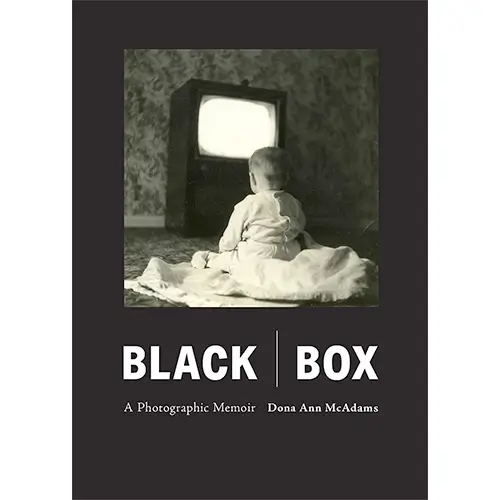

Black Box, a memoir by award-winning American photographer

Dona Ann McAdams, combines fifty years of black and white photography with the photographer’s own short lyric texts she calls “ditties.” The book brings together McAdams’ striking historical images with personal reflections that read like prose-poems. Her photographs, taken between 1974 and 2024, document astonishing moments and people across decades of American life.

We asked her a few questions about the book:

All About Photo: Why is it called Black Box?

Dona Ann McAdams: A black box is a dark room, a theatre, a portfolio box, a camera. A black box holds secrets and history and secret histories. A black box is the thing you consult after a disaster or crash to find out what happened. The name just made sense for me when looking back over decades of work and being surprised by what I found there.

How did you get the idea for a photographic memoir?

After my brother died about a decade ago I started to think about how he was the keeper of our childhood memories. He was the archivist of all things McAdams. At the same time I was organizing my photographic archive in order to find a place for it when I’m gone. As I looked over the span of work, memories of when the photos were taken—or sometimes just memories triggered by them—kept coming up, and I started to write them down. Usually in my darkroom. I had to write them on a pad of white-lined paper with a number 4 soft lead pencil, the same kind of pencil I use to write on the back of my photographs. They came out spontaneously, like little stories, or songs.

After I’d written a bunch of them, I started to share them with others and people responded positively, when I put them aside photographs. Photos that were sometimes related to the story and sometimes not. At some point I realized what these photos and texts were. A kind of visual memoir. Some people called them “flash non-fiction” or “prose poems.” I called them “ditties.”

Empire State Building, NYC 1981 © Dona Ann McAdams

A ditty is a short simple song. I see the text as marking a moment, a kind of celebration. As singing. They’ve always been ditties to me. It’s not that they’re unserious, it’s that they’ve come about as a spontaneous reaction to a feeling or a memory or a mood.

There’s a theme throughout your work involving women and gender. You take a lot of photographs of women looking, women in contemplation. What’s the fascination with women?

I love women but I’ve always been ill at ease with my own gender, my so-called gender assignment. I’ve never been quite comfortable because what was expected of me as a woman, as a girl. I photograph women in order to understand them better, or maybe understand myself, or maybe just because I am one.

