[Our face is our billboard, yet, it's a subtle cryptic display of our psyche, and our body is the location of its myriad conditions. Our face is

always a facade, a curtain of sorts that hides our vulnerabilities, and our manifold motivations that the body tries to reveal in its many

contortions, gestures, shifting, flexing and nuanced dynamics. Our primary objective as a photographer, is to unravel this billboard, to bring

that paradox of the psyche and the body together in our subject, to undress our subject, make them comfortable in their skin to reveal their

humanity. A rare few can achieve this, in their magical ability for metamorphosis, in becoming that invisible combination of Psychotherapist-

hypnotist. I knew one such twentieth century master, Art Shay. He was our invisible photographer.]

“A great portrait artist has to be a great bullshit artist...” – Verrocchio's Workshop, Florence. Overheard during the Renaissance

Portraiture is mimetic likeness in any medium that has its roots in three psychological components, vanity, sentimental-memory and immortality.

Vanity through immortality or vice-versa is perhaps the oldest symbiotic concept for reproducing likeness, the last being sentimental, which is about loss

and remembrance. The oldest known portrait is from about 15,000 BC, and the oldest recognizable likeness comes from Egypt. We can readily recognize

Tutankhamun, Rameses, Akhenaten, Nefertiti and many others on the monuments there, because of consistency in depiction. This symbiosis went

through several evolutionary shifts, from petroglyphs and lithoglyphs in prehistory to stone carvings and paintings of the earliest civilizations through to

contemporary times, which still continue as commissions. The portrait-busts of Roman emperors are examples of three dimensional likeness still being

produced, long after the empire had expired. However, aesthetic presence has no expiry, like Michelangelo's David or Moses.

The advent of painting coincided with carving-sculpting early during the Egyptian civilization, followed by the Greeks, then Romans. The first two-

dimensional likeness on a flat surface in natural pigments was with the ancients, and much later in oils. The first iterations of the now ubiquitous selfie

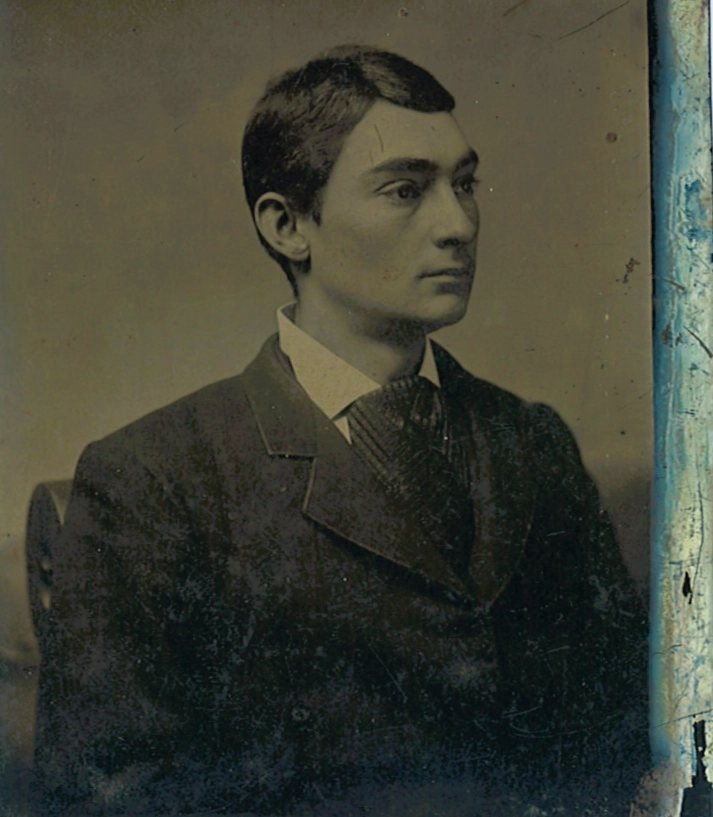

was by the likes of Da Vinci, Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Picasso and others later. In the 1830s, photography's birth was an alchemic paradigm shift that

transformed portraiture from being something of an impression or representation to an exactitude and literality, as in the many Daguerreotypes,

Ambrotypes and Tintypes that are still extant. Today, over ninety million selfies (self portraits) are taken daily with smart phones. It's a macrocosm in the

art of vanity in self preservation. This small exploration is about the psychological context in portraiture, not on techniques that's available in a plethora

of publications.

