I first met

Norm Diamond at the

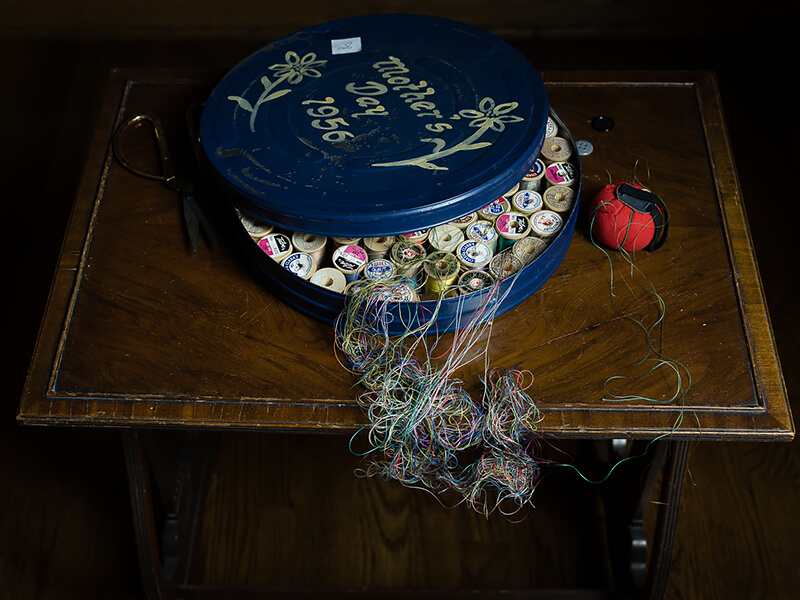

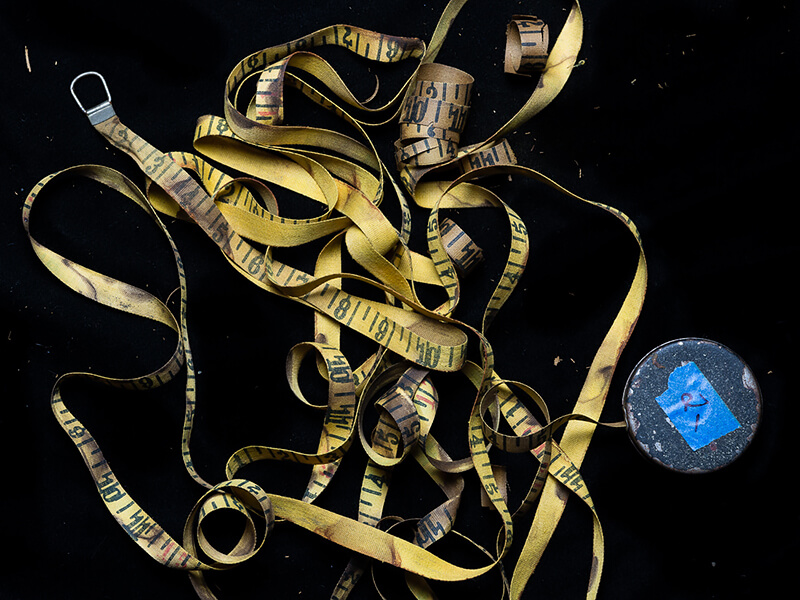

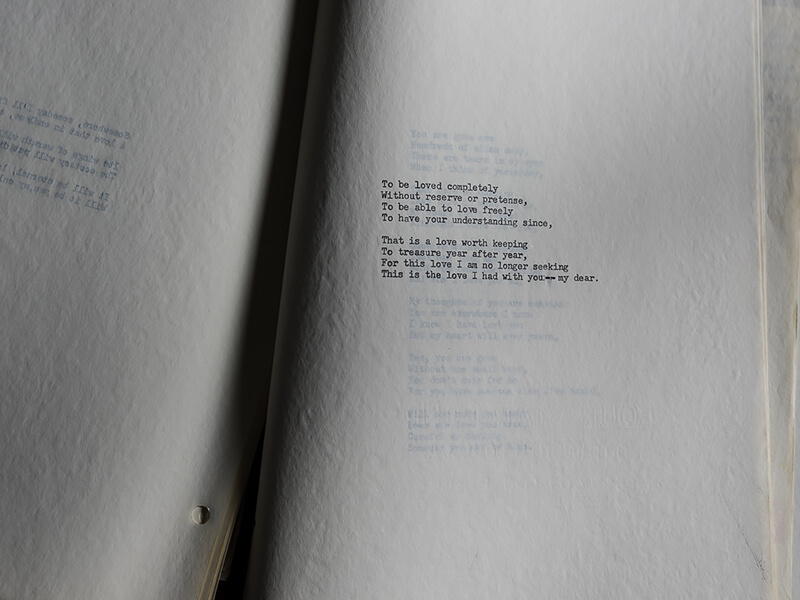

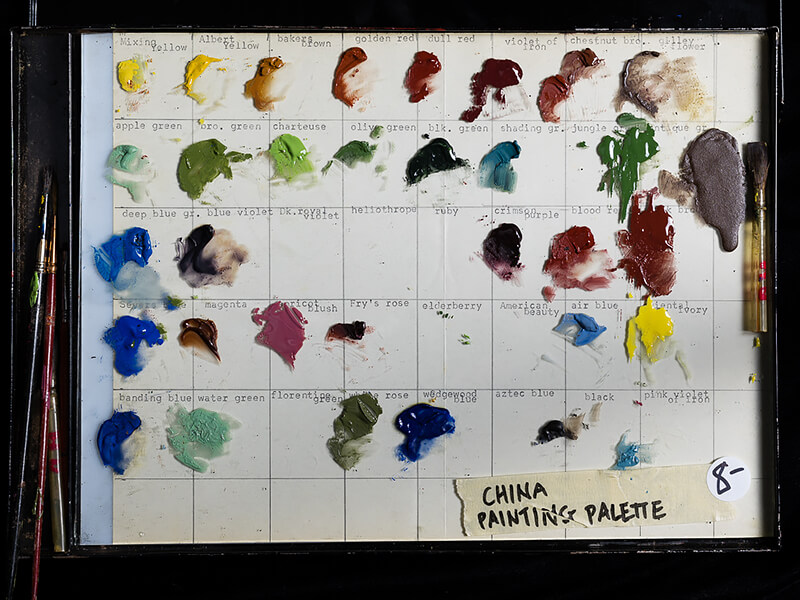

PhotoLucida portfolio reviews in Portland, Oregon, in 2015. He had a number of prints of beautiful still lifes and interiors, the color palette perfect, the spaces familiar, the objects loved and worn. And yet there was something strange about the pictures. Each precious object, each gilt-framed photograph, each hand-made train layout, each broken toy, had a price tag on it. The man of the house pictured in a tuxedo on the bedside table, just $2. A gauzy nightgown, very much like the one my mother still wears today, back lit from a window and sheer as sheer can be, $15. A circular tin like a movie reel case holding spool after spool of unraveling thread, somehow symbolic of our unraveling lives, a mere $8. It's really too much, especially when you come to the personally typed widow's poem or to a palette covered in paint dabs applied by someone's brush, someone who is presumably no longer with us.

I feel like a voyeur. I also feel like I've been let in on a secret. I feel something akin to nostalgia too. I want to go to those places that Norm Diamond is visiting, walking through these homes with his camera and his heart and seeing what's been left behind. Also, seeing that everything has a price. Sometimes it's funny, like seeing a crooked toilet paper dispenser up for grabs, the price written in marker on the wallpaper, or someone's lifetime supply of Playboy magazines stacked and labeled by era or decade. Sometimes it's more mysterious, like a closet full of identical hats. Or other times poignant, with a padded suitcase full of multi-colored 45 records, precious enough to be locked away, but not so beloved as to be kept by the next generation.