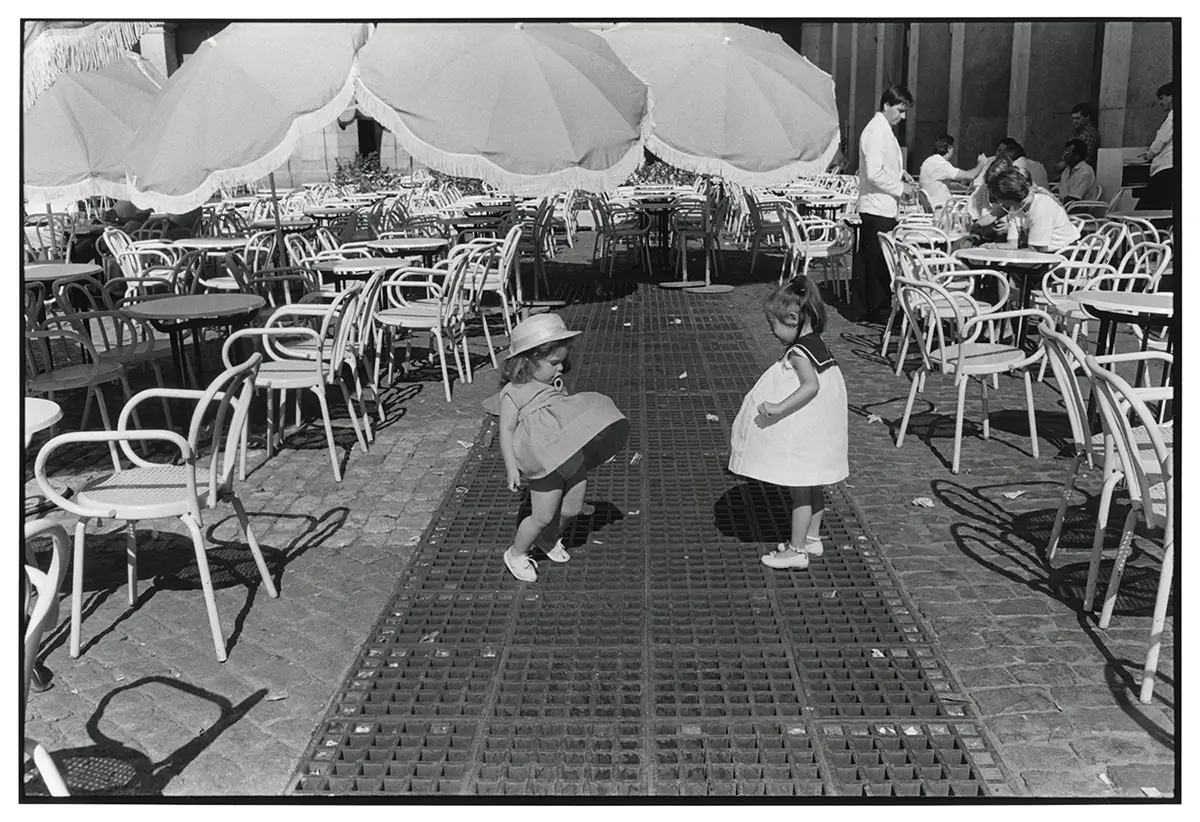

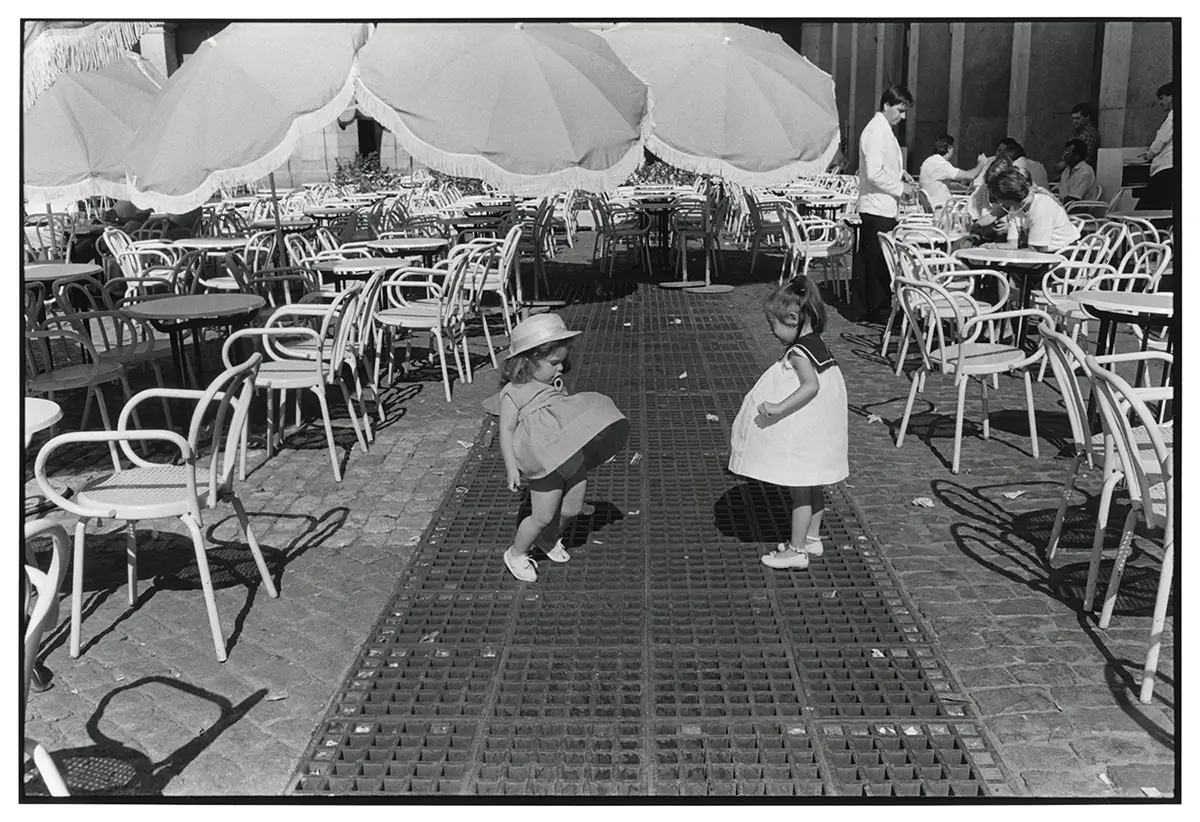

Plaza Real, Madrid, 1988 © Dona Ann McAdams

I shoot with a Leica because it is small and quiet and fits snugly in my hand. It can be a tool or a weapon, or both. I was lucky enough to be at a time and place in San Francisco in the early 1970s when the Leica was the tool amongst my photography friends, and they could be relatively easy to find.

Who, or what, are some of your major influences?

I was dyslexic as a child, but didn’t know it then. One of the things I found easy to understand were the funny pages, the comics in newspapers, that rectangle could tell a story. I found the thought balloons above the characters concise and pleasing, the frames and edges, how a cartoon strip (like strip of film) was easy to read. The visual and text together. I became obsessed with the cartoon Nancy by Ernie Bushmiller. Nancy as a young girl made sense to me. how she moved with ease in the world and didn’t seem to care about what others thought. She was her own person and didn’t seem to care how she looked. I also loved her partnership with Slugo, and the relationship she had with her beautiful aunt, Aunt Fritzie. Nancy soon morphed into other cartoons, especially underground comics in my teens. I would devour them. Justin Green, whose revelatory comic book, Binki Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary completely summed up my relationship to the Catholic Church. And then there was Little Nemo in Slumberland and picture books and illustration in general. All of it informed or primed my eye for photography.

As for photographers, I’d say the first two photo books I bought when I was twenty at a camera swap were Robert Frank’s The Americans, and a copy of Diane Arbus’ Aperture book. It was Arbus’ work I saw in high school on a field trip to MOMA that really changed my life. That body of work influenced not only the way I thought about what art was or art could do, but showed me that photography could be more than just taking pictures. That they could be a subtle, even beautiful, form of activism.