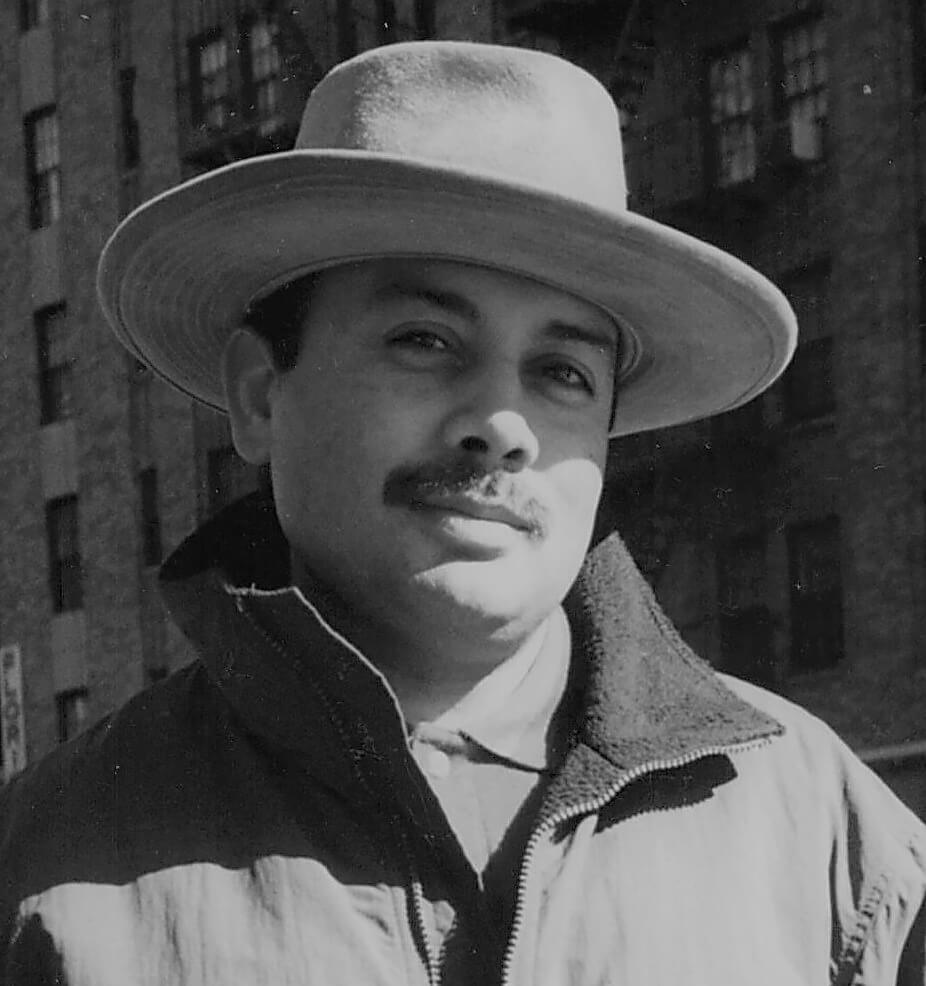

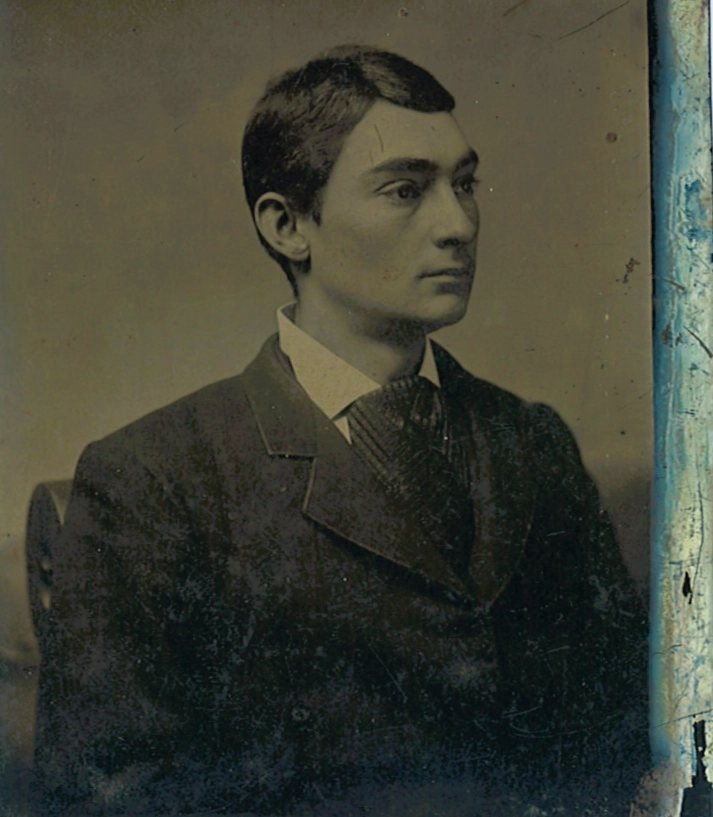

Rare, early 19th century portraits from Peddada Collection: Ambrotype 1875

Rare, early 19th century portraits from Peddada Collection: Daguerreotypes 1856-1858

Leonardo Da Vinci's 'Mona Lisa' is, arguably, the greatest portrait for many reasons. Mona Lisa's notoriety is not because of how

beautiful it is or what it reveals, it's precisely the opposite, for what it obfuscates, and how perplexing it is. Italian architect, historian and biographer,

Giorgio Vasari had speculated that this was indeed Da Vinci's objective: to paint a countenance that in itself induced queries – I might add, right into the

21st century. What James Joyce had done to literary fiction at the beginning of the 20th century, is what Da Vinci had done hundreds of years ago to the art

of portraiture: to not reveal, but, to compact it as subtext, to baffle, by concealing to symbolize, by densely packing our various conditions into a day in

the life of – or in a face. As works of art they shatter every molecule of convention, as pressurized mystery devices that tease and release only to

concentrated acuity and sustained inquiry.

The masters of form and composition; and the maestros of disarming. Michelangelo, Raphael, Caravaggio, Jacques-David and others were the prior,

but the latter are another breed, like Vermeer, Rembrandt, Da Vinci and Hans Holbein. The prior worked on large scale compositions from reference in

solitude, the latter worked while interacting with their subjects. One in particular is worth our investigation, which is Hans Holbein. He was invited to

England in the early 16th century by the then revered Dutch humanist, Erasmus of Rotterdam, which coincided happily with Holbein's search for work.

