly

remember the smell of gelatin film; but not so fondly the smells of potassium ferricyanide and

sodium thiosulfate. Today, however, when film is added back into the mix, resuscitated after its

last agonal gasp, the arcana of working in the dark with noxious and environmentally unfriendly

fumes, while it may be novel and entertaining to some, represents a regressive response to the

criticism that photography is too easy:

My kid could do that! Who are you, with your 11x14

Deardorff, to tell me I can’t do the same thing with my iPhone? Laypeople have always railed

like that. That’s why they’re laypeople.

The school of artists that prefers film will also argue that they can see subtle differences

that justify all their fuss. This is silly to me. Been there. Done that. Got the T-shirt. The end

results are essentially the same. I dare anyone to eyeball any difference between a photograph

I’ve captured and printed digitally with one of my earlier, film-captured, silver-gelatin prints.

That might not have been true ten years ago, but it is now. Not even large-format sheet film can

render qualitative superiority anymore.

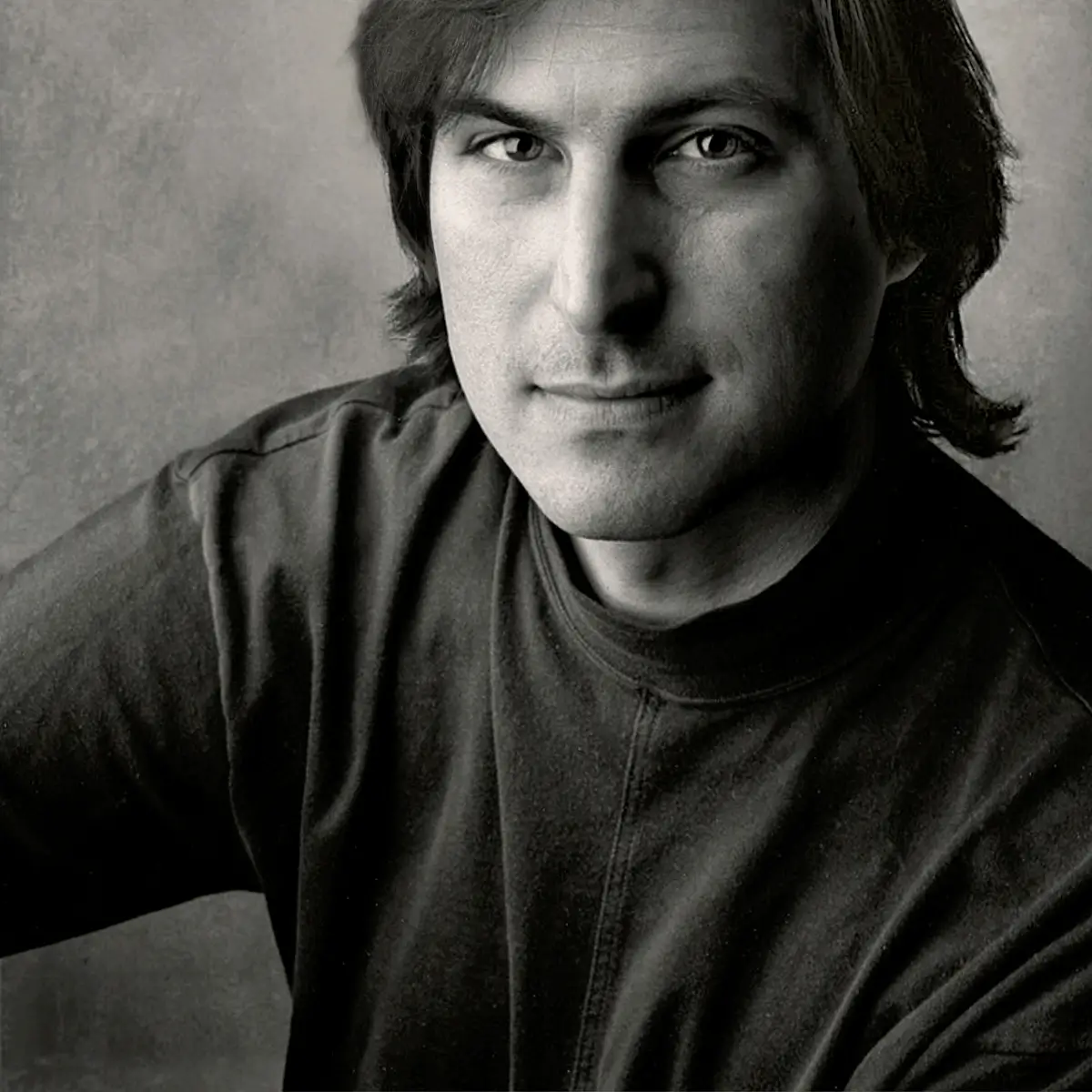

Steve Jobs ©1987 Tom Zimberoff

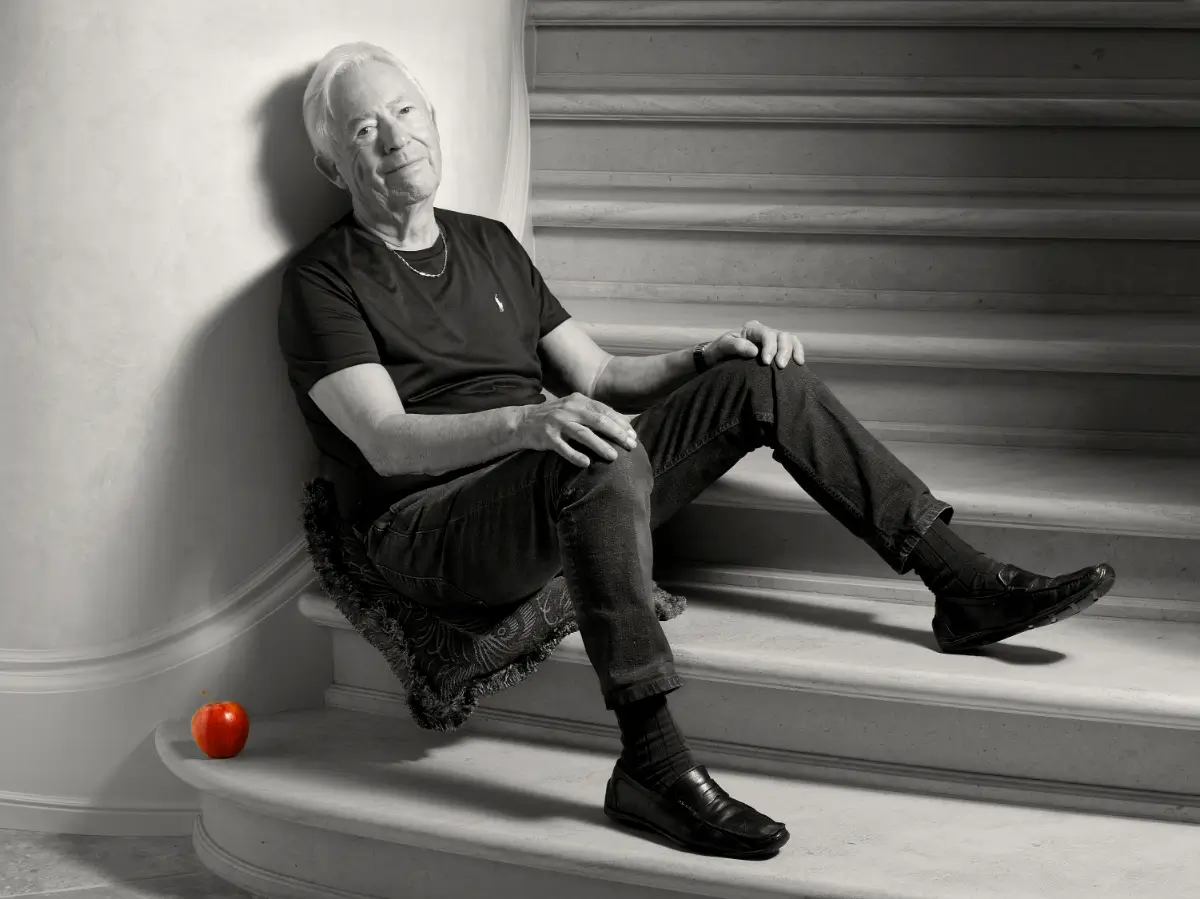

Mike Markkula ©2023 Tom Zimberoff

I will say this, however, in favor of film for capturing images, despite exhibiting no

superiority as a steppingstone to view them (as physical prints). Once processed, film is the more

practical medium for archival preservation. Its physical properties allow it to be more easily

preserved for posterity than jpeg, RAW, tiff, and DNG files stored in that fugacious shoebox in

the sky or even on a personal hard drive array. Then again, I won’t be around six hundred years

from now to care. But much sooner than that, if a not-too-farfetched and foreboding sunspot

flares up and fries Amazon’s Web Servers, or the Russians reduce Google to gobbledygook with

a malware attack, you’re shit out of luck. Or what if you haven’t had the discipline to back up

your photos on a regular-enough basis to keep up with the tick-tock of technology, let alone the