South 9th Street, Williamsburg, Brooklyn, 1979 © Dona Ann McAdams

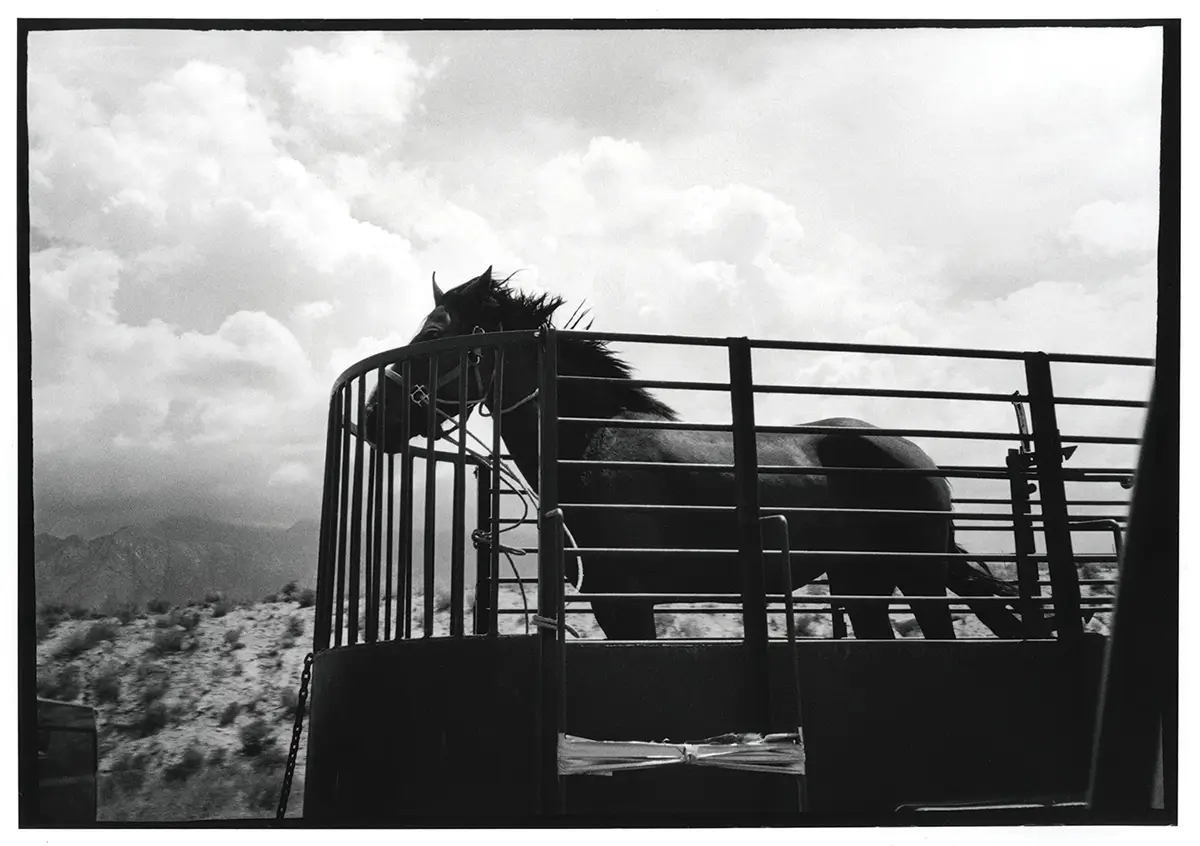

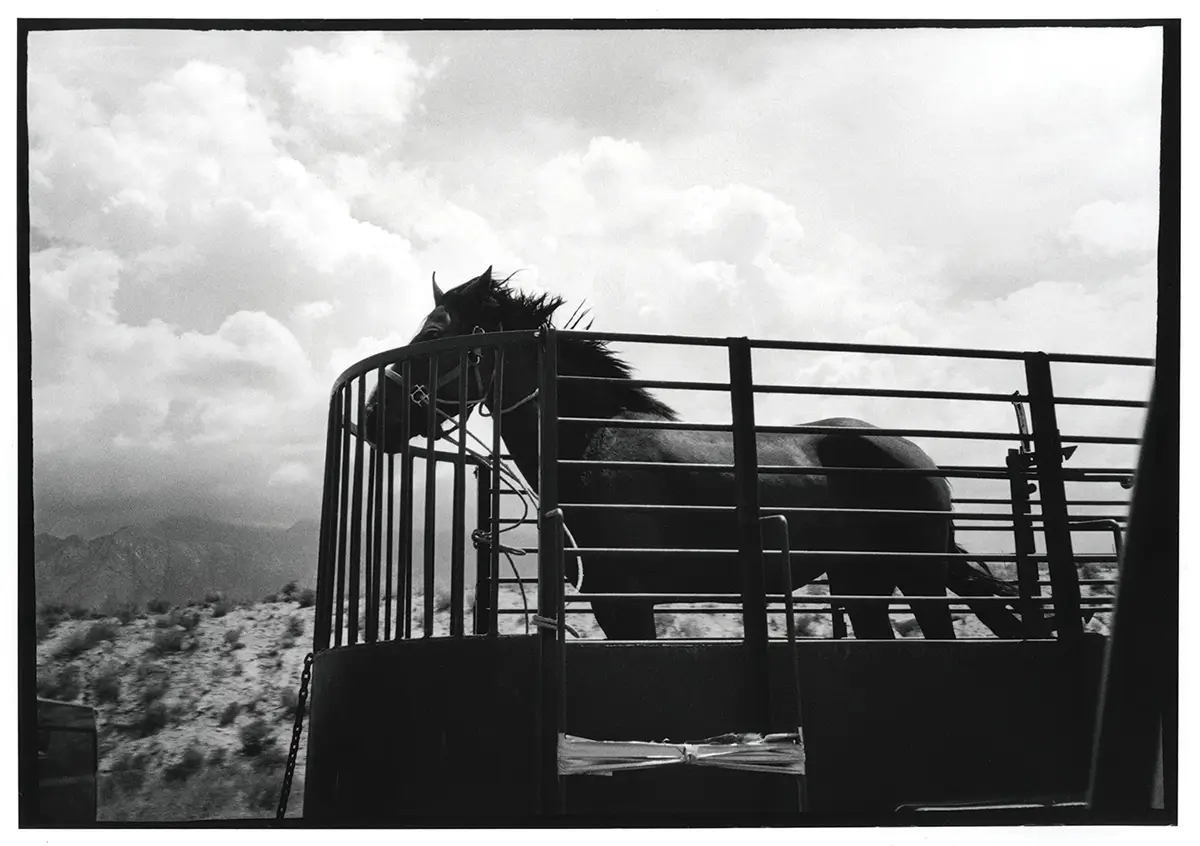

Highway 80, Nevada 1991 © Dona Ann McAdams

Both, but always an activist first.