Soon enough, and with a letter of introduction from him, he found his first subject in a brooding, reticent, pious and reflective Thomas More – someone

incredibly tricky and intimidating, a moral intellectual of that age. But before I flip the muslin off of Holbein, I must probe this art form some more.

Portraiture is hardly about the subject in a literal sense, but more on potential, what they seem to be, or their transformation from one state to another. The

subtext of all portraiture is the contention between the artist's style and metier versus the subject's changing moods. Just imagine what Holbein puts up

with from an amused Cromwell enjoying the artist's company, changes to a villain upon some unfavorable news. Which countenance is more gripping for

the painter and for that matter, audience? And, will the subject allow such likeness? The contemporary equivalent are the emotionally charged lugubrious

portraits of Marilyn Monroe by Richard Avedon. I wonder, if she had come in a happy state only to change dramatically on location. And, why did she

allow herself to be photographed in such a state, or was Avedon just too quick? Well, you see, Holbein couldn't effect a quick shutter release to capture

Cromwell's sinister bearing, therefore what he got was a carefully composed posture. Photography has dramatically affected portraiture. Portraiture as a

narrative on and of the subject is now dialectical proposition between the prior and the latter medium.

Sir Thomas More, 1527 © Hans Holbein, the Younger, Frick Collection, New York

Now think about this. If one is a portrait painter, regardless of the era, one had to be a cogent conversationalist, someone with enough

intellect or intelligent humor who could manage to keep their subject engaged for hours on end, while they sketched them out. A portrait could take

weeks, an hour here, two hours there, and maybe three hours on a rainy day, when outside distractions were minimized. In all of this time, the artist

invited conversation from his subject: first, to keep her there, second, to extract by leading them into various subjects to fish for their humanity, that

people, especially of stature, keep their vulnerabilities behind their trained implacability and inscrutability – like Thomas More. A portrait artist has but

one objective, which is, to turn the subject into subject's own mission: which is, to come off looking good, and to exploit artist skills to make herself or

himself look true to themselves. This was a symbiotic venture where failure as well as success was interdependent and intrinsic to each other. To do this

was complex – required more than just canvas, colors and brushes. It had required something else.

For Holbein's sake, he was fantastic company, he had disarmed More with his jest in travels. He, in fact, was so good, that he hobnobbed with most of the

aristocratic courtiers at the Court of Henry the VIII. He soon got himself the wiliest subject of all, Thomas Cromwell – a man, who even Thomas More

was weary of, and simply the most feared man in all of England and possibly the continent, in the mid 16th century. Many had claimed that you never saw

him coming at you, and you sure as hell never knew he was there at all. The Holbein no one knows is that street smart humanist who had opened up the

man who everyone thought was a fortress. He was a supreme psychologist. He had used counter-intuitive psychology on his subjects – pushed them

negatively to see if they reacted positively, or pushed them positively to get negative responses. The interactions lasted for days, as they became friends.

Besides Holbein's personal journals revealed his subject more precisely – “...he revealed nothing, but had everything on me...” Cromwell, who was

terribly hard to impress, was astonished at how Holbein had rendered him bare. This minister of Henry, then gave his artist the biggest subject to contend

with, literally and figuratively.

Henry the VIII was a capricious monster, an irascible giant, the colossus of English history. I cannot imagine Holbein's reaction and his first words to a

man who was irritable, physically feared, replete with infirmities, by the time he had arrived at the court. Henry had once addressed Cromwell, “my only

friend...” then days later, direct to his face, “you are a serpent, sir...” Holbein, it's been noted, once had seen Henry stand with legs apart, hands on the

hips, as if ready for a battle, chewing out a courtier – it's this image of Henry that was immortalized by Holbein, in his massive portrait – he then

proceeded to paint the entire royal family. In the span of a few years, he had painted at least five seminal figures of English history for posterity. This is

well beyond the art of portraiture. What was it about him that gave him access to complex people?

With Thomas More, he had to contend with moral philosophy and religion, and with Cromwell, it was banking and trade, arbitration, statecraft, thuggery

and intrigue. But what could he discuss with the king – anything little thing could ruffle his mane, it was like walking around the proverbial slumbering

lion. With a young Elizabeth, the brooding queen Katherine of Aragon beset with infirmities and her spastic daughter Mary what topics would be broach?

These are hardly simple folk like Monroe in front of (Richard) Avedon or a Hemingway posing for (Yousuf) Karsh. These were people who lived in an

unstable realm, fearful and on the edge, and bristled at mundane demands, yet they were spoiled and entitled in many ways. Holbein had to engage such

prickly combustible folks, not just for a shutter release, but for weeks on end. So what was his methodology? In the least, he had to be very observant,

like a trainer of a lion, watching for its body language; have a sharp sense of humor and wit, a sense of irony that was fast in tune with the subject's

condition and didn't trespass; and most importantly, empathy. Not sympathy, but empathy, capacity to see things from their POV, be in their shoes.

Empathy is an underrated tool in modern portraiture, which is overly focused on the externals, not within. Holbein's biggest tool was empathy.

