Gertrude Käsebier was an American photographer. She was well-known for her images of motherhood, portraits of Native Americans, and promotion of photography as a career for women.

Käsebier was born Gertrude Stanton on May 18, 1852, in Fort Des Moines (now Des Moines, Iowa). Her mother was

Muncy Boone Stanton and her father was

John W. Stanton. He brought a sawmill to Golden, Colorado, at the start of the Pike's Peak Gold Rush in 1859, and he profited from the building boom that followed. Stanton, then eight years old, traveled to Colorado with her mother and younger brother to join her father. That same year, her father was elected as the first mayor of Golden, Colorado Territory's capital at the time.

After her father died unexpectedly in 1864, the family relocated to Brooklyn, New York, where her mother, Muncy Boone Stanton, opened a boarding house to support the family. Stanton lived in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, with her maternal grandmother from 1866 to 1870, and she attended the Bethlehem Female Seminary (later called Moravian College). Little else is known about her childhood.

She married twenty-eight-year-old

Eduard Käsebier, a financially secure and socially well-placed businessman in Brooklyn, on her twenty-second birthday in 1874. Frederick William, Gertrude Elizabeth, and Hermine Mathilde were the couple's three children. In 1884, they relocated to a farm in New Durham, New Jersey, in search of a healthier environment for their children to grow up in.

