Asiya Al Sharabi is a Yemeni-American visual artist whose work has been recognized both nationally and internationally. She began her career as a journalist and photographer before shifting her focus to artistic photography, using her lens to explore the complexities of identity, culture, and migration. Now based in the U.S., her work is deeply rooted in the experiences of Middle Eastern women, young adults, and immigrants—themes that continue to shape her creative vision.

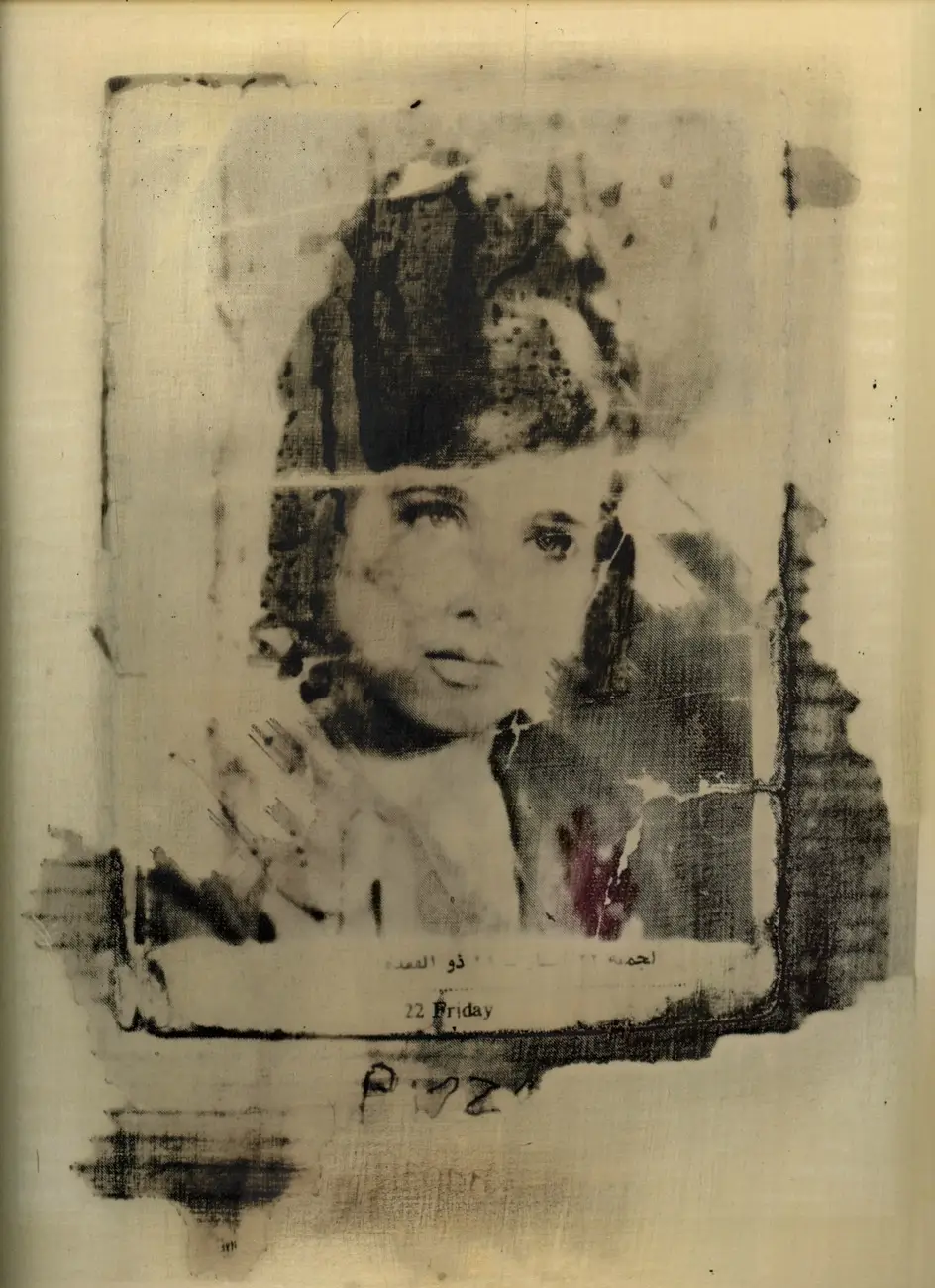

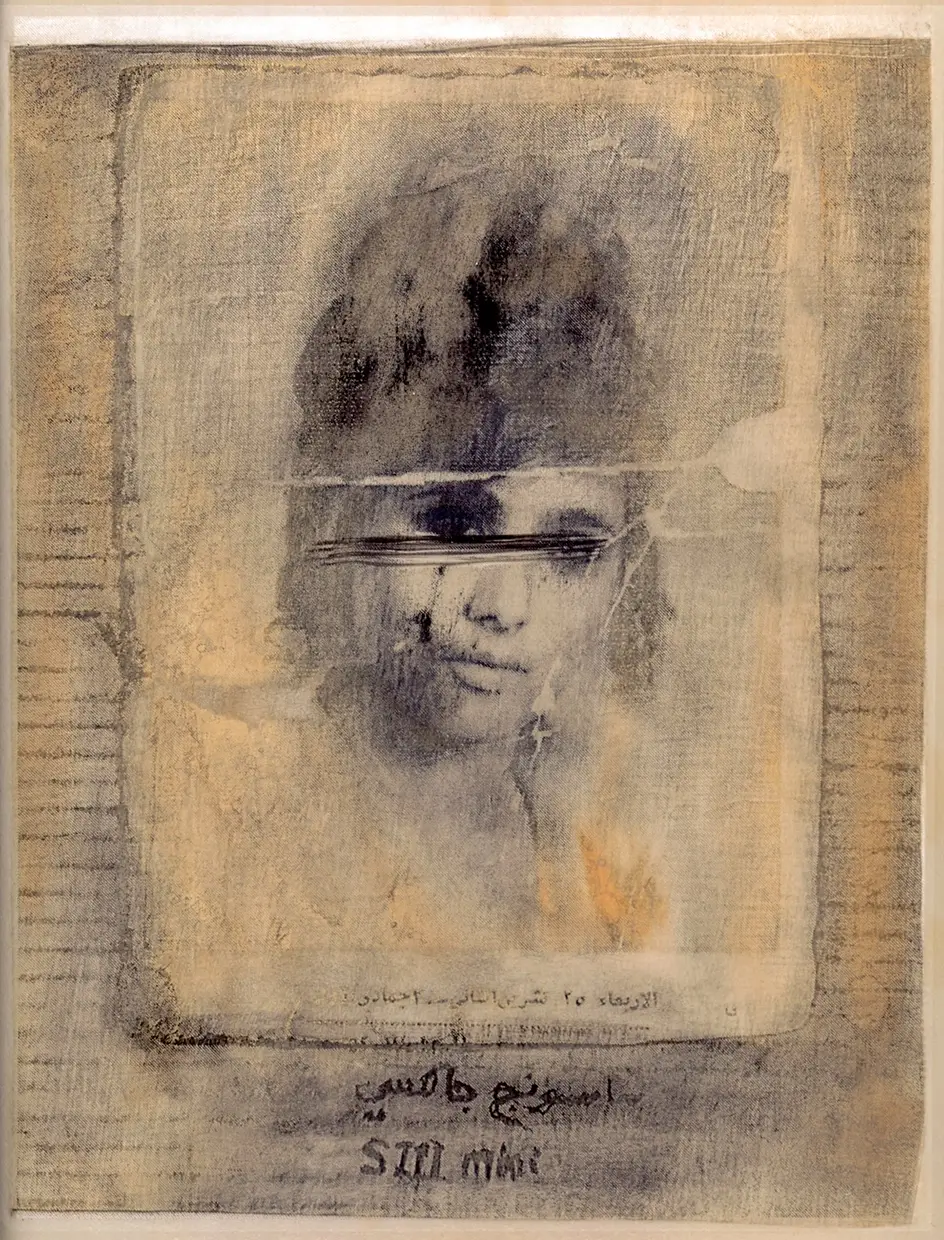

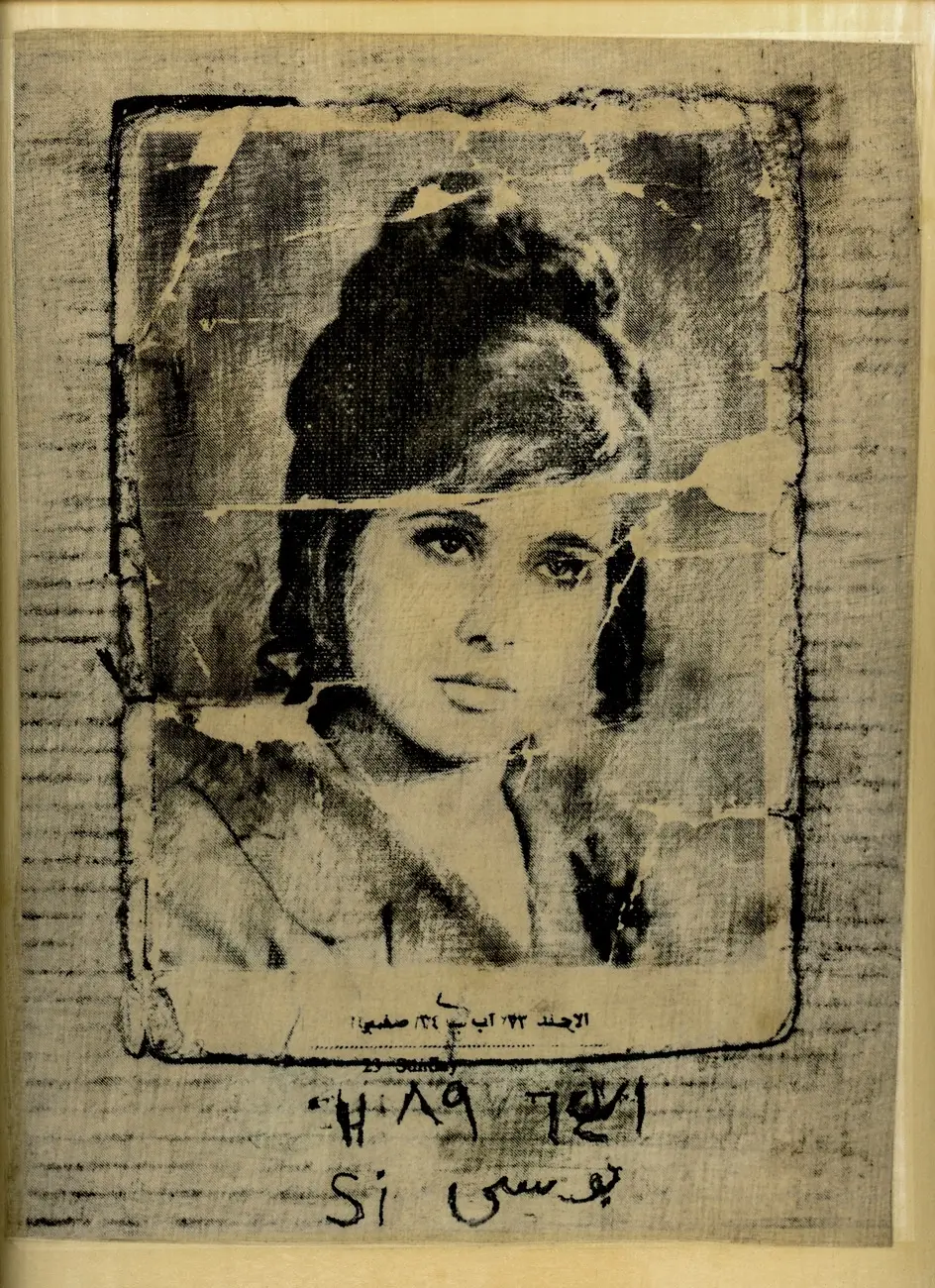