Centuries later, so it was for Margaret Bourke-White who photographed men of polar characters with equal ease, Gandhi and Stalin. Dorothea Lange was

another who became an insider with the dust bowl migrants or Steve McCurry's piercing Afghan Girl for NG that encapsulated the whole condition of a

region in her eyes. The real tragedies in photography are the contemporary fashion shoots, where algorithmic androgynous models all appear to be

manufactured by a machine of banality and vapidity, shot in gratuitously exotic locales, and sporting that cookie-cutter ultra-feminine pouting-smoldering

looks with flat tall physiques that render them like cutouts by some jaded teenager doing homework, and in couture that contradicts the mood or

atmosphere. This unfortunately reveals a very narrow focus on non-contextual themes and externals – with no psychological component at play, least of

all empathy. All we have to do is pick up four-five fashion magazines and audit their fashion pages to see what ails contemporary fashion photography.

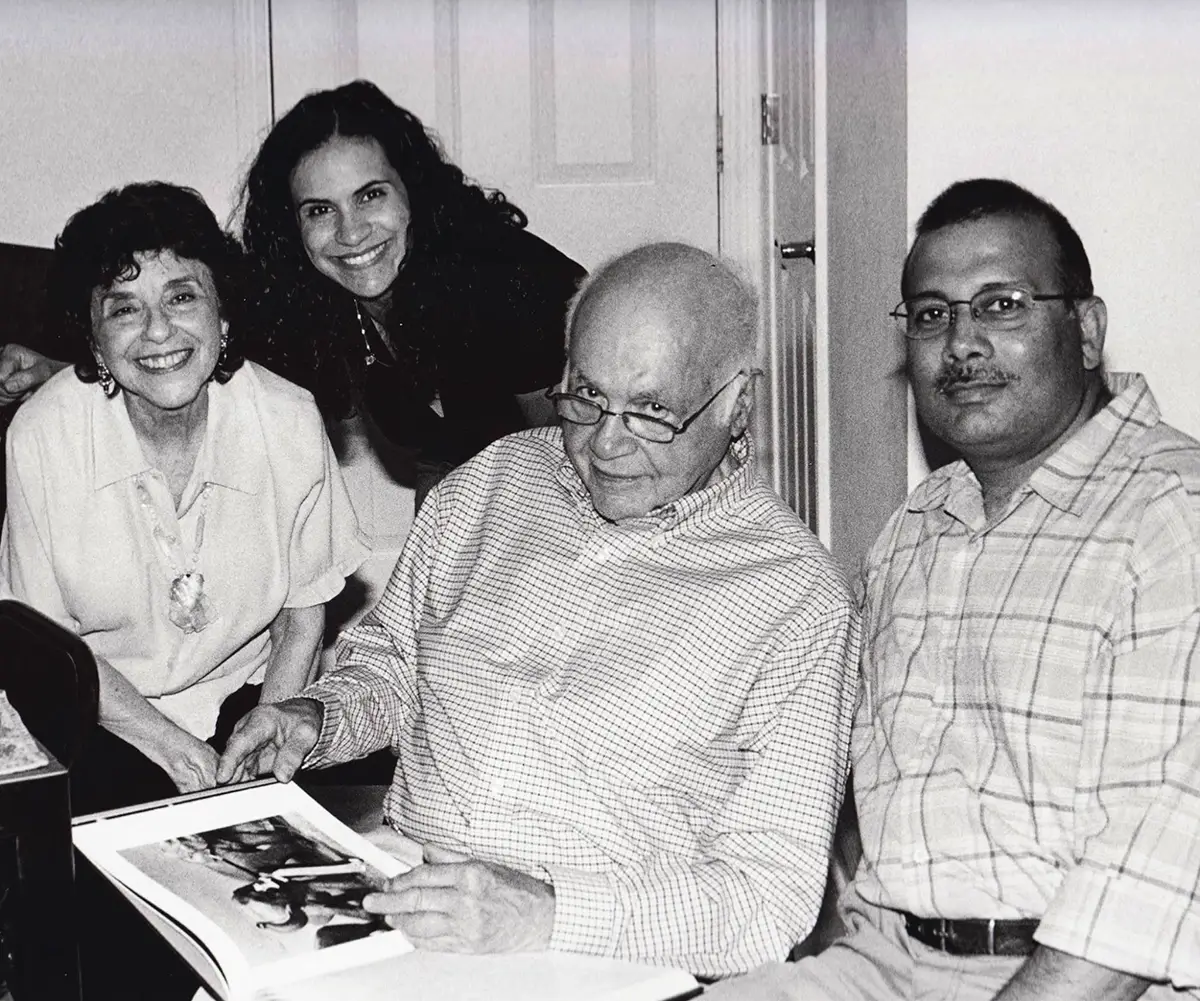

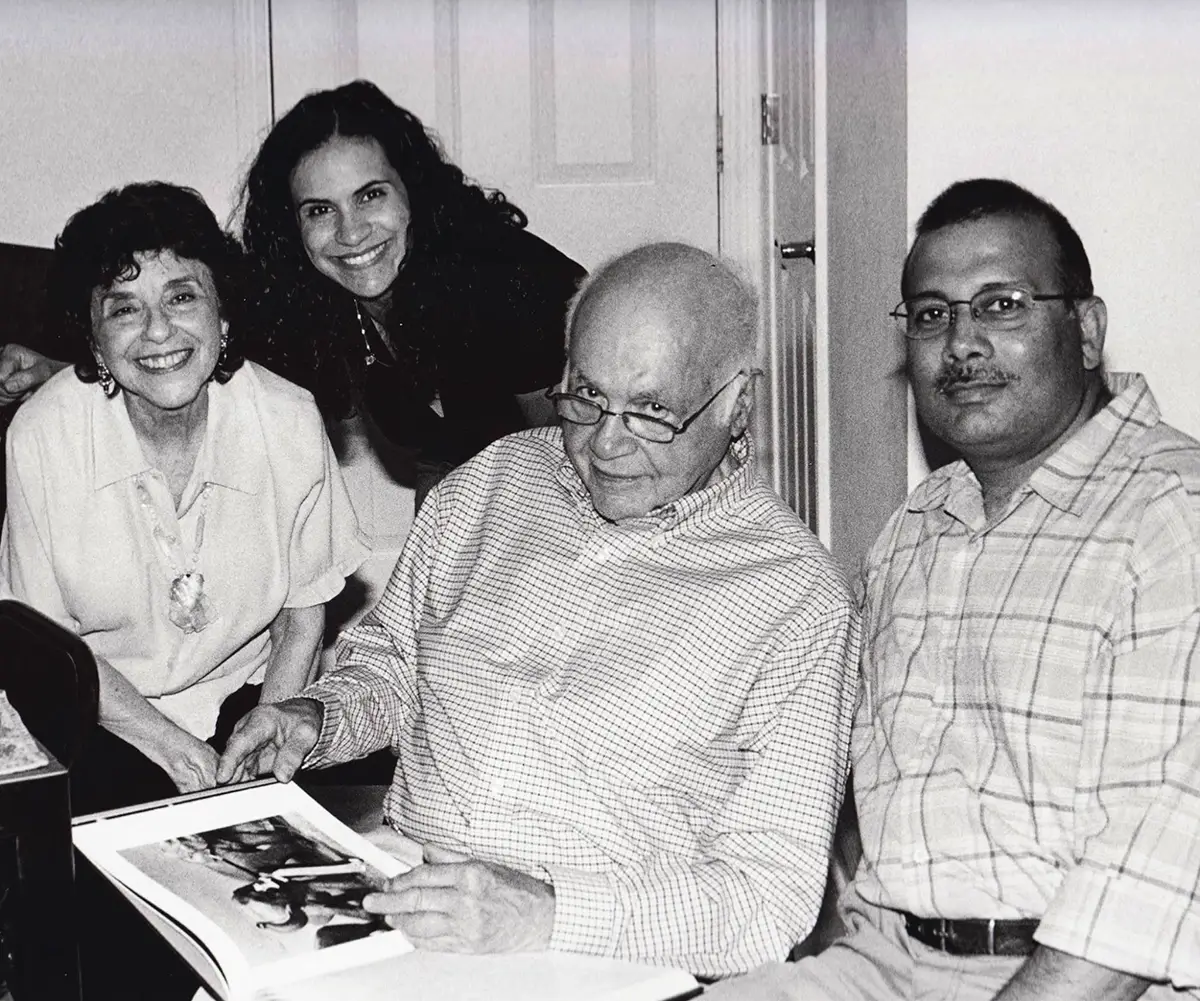

Art Shay, Florence & us at our party © Raju Peddada

At my summer party years ago, Shay and his wife, Florence, were in attendance, so were some of my other friends, his fans,

editors from Chicago Tribune, Chicago magazine and the Reader. Let me tell you, it was really a workshop to behold. While everyone reacted

humorously over a bawdy jest, he, Shay, casually took my camera with its flash attachment off the table, as if checking it out, rather unobtrusively,

inconspicuously, fiddling with it by removing the flash attachment. Our toddler boys, withdrawing from group laughter that sounded like several

discordantly loud toucans, came and joined us as we sat on the floor looking up and sharing the same with Florence, sitting slightly to the side of her

husband, while he, Shay, appeared occupied with my camera. I thought nothing of it and nothing ever occurred to me, even after I saw my lens settings

tampered, from F5.6/125 to F2.8/60. Three weeks later I found out.

We were thumbing through a monograph on the 100 greatest photographs, and were debating on the best. One briefly commented on by Shay was Robert

Capa's searing picture of a soldier shot-falling-dying during the Spanish Civil War. The party went on – inebriated, one by one, everyone present upped

the ante by sharing their worst experiences. Shay, initially resistant to the whole idea, relented, and shared an anecdote, like Tolstoy would, in a very

understated manner in excruciating detail, as if some distant fishing trip gone awry.