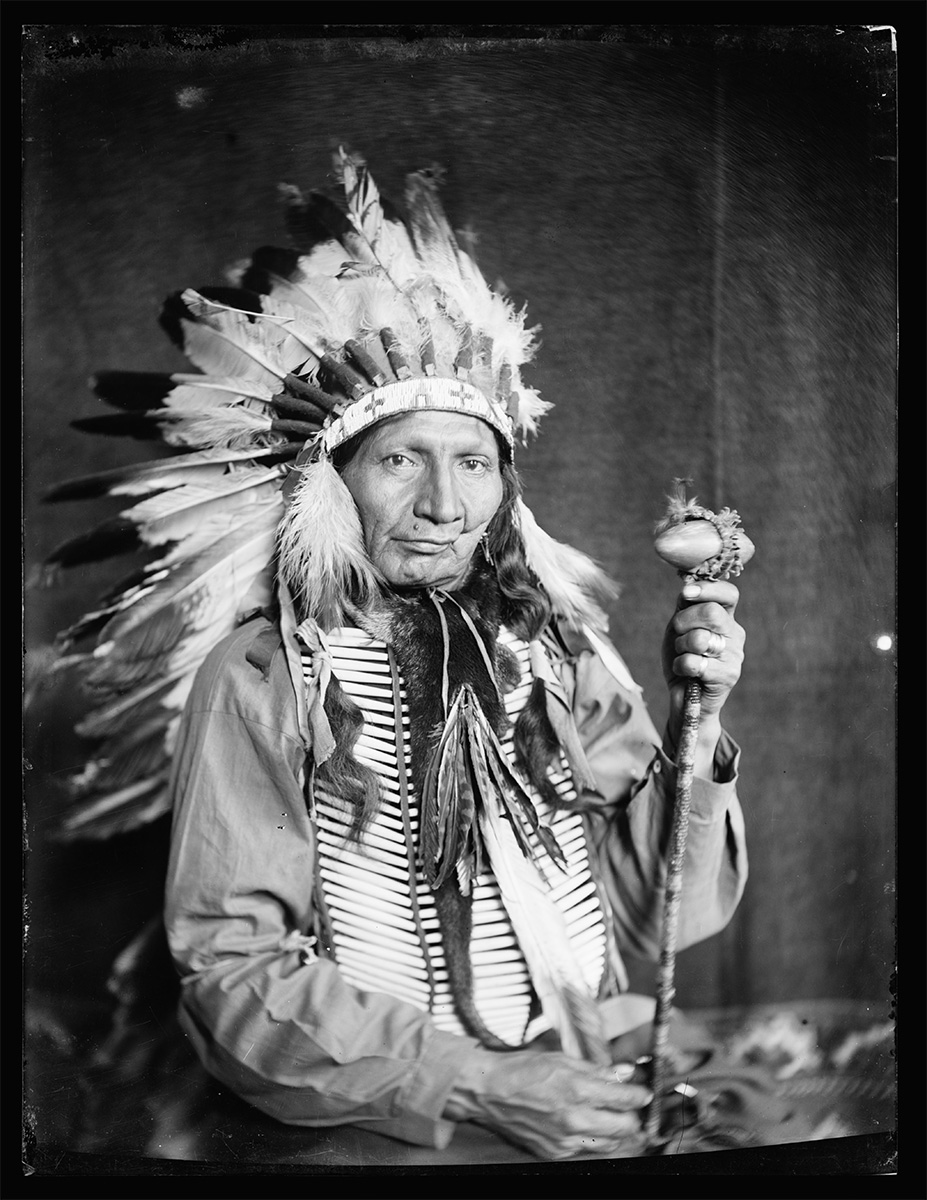

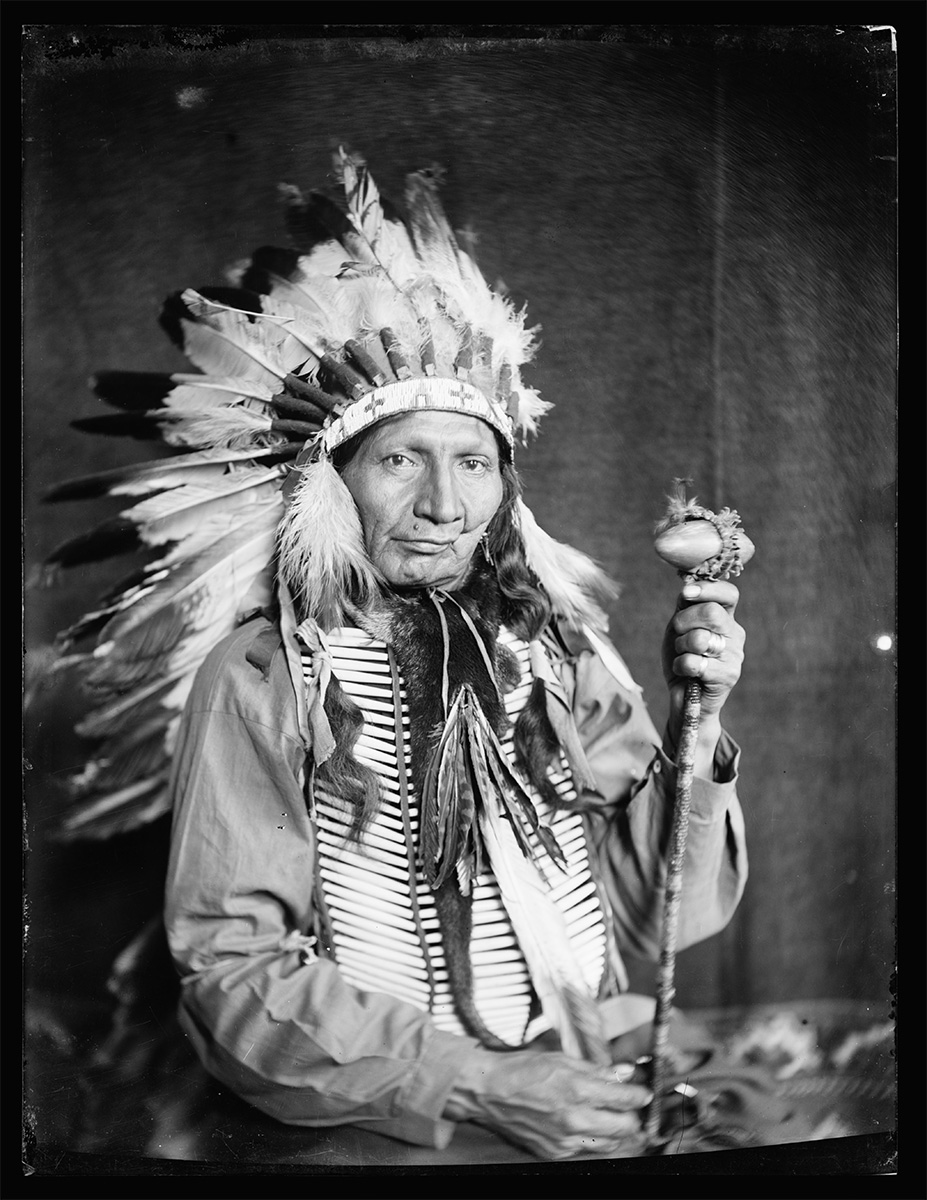

Flying Hawk, American Indian, c. 1900, U.S. Flying Hawk, American Indian, c. 1900, U.S.

Library of Congress © Gertrude Käsebier

later wrote that she was unhappy for the majority of her marriage. She stated,

"If my husband has gone to Heaven, I want to go to Hell. He was terrible... Nothing was ever good enough for him." Divorce was considered scandalous at the time, so the couple remained married while living separate lives after 1880. This unhappy situation later inspired one of her most strikingly titled photographs,

Yoked and Muzzled – Marriage (c. 1915), which depicts two constrained oxen.

Despite their differences, her husband financially supported her when she began art school at the age of 37, at a time when most women of her generation were well-established in their social positions. Käsebier never explained why she chose to study art, but she did so wholeheartedly. Over her husband's objections, she relocated the family to Brooklyn in 1889 to attend the newly established

Pratt Institute of Art and Design full-time. Arthur Wesley Dow, a highly influential artist and art educator, was one of her teachers there. He later assisted in advancing her career by writing about it and introducing her to other photographers and patrons.

The key to artistic photography is to work out your own thoughts, by yourselves. Imitation leads to certain disaster. New ideas are always antagonized. Do not mind that. If a thing is good it will survive. -- Gertrude Käsebier

Gertrude Käsebier studied the theories of

Friedrich Fröbel, a nineteenth-century scholar whose ideas about learning, play, and education inspired the creation of the first kindergarten. Käsebier was greatly influenced by his ideas about the importance of motherhood in child development, and many of her later photographs emphasized the bond between mother and child. The Arts and Crafts movement also had an impact on her.