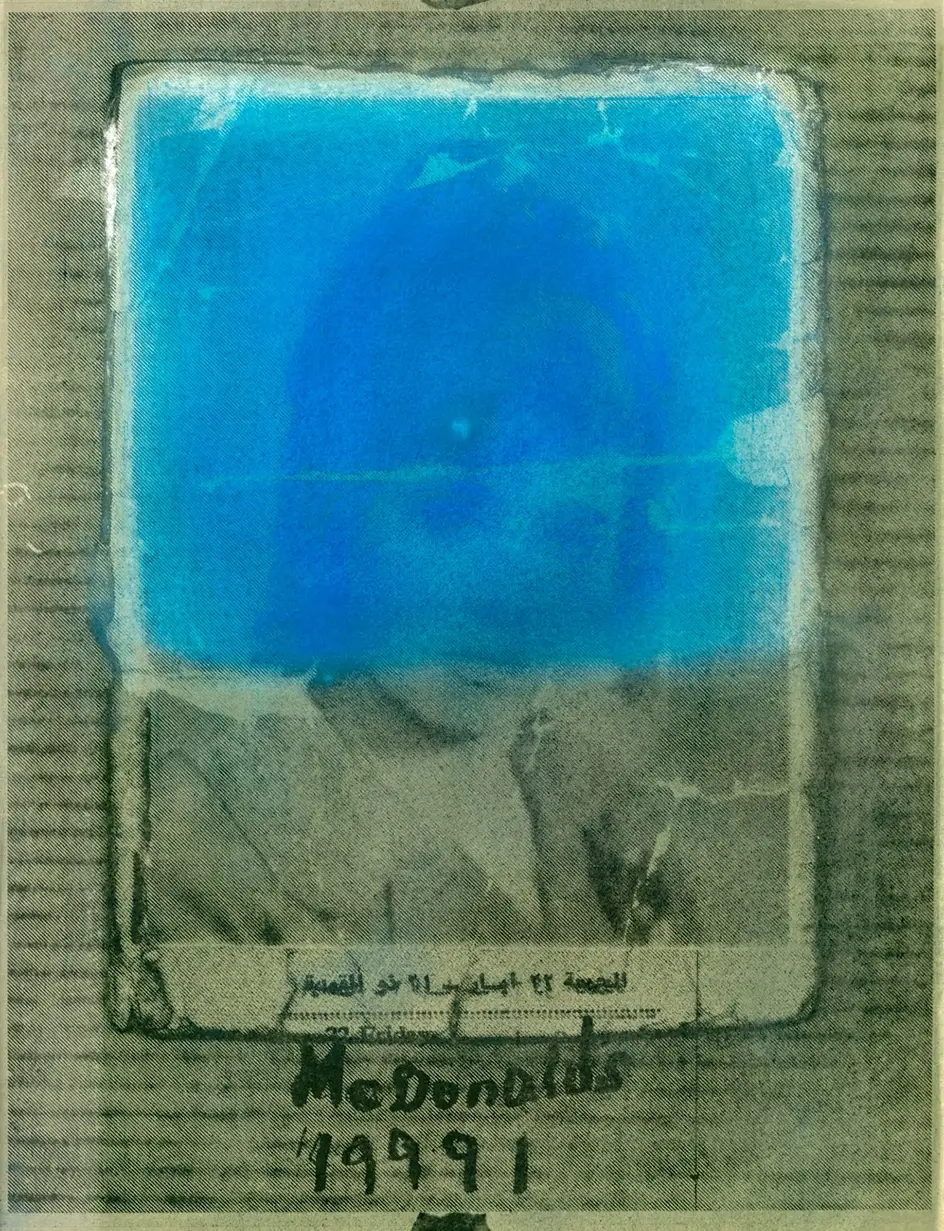

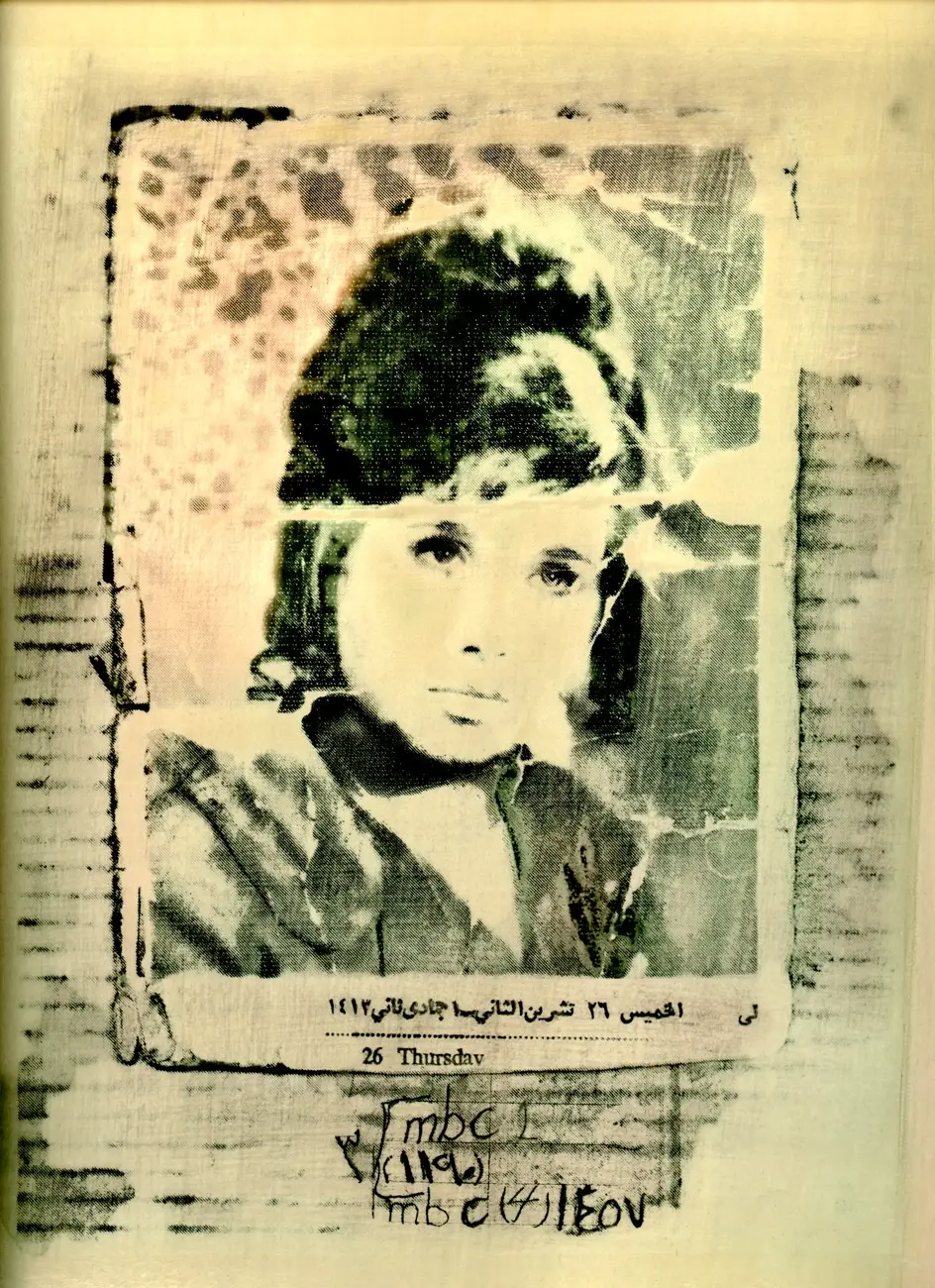

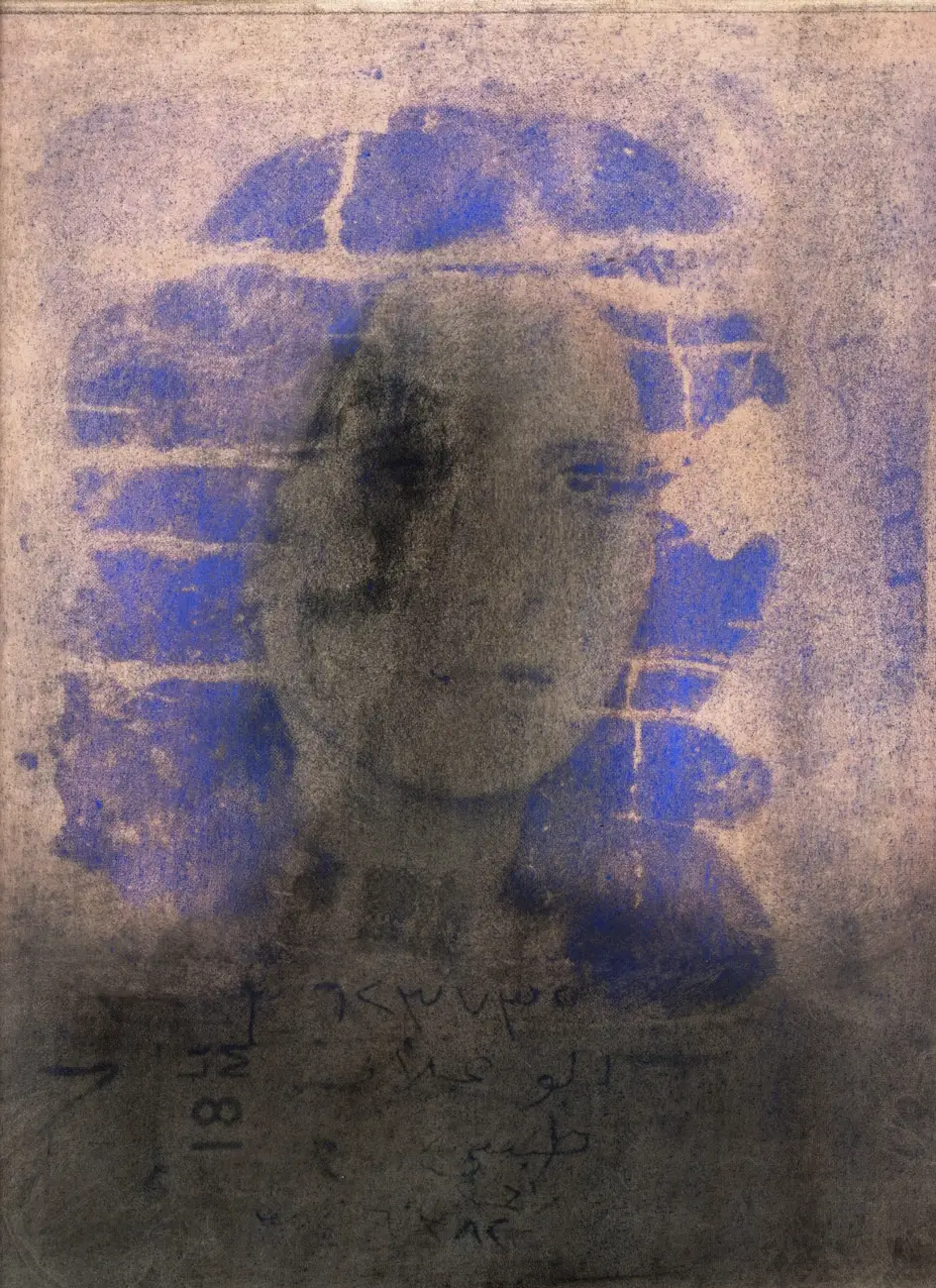

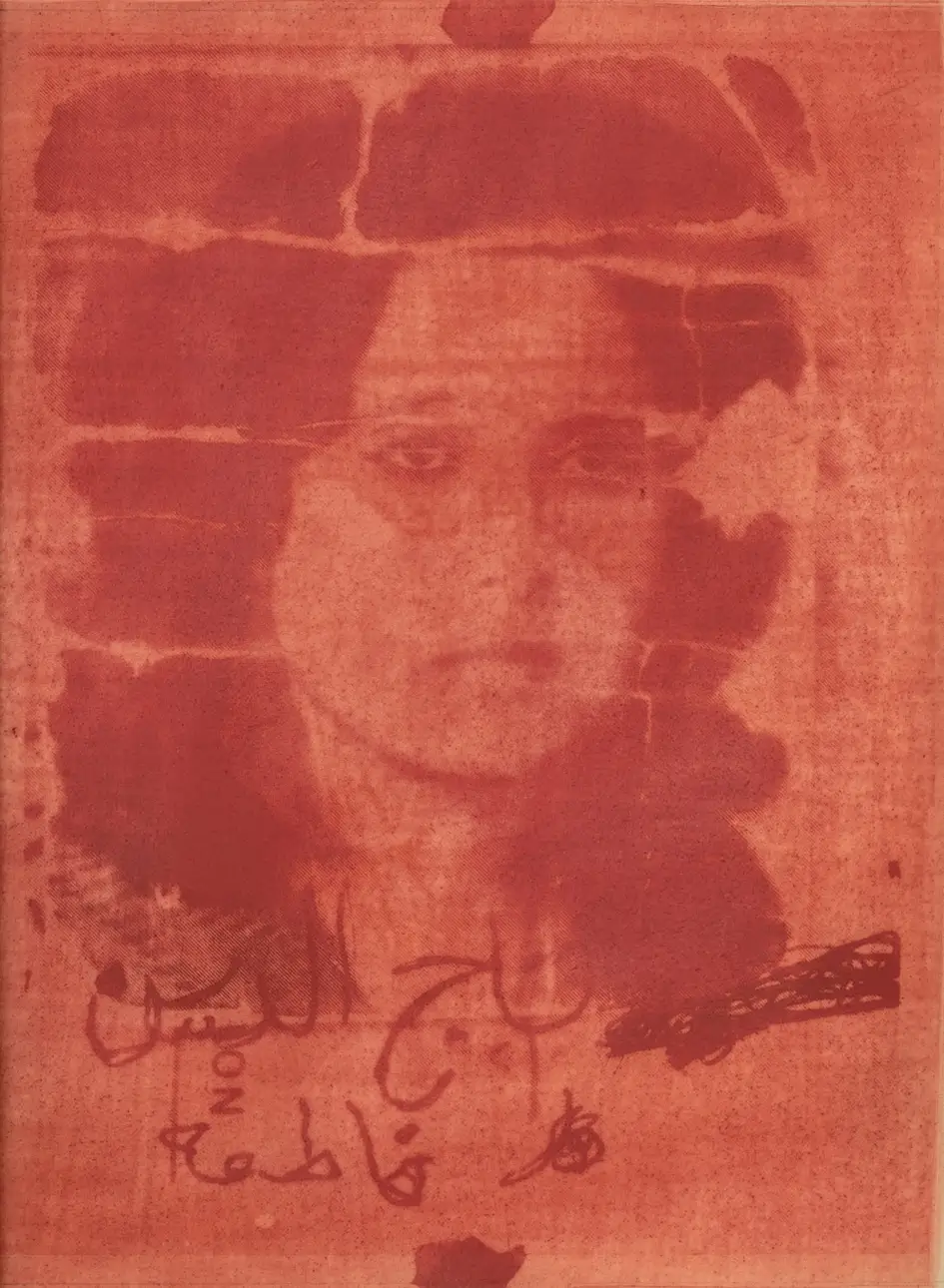