physics of entropy, and your CD-ROMs have succumbed to “disc rot.” (Do I need to burst your

bubble by citing oxidation of the shiny reflective layer and a breakdown of the polycarbonate

substrate, delaminating the whole schmear?) Or what if there’s no computer, say thirty years

from now, that can still “read” those

ones and

zeros that you assiduously backed up. (What

happened to the video Betamax and your CD-ROM player, anyway?) Yeah, shit out of luck

again. Generally speaking, I used to put my film in an envelope and stick it in a drawer, relying

on the likelihood that my photographs will be seen by my descendants living on Mars

(notwithstanding fires and floods on Earth in the meantime). If you want to ensure that your

digital images last long enough to be read by Jean-Luc Picard, I suggest you make prints of every

one of them. But back to the argument in favor of

digital, a pigment print made on rag paper with

an inkjet printer will last as long as any chemically-processed silver print. (That goes for both

color and black-and-white).

For those who evangelize film, their message is clear: By deliberately avoiding digital

technology and favoring inscrutable darkroom alchemy instead, nearly moribund though it is

economically, and insisting that the medium (of film) is the (better) message, they are bestowing

themselves with an aura of exclusivity and special powers that supposedly produce superior

results, whether by divine favor or the favor of similarly sorcerous academics, critics, curators,

and gallerists. Their anachronistic zeal for antediluvian technology reminds my cynical side how

ancient priests shrouded their religious rites in mystery and complexity to awe an uninitiated

populace and reinforce their own elevated status.

Taking photographs is and always has been easy. Making them is not, nor has it ever

been. Bottom line: My story, then as it is now, and the stories of all working artists and

photojournalists, whether we prefer digital or analog tools in our camera bags, is that we do

indeed

make photographs. Let the dilettantes continue to take them.