She studied drawing and painting in school, but she quickly became obsessed with photography. Käsebier, like many other art students at the time, decided to travel to Europe to further her education. She began 1894 by studying the chemistry of photography in Germany, where she was also able to leave her daughters with her in-laws in Wiesbaden. She spent the rest of the year in France, studying with American painter

Frank DuMond.

Gertrude Käsebier returned to Brooklyn in 1895. She decided to become a professional photographer in part because her husband had become quite ill and her family's finances were strained. She worked as an assistant to Brooklyn portrait photographer

Samuel H. Lifshey for a year, where she learned how to run a studio and expanded her knowledge of printing techniques. Clearly, by this point, she had a thorough understanding of photography. Only one year later, she exhibited 150 photographs at the

Boston Camera Club, a massive number for a single artist at the time. The same photographs were shown at the

Pratt Institute in February 1897.

The success of these exhibitions led to another in 1897 at the

Photographic Society of Philadelphia. She also gave a talk about her work and encouraged other women to pursue photography as a career, saying,

"I strongly advise women with artistic tastes to pursue a career in the underserved field of modern photography. It appears to be uniquely suited to them, and the few who have entered it have found rewarding and profitable success."

In 1898, Käsebier watched Buffalo Bill's Wild West troupe parade past her Fifth Avenue studio in New York City, toward Madison Square Garden. Her memories of affection and respect for the Lakota people inspired her to send a letter to

William "Buffalo Bill" Cody requesting permission to photograph the members of the Sioux tribe traveling with the show in her studio. Cody and Käsebier were similar in their abiding respect for Native American culture and maintained friendships with the Sioux. Cody quickly approved Käsebier's request and she began her project on Sunday morning, April 14, 1898. Käsebier's project was purely artistic and her images were not made for commercial purposes. They never were used in Buffalo Bill's Wild West program booklets or promotional posters. Käsebier took classic photographs of the Sioux while they were relaxed.