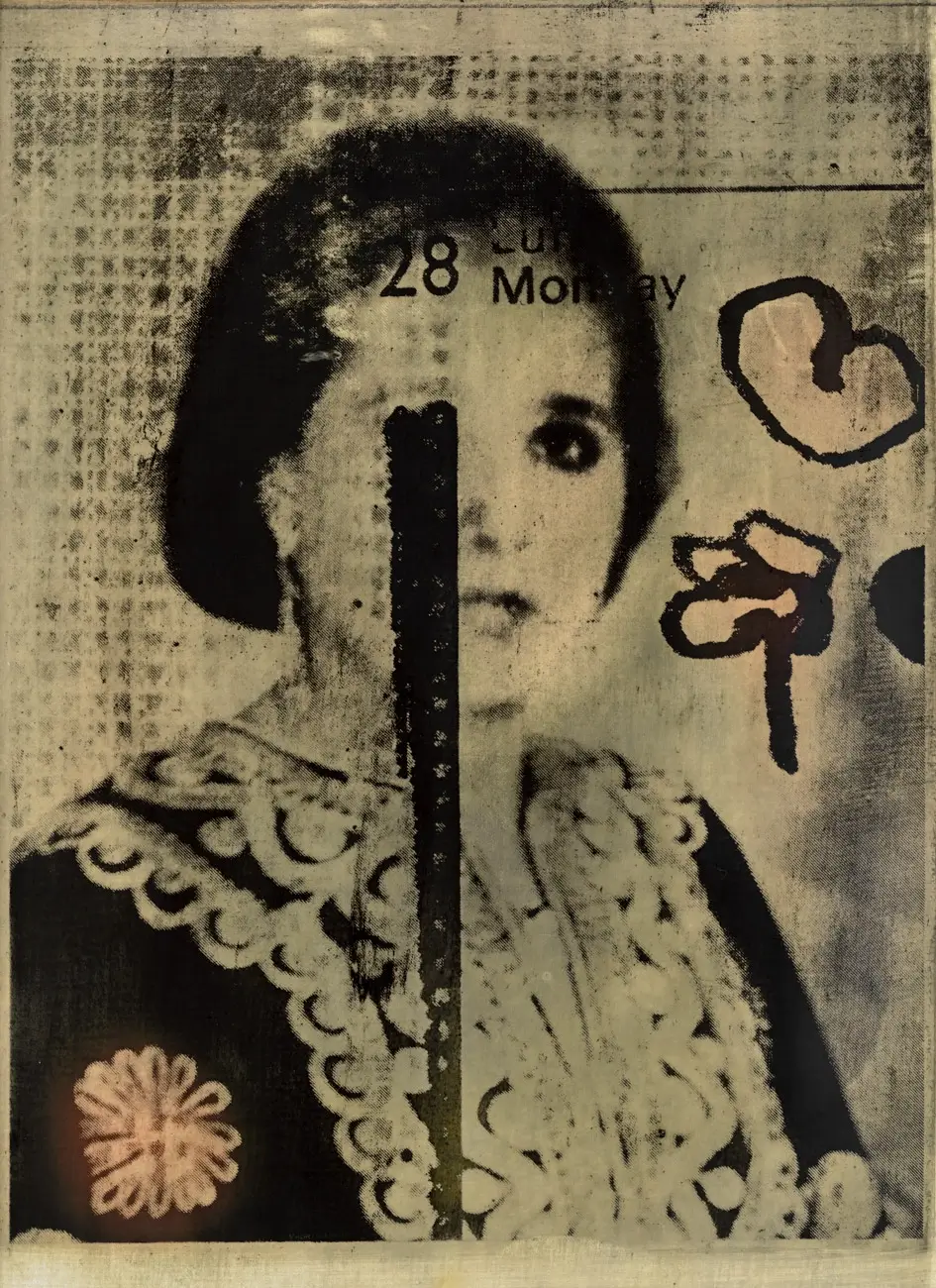

Her artistic expression extends beyond traditional photography, incorporating alternative photographic processes, collage, and inverse negative prints. These techniques not only add a distinct visual depth to her work but also serve as a means to examine the intersection of politics, culture, and religion in shaping personal and collective identities.