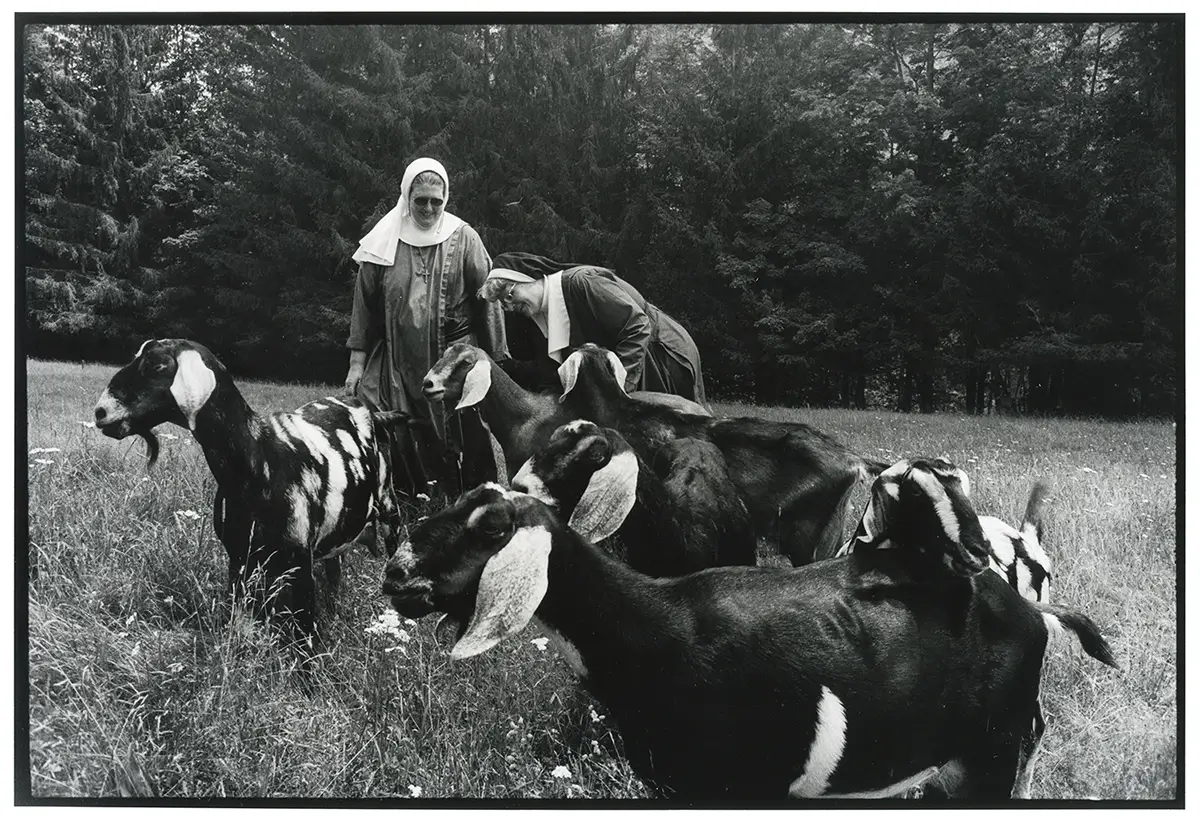

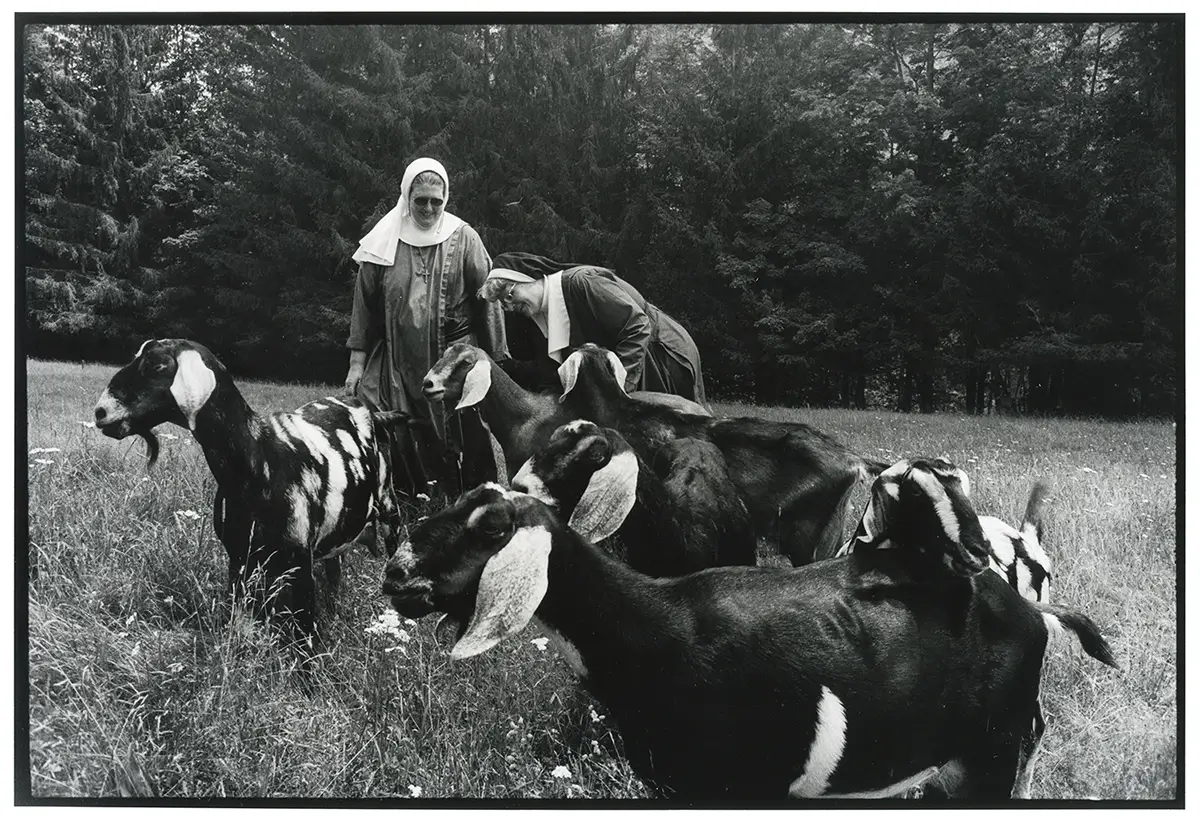

You live on a farm with goats and make cheese as well as make photographs. What does living on a farm have to do with your artwork?

Well, speaking of activism: it’s a form of active living, making your own food. But artistically, living around goats, doing chores, spending time with horses, having that intense non-verbal exchange that is deep and compassionate and intuitive is incredibly enriching and meaningful to me. It’s another non-verbal way of seeing and being. Just as photography is too. I prefer the company of animals to just about anyone. They allow me to stop and listen and be.