I think of my own parents who keep nothing. They are purgers. I know that's not a word, but they like to purge their belongings. Each time I go home, the house is more and more empty. They have a basement that's as big as the entire house. The only thing down there is a blender. A blender, that's it. I look at the spaces where our skis were or our upright piano or my Weeble Wobble circus (who wouldn't remember that with a sigh), and wonder where it all went. (I'm actually certain the Salvation Army has it all). I finally had to say something on my last visit home. Something similar to this, Could you please leave one book shelf or even better, a room, for me to go through and have a memory or two and a laugh and a cry after you die? They've obliged, though this act alone might kill them.

Anyway, I digress. Norm Diamond's pictures have brought me back to my childhood, to what used to be, to what could have been. I'm not the only one who was taken by his images at that portfolio review in 2015. The publishers at Daylight books were also moved by the project, moved enough to design and publish Diamond's book, What Is Left Behind. I got to see a copy at PhotoLucida in 2017 and it is a beauty, full of heartache and humor and love and loss and all the other stuff of life. It took a few years, but it was worth the wait to revisit the work and see it collected in a bound edition.

Here is what the artist had to say about his project and his process:

Estate Sales have become a common way for people to dispose of their parents' possessions after they die or move to assisted living facilities. For over a year I went to several hundred estate sales in Dallas, where I live. In addition to photographing at the sales themselves, I also bought many inexpensive items that I studied in my home studio.