Her project My Mother's Tender Script further reflects her commitment to telling deeply personal yet universally resonant stories and earned her the

February 2024 Solo Exhibition.

We asked her a few questions about her life and work.

All About Photo: Can you tell us about your journey into photography? What initially sparked your interest?

Asiya Al Sharabi: What drew me most to photography was the freedom it offered—the freedom to create something entirely my own. As a woman in a society where choices are often dictated or denied, that freedom felt revolutionary. Photography gave me the power to frame a moment, to tell a story on my own terms, and to capture what is often unseen. What it reveals always evokes what it conceals, adding layers of meaning that go beyond the image.

I began my journey in photojournalism, driven by a deep passion to document and share stories that mattered. I wanted to capture the truth and bring attention to voices that might otherwise go unheard. But over time, I felt constrained by the urgency and limits of journalism. I longed for a slower, more personal exploration of storytelling, one where I could fully immerse myself in creativity.

That’s when I turned to fine art photography.

How did you develop your unique photographic style, and what influences have shaped it over the years?

My style developed through persistent searching and experimenting. Artists like Frida Kahlo, Cindy Sherman, and Andy Warhol, as well as my upbringing in a traditional society, have influenced how I create and tell stories.

What role do you believe photography plays in preserving personal and cultural histories?

Photography is both a time capsule and a witness. It captures what words often fail to describe and preserves the essence of a moment, allowing it to live beyond its time. It doesn’t just document history—it humanizes it, connecting faces, emotions, and experiences to larger cultural narratives.

For me, photography is about honoring what might otherwise be overlooked. It’s a way of saying: This mattered. This deserves to be seen. It bridges the gap between personal memory and collective history, reminding us of our shared humanity.

What inspired you to create My Mother's Tender Script, and how did the concept first come to life for you?

Death. Pain. Longing.

These emotions drove the first phase of this project. After my mother’s passing, I found myself holding onto her handwritten notes in her phone notebook. Her words felt like echoes of her voice—a voice shaped by a life of early marriage, widowhood, illiteracy, and her second marriage to my father, who was much older and more educated. Despite these challenges, her notebook became her bridge to his world, a testament to her quiet determination.

What began as a way to honor her spirit became something larger—a reflection of the broader experiences of women in Yemen and the Middle East.

Can you describe your mother’s influence on your art and how her life story shaped your creative process for this project?

After my mother’s passing, I found myself yearning for a lifeline—a bridge that could reconnect me with my studio and my art. I thought about how she, despite being illiterate, created her own bridge to the world and to my father, an educated writer, through her phone notebook. If she could build that connection, I knew I could do the same for myself through my work.

Her notebook became a guide for me. It held her voice, her determination, and her attempts to navigate a life of challenges. This project became my bridge back to creation, just as her notebook was her bridge to possibility.

Why did you choose to work with the Resino-Pigmentype technique, and how did this historical process align with your mother’s story?