Why do you work in black and white?

I like the abstraction of black and white. The relationship of light and dark. I see in color, but I feel in black and white.

What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a portfolio called “Searching for Sheela.” I’m photographing medieval and older forms of vaginal imagery, the ancient Sheela na gigs found at sacred sites, in church architecture, and various historic monuments all over the world, but specifically in Europe, and even more specifically in Ireland. The Sheela na gig is a figurative carving of naked female form displaying an exaggerated vulva. They’ve been around since prehistory, and often accompanied places of feminine power. I’m going on a pilgrimage searching for them in Europe and Ireland. The project is a kind of bookend to a similar one I did in my early twenties when I drove across the country photographing nuclear power plants, and often putting myself in the picture. The Nuclear Survival Kit (1980) was my own wry critique of the man-made nuclear power industry and its dangers. “Searching for Sheela” will be a celebration of women’s generative power.

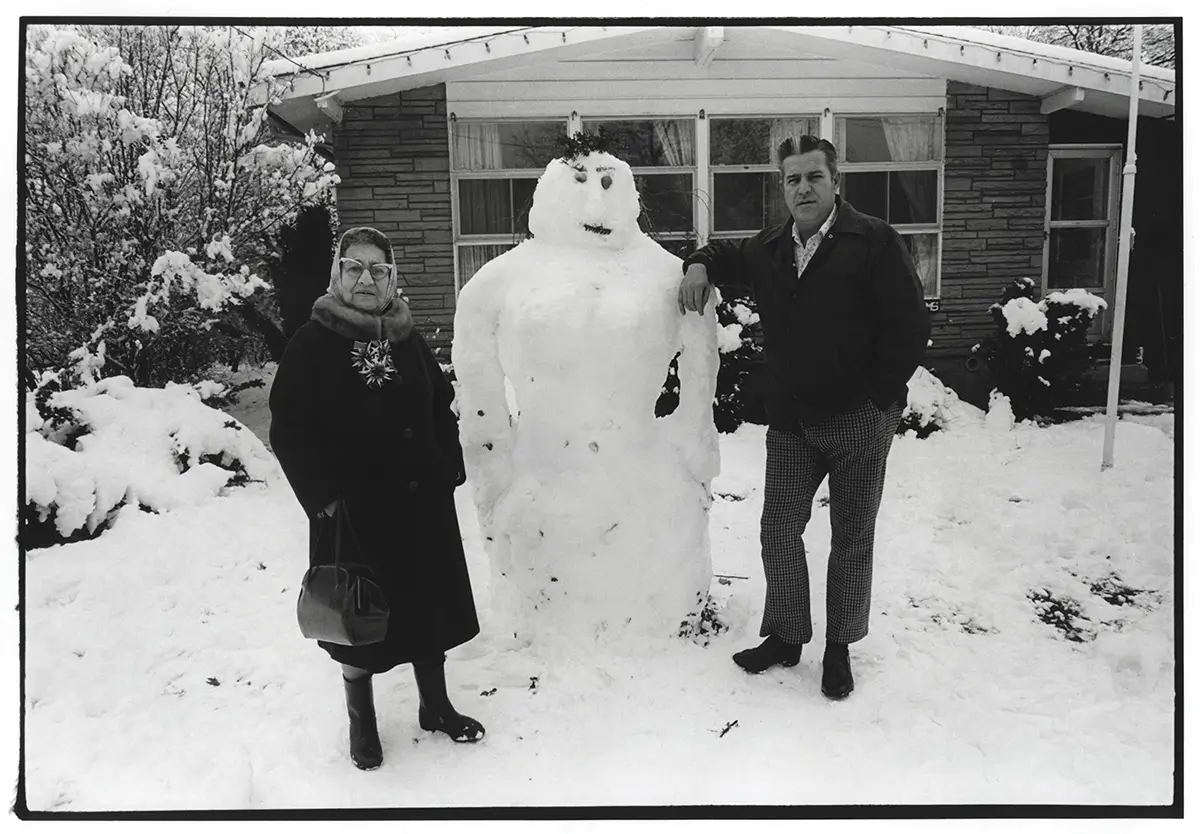

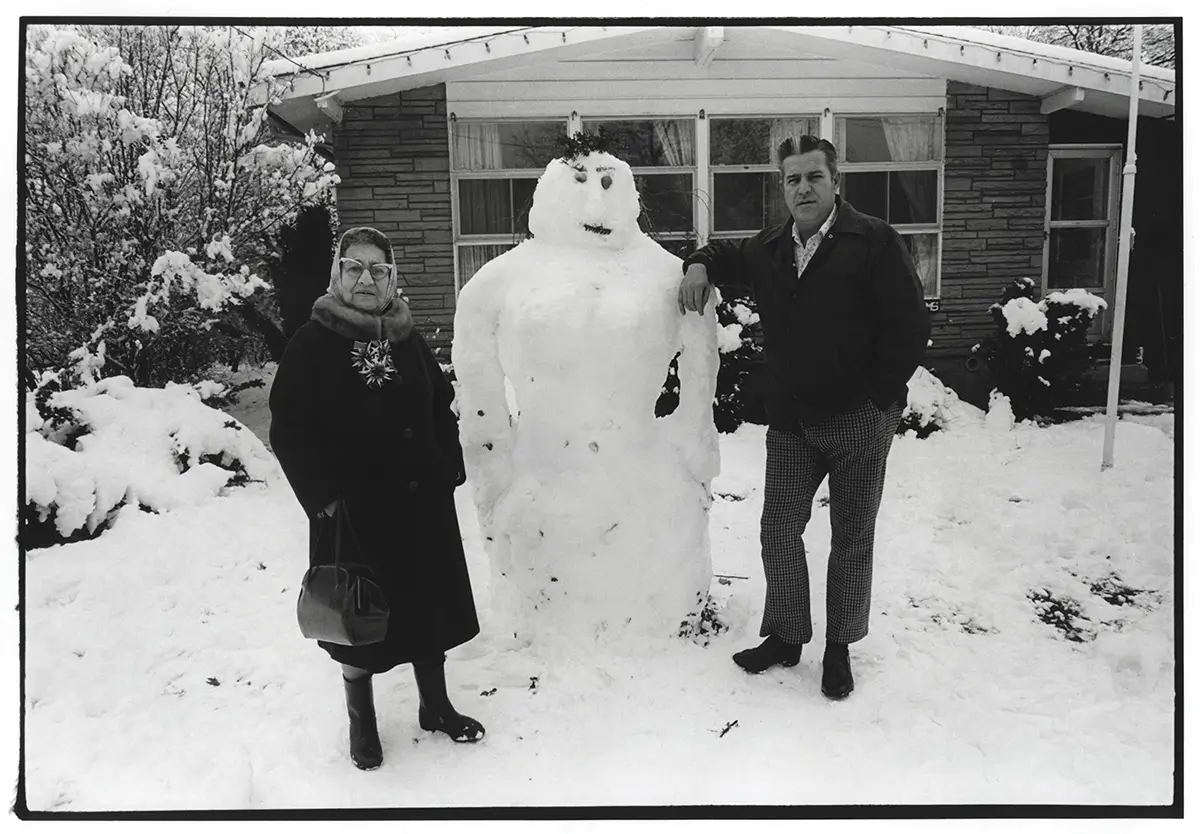

Lillian and Don, Lake Ronkonkoma, NY, 1977 © Dona Ann McAdams

.

Objects for me are loaded with energy and meaning. As a child I always felt loved but not always understood. My collecting things was a way for me to have a family that understood me. I’ve collected different things throughout my life. They change as I change. There’s often no rhyme or reason but there are some consistencies: Buttons. Hankies. Beach tiles and, of late, old bowling balls. For me collecting, or “thrifting” as it’s called today, is a kind of therapy. Hunting and gathering. A social practice. Recycling for pleasure. Curating the elements of the world. It’s not unlike what I do with photographs: curating light and form and time.

I have to ask this one. Sorry. What’s your favorite kind of sandwich?

Ice cream.

Nuns of St. Mary’s on the Hill, Northern Spy Farm, Sandgate, Vermont, 2015 © Dona Ann McAdams

On the rail, Saratoga Racecourse, Saratoga Springs, NY, 2013 © Dona Ann McAdams