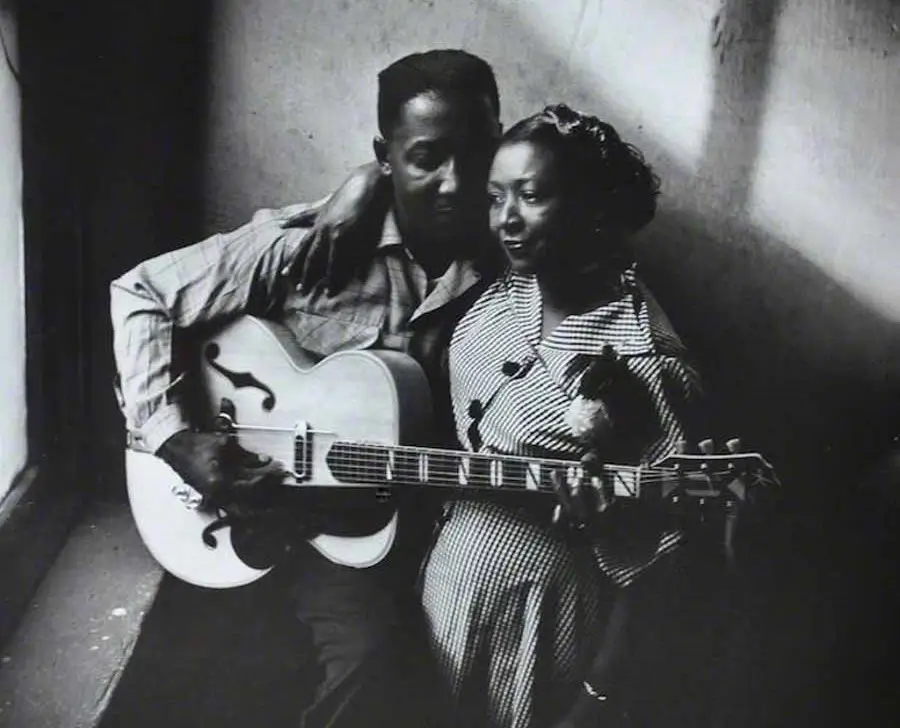

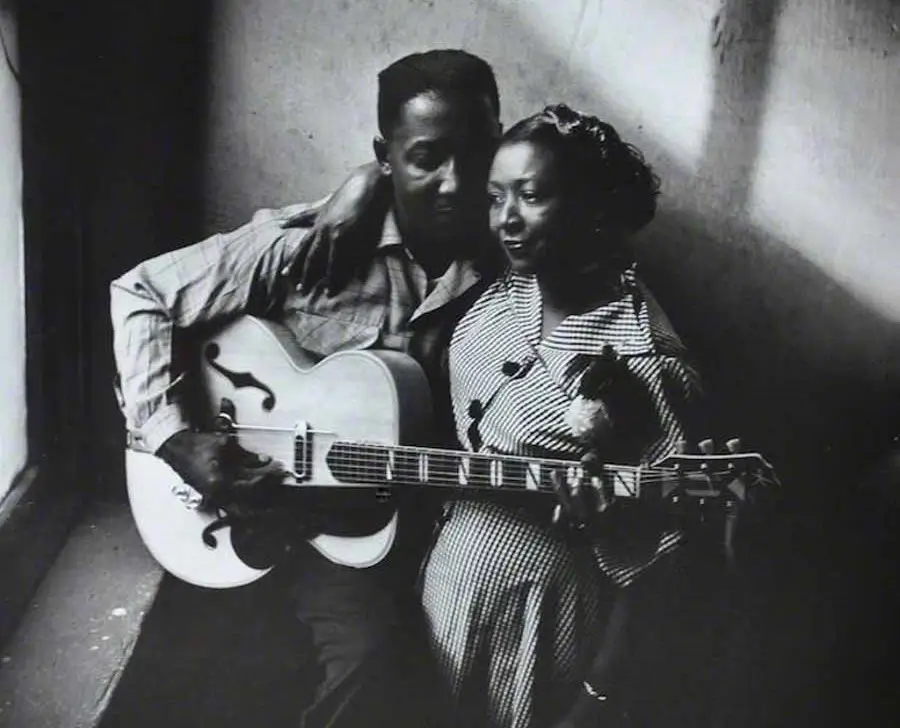

Muddy Waters & Friend ©Art Shay

His anecdote was on a return trip from England to the U.S. – their B-17 had crash-landed on Greenland as their gas ran out – supplies scattered as doors

came open on a hard landing on hard glacial ice as it scraped to a stop by the edge of an abyssal crevasse. Shay, alive and rattled, with mental faculties

intact – had followed a brown trail for about fifty yards behind the plane on ice, and there he found the plane's toilet perfectly upright, only that the seat

was vertical as if for the takeoff. He being the inveterate and incorrigible punster, took a picture of the plane through the seat, completing his

metaphorical masterpiece. The whole anecdote was a case of intense drama that began with a catastrophe which was rescued by laughter. We all sat there

agog in silence for a few seconds, before we broke in laughter and clapping – but, Shay had me on another opportunity to experience the same. On the

contact sheet, three weeks hence, I saw about 5-7 perfect family portraits in glorious B&W of us and our boys on our laps. I was astonished, and couldn't

help but become emotional over a classic family portrait by this maestro, the LUCIE Prize winner. I had experienced the invisible photographer.