Chief Iron Tail and

Chief Flying Hawk were among Käsebier's most challenging and revealing portraits. Käsebier's photographs are preserved at the National Museum of American History's Photographic History Collection at the Smithsonian Institution.

Red Horn Bull, a Sioux Indian from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, c. 1900, U.S.

Library of Congress © Gertrude Käsebier

Käsebier's session with Iron Tail was her only recorded story:

"Preparing for their visit to Käsebier's photography studio, the Sioux at Buffalo Bill's Wild West Camp met to distribute their finest clothing and accessories to those chosen to be photographed." Käsebier admired their efforts, but desired to, in her own words, photograph a

"real raw Indian, the kind I used to see when I was a child", referring to her early years in Colorado and on the Great Plains. Käsebier selected one Indian,

Iron Tail, to approach for a photograph without regalia.

"He did not object. The resulting photograph was exactly what Käsebier had envisioned: a relaxed, intimate, quiet, and beautiful portrait of the man, devoid of decoration and finery, presenting himself to her and the camera without barriers." Several days later, Chief Iron Tail was given the photograph and he immediately tore it up, stating that it was too dark. Käsebier photographed him again, this time in his full regalia. Iron Tail was an international celebrity. He appeared with his fine regalia as the lead with Buffalo Bill at the Avenue des Champs-Élysées in Paris, France, and the Colosseum of Rome. Iron Tail was a superb showman and disliked the photograph of him relaxed, but Käsebier chose it as the frontispiece for an article in the 1901

Everybody's Magazine. Käsebier believed all the portraits were a

"revelation of Indian character", showing the strength and individual character of the Native Americans in

"new phases for the Sioux".

In her photograph of Chief Flying Hawk, his glare is the most startling image among those portraits by Käsebier, quite contrary to the others who were shown as relaxed, smiling, or making a

"noble pose". Flying Hawk was a combatant in nearly all of the fights with United States troops during the Great Sioux War of 1876. He fought along with his cousin

Crazy Horse and his brothers,

Kicking Bear and

Black Fox II, in the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876. He was present at the death of Crazy Horse in 1877 and the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890. In 1898, when the portrait was taken, Flying Hawk was new to show business and he was unable to hide his anger and frustration about having to imitate battle scenes from the Great Plains Wars for Buffalo Bill's Wild West in order to escape the constraints and poverty of the Indian reservation. Soon, Flying Hawk learned to appreciate the benefits of a Show Indian with Buffalo Bill's Wild West. Flying Hawk regularly circulated show grounds in full regalia and sold his

"cast card" picture postcards for a penny to promote the show and to supplement his meager income. After the death of Iron Tail on May 28, 1916, Flying Hawk was chosen as his successor by all of the braves of Buffalo Bill's Wild West and he led the gala processions as the head Chief of the Indians.

I am now a mother and a grandmother, and I do not recall that I have ever ignored the claims of the nomadic button and the ceaseless call for sympathy, and the greatest demand on time and patience. My children and their children have been my closest thought, but from the first days of dawning individuality, I have longed unceasingly to make pictures of people... to make likenesses that are biographies, to bring out in each photograph the essential temperament that is called, soul, humanity. -- Gertrude Käsebier

Over the next decade, she took dozens of photographs of the Indians in the show. Some of those photographs become her most famous images. Unlike

Edward Curtis, a photographer who was her contemporary, Käsebier focused more on the expression and individuality of the person than their costumes and customs. While Curtis is known to have added elements to his photographs to emphasize his personal vision, Käsebier did the opposite, sometimes removing genuine ceremonial articles from a sitter to concentrate on the face or stature of the person.