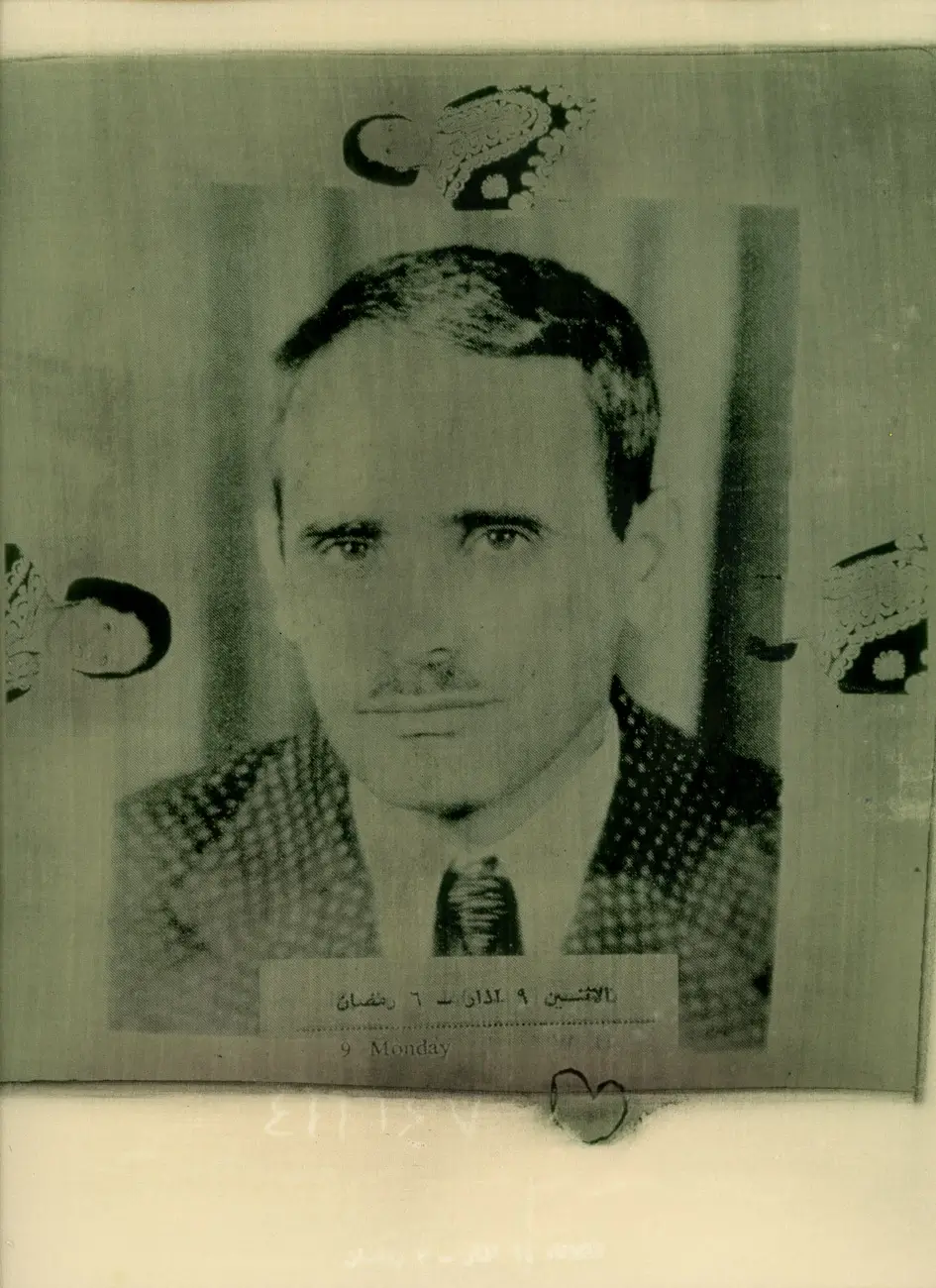

This technique felt deeply connected to my mother’s story. Its layered, tactile quality mirrors the complexity of her life, while its historical roots honor the endurance of traditions—much like the traditions she upheld while navigating her own challenges.

The process itself—a careful blend of painting, printmaking, and photography—allowed me to bring her handwritten notes and drawings to life. As I brushed the pigment onto her image and watched it emerge from negative to positive, it felt as though I was bringing her back to life, layer by layer. Each step became a healing act, embedding her essence into every print.

What challenges did you face while working with historical photographs and archival material, especially when transforming them into contemporary pieces?

Each image and text felt important, especially since most of the series uses the same image repeated in different ways. The process of working with chemicals, exposure, and layering was delicate and time-consuming, often taking days. Sometimes, a small mistake—a chemical imbalance or an unintended mark—would ruin the result, forcing me to start over. It was a challenging but rewarding process, requiring patience and precision to bring the past into a new light.

As you reflect on your mother’s life, what aspects of her resilience and strength stand out to you the most?

Her ability to navigate life with resourcefulness despite her illiteracy and challenges stands out to me the most. She transformed her phone notebook into a tool of empowerment, using it to bridge the gap between her world and others, including my father’s. Her determination to adapt and create solutions for herself, even without formal education, continues to inspire me.

What do you hope viewers will take away from My Mother's Tender Script?

I hope viewers walk away with a deeper sense of empathy and understanding. While this series honors my mother, it also sheds light on the lives of countless illiterate Yemeni women who still face these struggles today. Their stories remain untold, yet they hold truths about strength, endurance, and the human spirit that deserve to be seen and heard.

What equipment do you use?

I use a Canon DSLR, for capturing contemporary elements of my work. For a more tactile and intimate approach, I rely on my Hasselblads—one for film and one for digital—allowing me to seamlessly bridge the analog and digital worlds.

For printing, I rely on tools essential for the Resino-Pigmentype technique, including heavy-weight watercolor paper, sensitive chemicals, UV light exposure units, and fine dry pigment powders.

Do you spend a lot of time editing your work?

I keep my edits simple and minimal, as I value the purity of the photo—its rawness and originality. I’m not an expert in Photoshop, nor do I aim to be, because I believe over-editing can take away from the authenticity of an image. Instead, I spend most of my time in the studio or the darkroom, where the creative process feels more hands-on and connected to the essence of my work.

Are there any upcoming projects you’re working on that continue themes of memory, family, or personal history?

Yes! I’m currently working on turning My Mother’s Tender Script into a book. As for my next project, I prefer to let it take shape before sharing more, but it will continue to explore themes of personal history and society.

How do you see your photography evolving as you continue to explore both personal and universal narratives?

Ever unfolding.

Anything else you would like to share?

My Mother’s Tender Script is more than a personal story; it’s a tribute to women whose lives often go unnoticed. Through this work, I hope to spark conversations about literacy, identity, and the silent strength carried by so many Yemeni women. It’s a reminder that even in the face of challenges, their stories are worth telling and preserving.