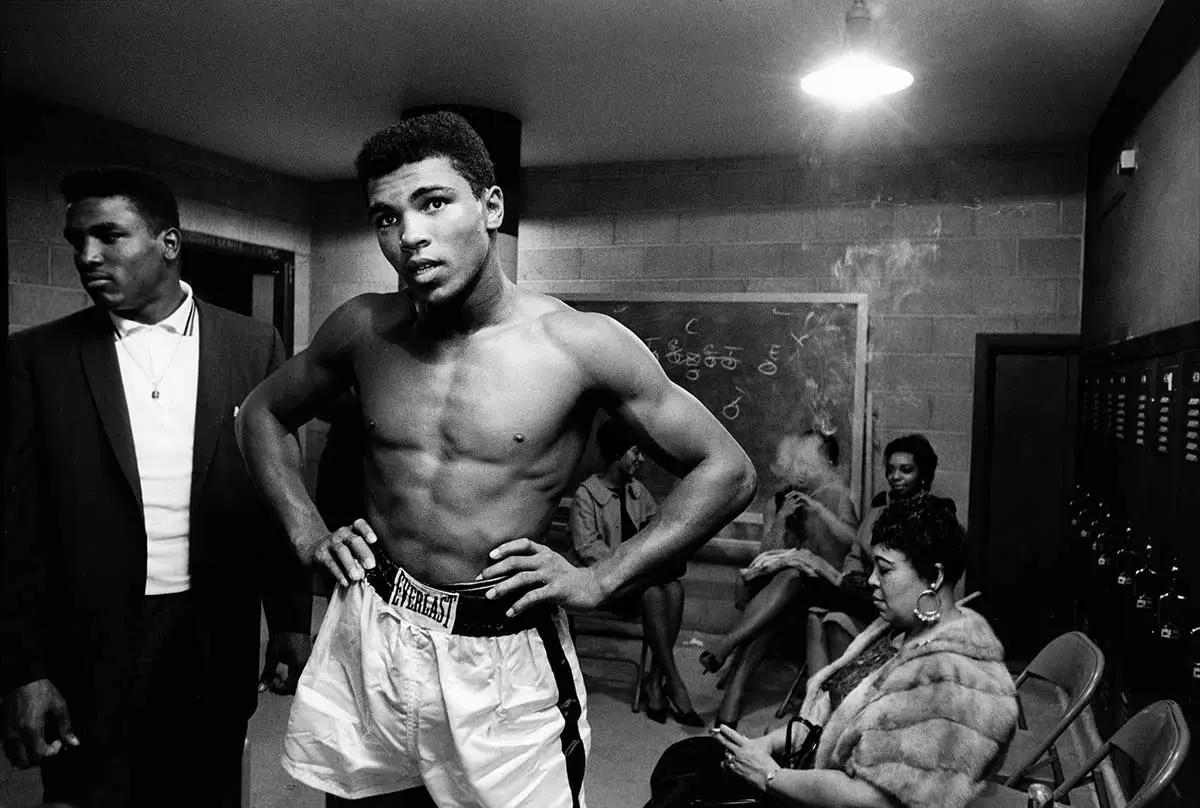

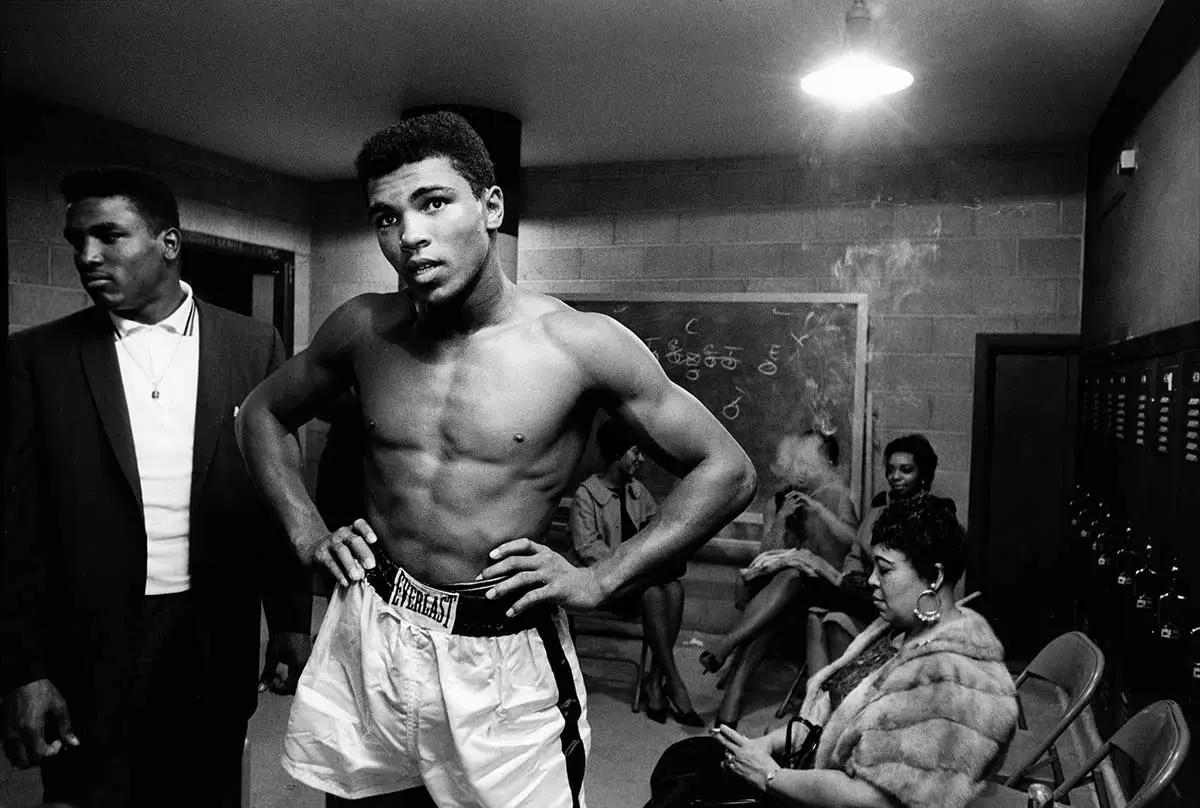

Cassius Clay by © Art Shay

I was given the privilege of using some iconic images for this article by Mr. Victor Armendariz, at Gallery Victor, Art Shay Photographic Estate's

worldwide representative, from his vast archive: Muddy Waters and fiance, Johnny Cash, and Cassius Clay still as the chrysalis of a fighting machine

well before becoming Ali. Of course it's no accident that in each photograph there's no inkling of Shay's presence. That shadowy yet moving image of