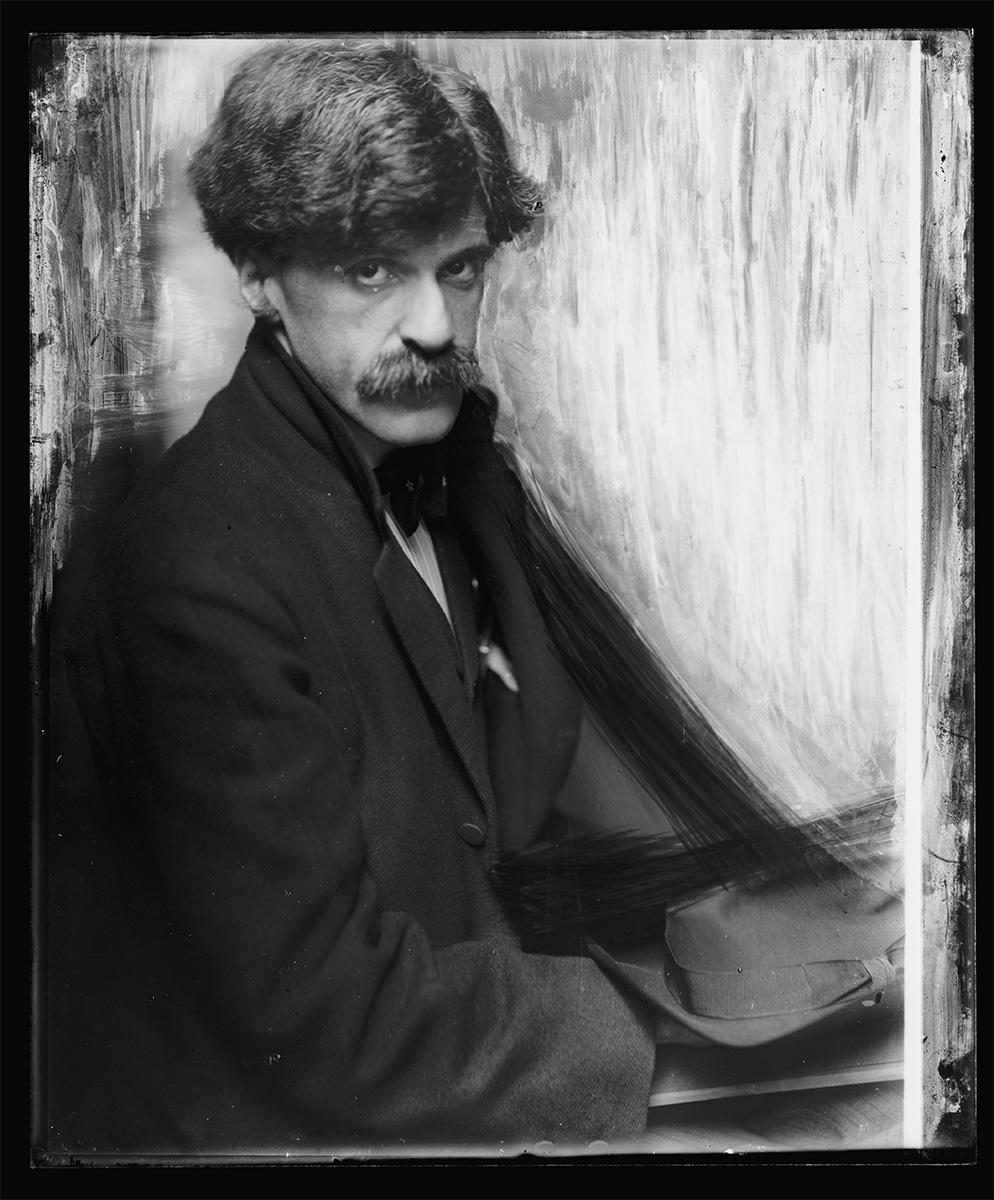

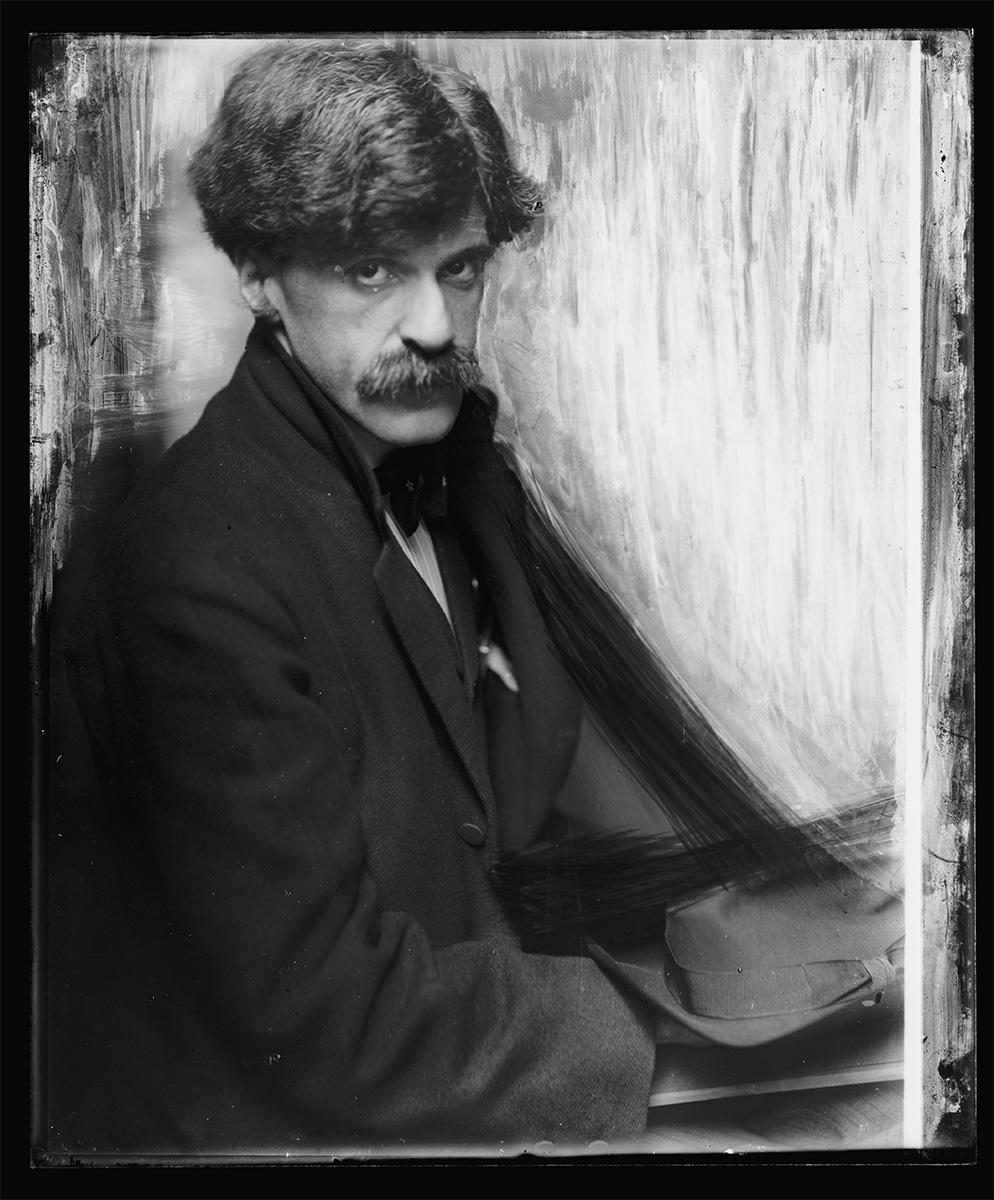

In July 1899,

Alfred Stieglitz published five of Käsebier's photographs in

Camera Notes, declaring her

"beyond dispute, the leading artistic portrait photographer of the day". Her rapid rise to fame was noted by photographer and critic

Joseph Keiley, who wrote

"a year ago Käsebier's name was practically unknown in the photographic world... Today that names stands first and unrivaled...". That same year her print of

The Manger sold for $100, the most ever paid for a photograph at that time.

In 1900, Käsebier continued to gather accolades and professional praise. In the catalog for the Newark (Ohio) Photography Salon, she was called

"the foremost professional photographer in the United States". In recognition of her artistic accomplishments and her stature, later that year, Käsebier was one of the first two women elected to Britain's Linked Ring (the other was British pictorialist Carine Cadby).