Several themes have emerged from this work. The stark reality of life's brevity pervades every estate sale, where children's toys sit a few feet from wheelchairs. Unique personal possessions tell the often poignant stories of people I never knew and could only wonder about. I also discovered knickknacks that offer fascinating commentaries on our culture and politics. Every weekend at just about every sale, I saw sadness, irony, history, and humor. The objects at these sales will find a rebirth of sorts in the homes of their new owners, but also hopefully in these photographs.

Estate sales also evoke strong emotional connections to my past. They make me think of my parents and the treasured belongings they left for my sister and me. I reflect upon my mortality, the choices I have made, and the dreams I never pursued. And, I wonder what my estate sale will look like.

Six of Norm Diamond's prints from this series will be in the Currents exhibit from December 7th, 2017 to February 4th, 2018 at the

Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans. The opening reception is December 8th during

PhotoNOLA weekend. Don’t miss a chance to see his work in person!

Biography

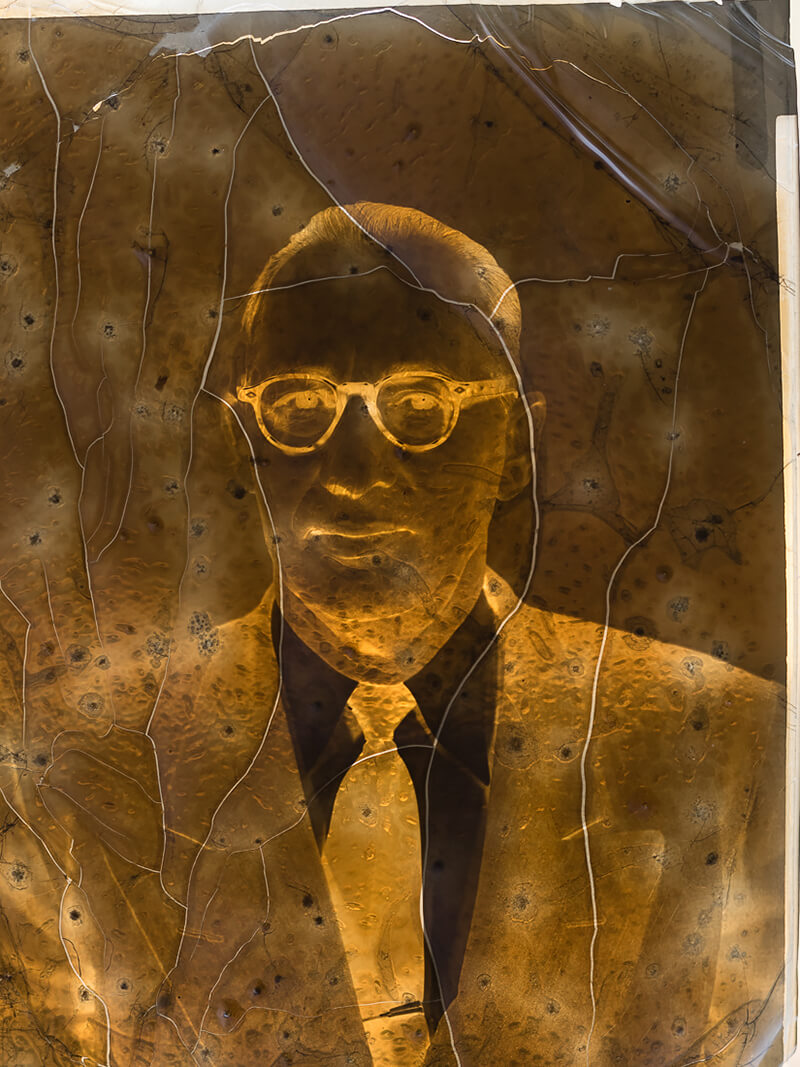

Norm Diamond spent over a year photographing estate sales in Dallas, Texas, where he lives. Daylight Books published a monograph of this work, What Is Left Behind—Stories from Estate Sales, in May of 2017. Prints from this series have been shown at the Houston Center for Photography, the Davis Orton Gallery in Hudson, New York, and at the Griffin Museum of Photography in Winchester, Massachusetts. From May 20 – July 12, 2017, the

Afterimage Gallery in Dallas, Texas, hosted a solo show with sixteen prints from this work.

Based on this series, he was named a finalist in the 2015 and 2016 Photolucida Critical Mass competitions. Pictures from his previous projects have been exhibited in juried group shows including at the A. Smith Gallery in Texas, PhotoPlace Gallery in Vermont, The Center for Fine Art Photography in Colorado, as well as several online galleries.

Diamond is now a fulltime fine art photographer after having had a long career in interventional radiology. He has studied with Debbie Fleming Caffery, Sean Kernan, Keith Carter, Arno Minkkinen, Aline Smithson, and, from 2013 to the present, he has been mentored by Cig Harvey. In addition to his teachers, he attributes much of his success in photography to his experiences as a physician.