Muddy Waters and his lady were by a natural source of light. They seemed oblivious of anyone around them in their deep attachment. Clay's shot was

almost as if the pugilist was doing his bidding in front of a large mirror – it well might have been, because Shay himself, in many ways, was like the

boxer, a veteran of many a fracas, and he knew how to exact or extract reactions. It simply demonstrates that portraiture is not about the subject waiting

for the set up, rather, it's about the photographer being organically ready for the subject. The subject must never be aware of anything as being a subject –

which then enables natural dynamics to unfold, as revelations thru any physiology are rapid and fleeting. In such situations, a good photographer is

essentially a compound eyed dragon fly – hovering over possibilities – that small flexing, twitching or move that revealed any food for thought – to be

snapped up.

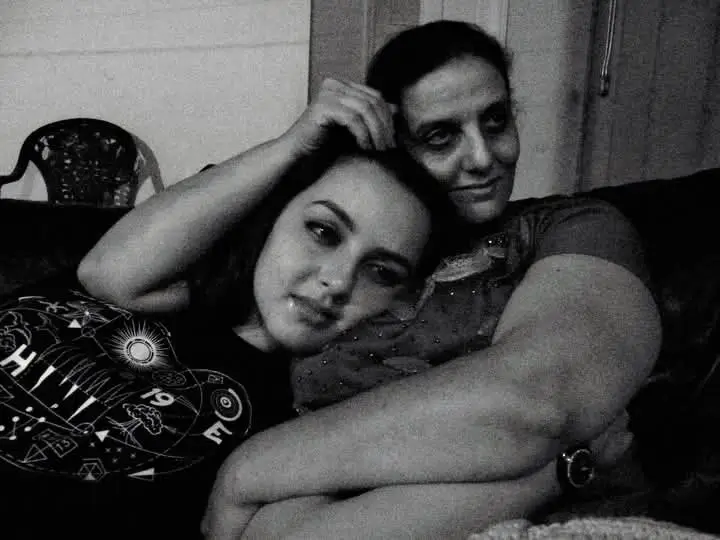

There are no set strategies or rules to loosen up your subjects, except for using your particular or specific strengths to develop instantaneous rapport by

tuning in to their hobbies, interests or inclinations. You just can't ask your subject to pose without any context. I tried photographing a highly reluctant

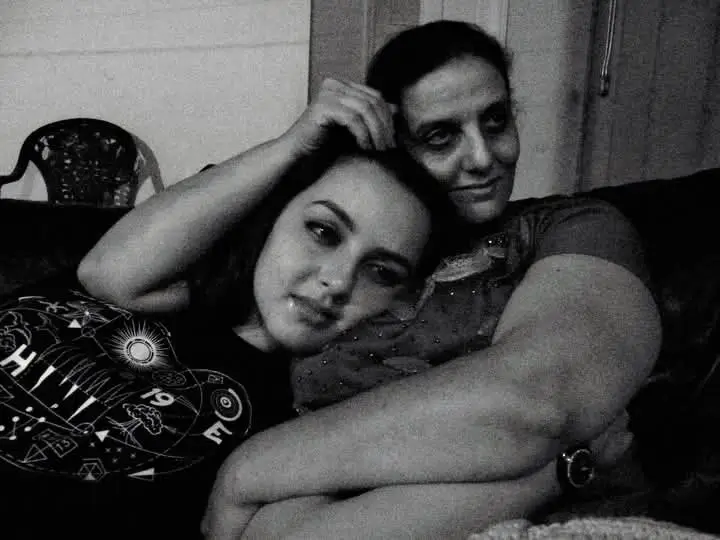

Moroccan beauty, under a rigid cultural protocol who had never been subject to being photographed. I had to find the key – which was her mother.

Subjects responded, in almost every case, contextually. I had found the daughter lived in Morocco, and the mother in the U.S. And when I had asked if

there was any affection between them due to their separate lifestyles – the girl instantly fell into her mother's arms, and I was ready. Then there was my

mother, who was experiencing loss as her grandsons, who were always with her as toddlers, now teenagers, ignored her – I captured her in her poignant

resignation. Through my heuristic experiences, I had stumbled onto such insights with regards to people – we must allow enough time to pass, let them

forget you, be patient, join the conversation and never call attention to yourself, like good writer would, just observe and be ready, for them to unfold.

Moroccan Beauty © Raju Peddada

Moroccan Beauty & mother © Raju Peddada

Finally, an old literary maxim comes to mind which applies to photography – which is, that a writer who announces himself in his narrative or scenic

portrayal of someone or something is a case of vanity at display. As in writing, a photographer's invisibility would surely disarm the subject, release it to

spatially evolve organically, become dynamic in a setting, at which point the subject can take over and move forward on it's own spirit and energy – as

Thomas Mann had experienced on his main character, Hans Castorp, in his magnum opus: The Magic Mountain. And, portraiture is indeed a

photographic mountain to scale, mined on the way up by our subject's attitude of obfuscation, that we, delicately as maybe, dare to reveal.

Copyrighted, January 1, 2025 by Raju Peddada. All Rights Reserved on the Text and images.

Mother resigned to loss © Raju Peddada