The next year,

Charles H. Caffin published his landmark book Photography as a Fine Art and devoted an entire chapter to the work of Käsebier ("Gertrude Käsebier and the Artistic Commercial Portrait"). Due to demand for her artistic opinions in Europe, Käsebier spent most of the year in Britain and France visiting with

F. Holland Day and

Edward Steichen.

Alfred Stieglitz, c. 1902, U.S.

Library of Congress © Gertrude Käsebier

In 1902, Stieglitz included Käsebier as a founding member of the Photo-Secession. The following year, Stieglitz published six of her images in the first issue of Camera Work. They were accompanied by highly complementary articles by Charles Caffin and Frances Benjamin Johnston. In 1905 six more of her images were published in Camera Work, and the following year, Stieglitz presented an exhibition of Käsebier photographs (along with those of Clarence H. White) at his Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession.

The strain of balancing her professional life with her personal one began to take a toll on Käsebier at this time. The stress was exacerbated by her husband's decision to move to Oceanside, Long Island, which had the effect of distancing her from the New York artistic center. In response, she returned to Europe where, through connections provided by Steichen, she was able to photograph the reclusive

Auguste Rodin.

When Käsebier returned to New York an unexpected conflict with Stieglitz developed. Käsebier's strong interest in the commercial side of photography, driven by her need to support her husband and family, was directly at odds with Stieglitz's idealistic and antimaterialistic nature. The more Käsebier enjoyed commercial success, the more Stieglitz felt she was going against what he felt a true artist should emulate. In May 1906, Käsebier joined the Professional Photographers of New York, a newly formed organization that Stieglitz saw as standing for everything he disliked: commercialism and the selling of photographs commercially rather than for love of the art. After this, he began distancing himself from Käsebier. Their relationship never regained its previous status of mutual artistic admiration.

Eduard Käsebier died in 1910, finally leaving his wife free to pursue her interests as she saw fit. She continued to follow a separate course from that of Stieglitz and helped to establish the Women's Professional Photographers Association of America. In turn, Stieglitz began to publicly speak against her contemporary work, although he still thought enough of her earlier images to include 22 of them in the landmark exhibition of pictorialists at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery later that year.

The next year, Käsebier was shocked by a highly critical attack made by her former admirer,

Joseph T. Keiley, that was published in Stieglitz's Camera Work. Why Keiley suddenly changed his opinion of her is unknown, but Käsebier suspected that Stieglitz had put him up to it.

Part of Käsebier's alienation from Stieglitz was due to his stubborn resistance to the idea of gaining financial success from artistic photography. If he felt a buyer truly appreciated the art, he often sold original prints by Käsebier and others at far less than their market value and, when he did sell prints, he took many months before paying the photographer of the work. After several years of protesting these practices, in 1912, Käsebier became the first member to resign from the

Photo-Secession.

In 1916, Käsebier helped

Clarence H. White found the group Pictorial Photographers of America, which was seen by Stieglitz as a direct challenge to his artistic leadership. By this time, however, Stieglitz's tactics had offended many of his former friends, including

White and Robert Demachy, and a year later, he was forced to disband the Photo-Secession.

During this time, many young women starting out in photography sought out Käsebier, both for her photographic artistry and for inspiration as an independent woman. Among those who were inspired by Käsebier and who went on to have successful careers of their own were

Clara Sipprell,

Consuelo Kanaga,

Laura Gilpin,

Florence Maynard, and

Imogen Cunningham.

Throughout the late 1910s and most of the 1920s, Käsebier continued to expand her portrait business, taking photographs of many important people of the time, including

Robert Henri,

John Sloan,

William Glackens,

Arthur B. Davies,

Mabel Dodge, and

Stanford White. In 1924, her daughter, Hermine Turner, joined her in her portrait business.

In 1929, Käsebier gave up photography altogether and liquidated the contents of her studio. That same year, she was given a major solo exhibition at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences. Käsebier died on October 12, 1934, at the home of her daughter, Hermine Turner. A major collection of her work is held by the University of Delaware. In 1979 Käsebier was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.

Source: Wikipedia